Stories

Smith & Caughey's

1880-

When Smith and Caughey’s set up shop on Queen Street, it was virtually business by the yard. That this department store is still with us today is testament to its ability to adapt to a continually changing clothing world. Of all the early Auckland department stores, or draperies as they were initially known, it is the sole survivor, Milne & Choyce, John Courts, George Courts and Rendells having long since closed their doors.

Smith’s Cheap Drapery Warehouse was established in Upper Queen Street in 1880 by Irish immigrant Marianne Smith. As her business prospered, she was joined by her husband William Smith and a year later by her brother Andrew Caughey. In 1882 the business became Smith & Caughey, Drapers and Clothiers and, in 1884, moved to its present Queen Street location.

Marianne Caughey Smith-Preston (1851–1938) was a philanthropist as well as a businesswoman. In 1935 she was awarded an MBE.

The demand for fabric grew out of necessity as the new colonists of all classes had to be clothed. As there were no ready-made garments available, the only option was to sew their own or, if they could afford it, hire a dressmaker to do it for them. Seamstresses, milliners and tailors featured high on the list of preferred immigrants.

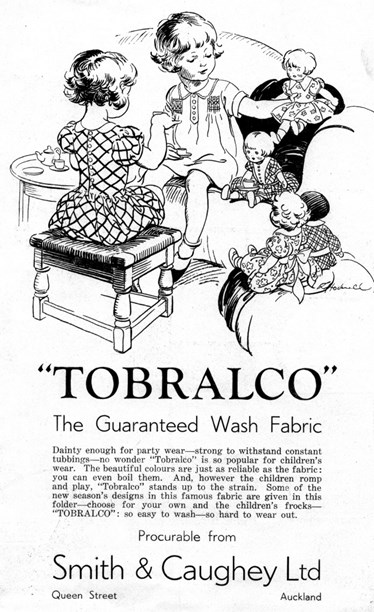

From the outset, the store focused on the sale of fabrics which it sourced, via its London buying office, from leading textile houses in Britain and Europe. These included, over the years, Courtaulds, Moygashel, Horrockses, Liberty’s and Tootal whose Tobralco cottons were popular for childrenswear.

Tobralco fabric sample leaflet, 1932. Image courtesy of Smith & Caughey's.

From Cottons to Silks to Woollens, Smith & Caughey’s catered to every wardrobe need. In an advertisement in the Auckland Star in 1898, inspection was invited of '100 exclusive dress lengths of new black fabrics'. The emphasis on black dress fabrics can be attributed to the tradition of widows wearing black for a two-year mourning period and women in general dressing in black for funerals. Reg Lord, who began working in Silks in 1908, recalled a fellow employee reading the death notices in the newspaper and mailing samples of black cloth to the bereaved.

Tarantulle lingerie fabric advertisement, Smith & Caughey’s catalogue, 1919.

Smith & Caughey’s naturally lit Dress Department, later renamed the Fabric Hall, eventually became one of the largest in Australasia. Despite competition from household effects, soft furnishings, china, toiletries, fashion accessories and, from the late 1800s, off-the-peg clothing, the fabric department had the highest turnover in the store for almost a century.

Smith & Caughey’s Fabric Department, 1923.

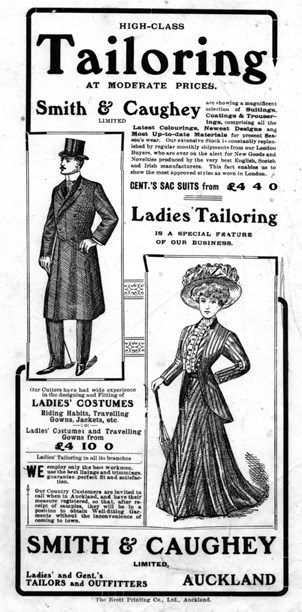

The advent of ready-to-wear, described as ready-to-put-on clothing, did nothing to diminish the demand for fabrics. Garment sizing was limited, so unless one was a stock size, the skills of a competent tailor or dressmaker (amateur or professional) were still required. By the early 1900s, Smith & Caughey’s were advertising: 'High class tailoring at modest prices. Our cutters have wide experience in the design and fitting of Ladies Costumes - riding habits, travelling gowns, jackets, dinner and evening gowns. We employ the best workmen, use the best linings and trimmings and guarantee perfect fit and satisfaction'.

Smith & Caughey’s tailoring advertisement, early 1900s.

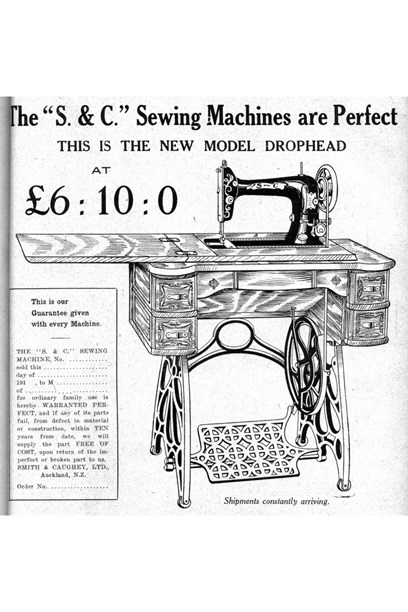

Using fabrics selected from the Dress Department, garments were made-to-measure in the store’s own workrooms. The same sewing machines used in the workrooms, American imports considered 'the best that could be purchased' were also available for sale. As the tailors were often men, the private fitting rooms had a lady assistant to attend to customers.

The S & C Drophead Sewing Machine, Autumn/Winter catalogue, 1910.

Country customers were advised to call in when visiting Auckland to have their 'measure registered'. For those unable to do so, self-measurement charts were included in the store’s seasonal catalogues. The sketches of the figures in the self-measurement charts were based on the fashion silhouette and clothing current at the time. The androgynous body shape of the 1920s bore no resemblance to the S-bend silhouette of 1906.

Smith & Caughey’s self-measurement chart.

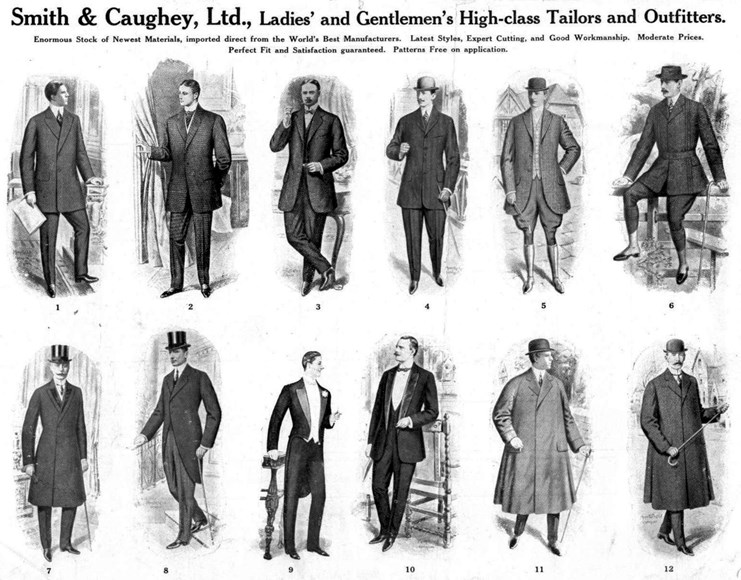

Smith & Caughey’s also made-to-measure for men. A 1906 advertisement promising 'expert cutting and good workmanship' featured suits, riding habits, overcoats, Norfolk jackets, cutaway coats, dinner-suits and white tie. Customers were offered a choice of ‘the latest suitings, coatings and trouserings, constantly replenished by regular monthly shipments from London’. The proffered outfits confirm that colonial ‘gentlemen’ continued to favour the English style of dress, observing the same formalities as they would have done at ‘Home’ (migrant-speak for England).

Men’s tailoring advertisement, Smith & Caughey’s catalogue, 1906.

It was estimated in an article in the Auckland Star in 1898 that women of modest means would buy up to four hats a season, wealthy women ten or more. Smith & Caughey’s kept pace with the demand by importing hats from Paris and London and making model hats in their own millinery workrooms. For women who wished to decorate their hats themselves, they provided all the trimmings – feathers, jewelled hat-pins, artificial flowers and veiling which, in 1916, comprised 'Russian, Chenille Spot, Shadow, Fancy and Plain Nets in Black and White and all good colours.' Flower-lovers were offered a choice of 'rose droops, lily trails and poppy clumps'.

In 1903, Smith & Caughey’s won 'The Monster Good Taste Competition of Australasia, organised by the Australian monthly magazine New Idea, and judged by the magazine’s readers. The winning garment, a lace-trimmed walking costume with a flounced hem, generated a lot of publicity, helping to consolidate the store’s reputation as a fashion leader.

Smith & Caughey’s winning entry in the Monster Good Taste Competition of Australasia. New Zealand Graphic, 1903.

The availability, better sizing and affordability of ready-made clothing led to the eventual closure of Smith & Caughey’s workrooms. The focus shifted from custom-made to quality pre-made garments. By sending its buyers to Britain and Europe on a regular basis, and with benefit of its overseas buying offices, the store retained its position as a fashion arbiter, tempting its customers with 'the choicest models and up-to-date designs'.

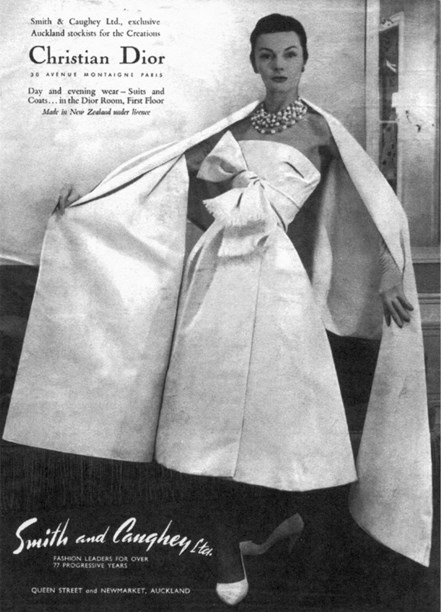

And so it went, decade after decade – Blouse Costumes in 1906, Visiting Frocks in 1916, Afternoon Dresses in 1925, bias-cut satin Evening Gowns in the 1930s, Tailored Suits in the war-torn Forties and, in the 1950s, Dior’s New Look, courtesy of El Jay’s Gus Fisher who made the French couturier’s designs in New Zealand under licence.

Smith & Caughey’s Christian Dior advertisement. Vogue New Zealand, 1957.

Import restrictions, imposed in 1938 and not lifted until 1982, curtailed the amount of clothing that could be brought in from overseas. Throughout this period, Smith & Caughey’s sold predominantly local labels. In the 1960s and 1970s, in a bid to attract younger customers, these included Peppertree, Society, Miss Deb and Thornton Hall.

The Fabric Hall was less affected by import licensing than some of the other departments. It continued to be well-stocked, and home-sewers were not the only beneficiaries. When a shipment of fabric arrived in-store, fashion designers and clothing manufacturers with no import licences themselves, would turn up, eager to buy in bulk.

As the number of home-sewers decreased, the demand for dress fabrics waned. The Fabric Hall, once the mainstay of the business, closed for good in 2004. While acknowledging the inevitability of the closure, a spokesman for the company expressed the view that it had possibly been delayed a little longer than it should have, for sentimental reasons.

Window display, Smith & Caughey’s Queen Street, Auckland, 2015.

By embracing change and reinventing themselves, as similarly iconic department stores have done overseas, Smith & Caughey’s have withstood competition from fashion boutiques, shopping malls, chain stores and cheap overseas imports. The business maintains a strong fashion presence and is still owned and administered by the Caughey family. The flagship store in Queen Street is complemented by a second store in Newmarket, a fashionable shopping Mecca not far from the CBD.

Text by Cecilie Geary author of Smith & Caughey’s: Celebrating 125 Years 1880–2005. Banner image of the store's Queen Street frontage in 1906, courtesy of Smith & Caughey's.

Last published December 2016.