Stories

Flounces & Frills

Frills denote sweetness and innocence, but they can also spell rusticity, theatricality or femme fatale. Like the colour black, the frill has many sides to its personality. Kevin Berkahn, who made thousands of frills during his 50-year career as a bridal and eveningwear designer, believes the frill, while never really being in fashion, is never out of fashion either.

A look back in time reveals that, with the exception of the mid to late 1920s when the frill-less flapper look prevailed, generations of New Zealand fashion designers and dressmakers have embraced the frill as a form of decoration.

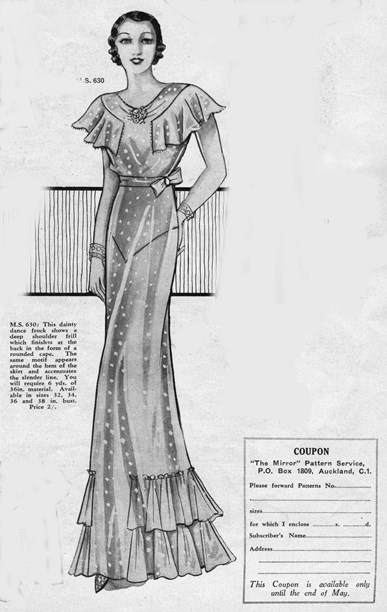

‘Dainty dance frock’ pattern. The Mirror magazine, May 1934.

Frilly finery has long been associated with weddings. With limited ready-to-wear choices, New Zealand brides in the early 19th century went to professional dressmakers to have their gowns made. Larger department stores also offered dressmaking services. Gowns from this period were very detailed and layers of soft frills were often integral to the design. Auckland couturier Colin Cole later created wedding dresses on similar lines but with a modern sensibility.

Frilled skirts feature on a wedding gown, custom-made by the Dunedin department store DSA for Tui McKinnon in 1920, and on 1960s’ bridalwear by Colin Cole.

In the 1960s, a neo-romantic look with bride-appeal emerged from swinging London. Redolent of never-ending English Edwardian summers and tea on the lawn, it featured long demure dresses in soft fabrics such as cotton, organdy and voile. Gone were the frothy frills and, in their place, tucks, discreet ruffles and delicate lace edgings. Small posies replaced the elaborate wedding bouquet and big-brimmed hats or bonnets were worn instead of a veil. This look has been revisited many times over the years by New Zealand designers, although not necessarily for weddings.

The Romantic Look, as portrayed in 1968 by Babs Radon (organza wedding dress) and Miss Deb (sheer polyester party dress with pleated skirt).

Decollete necklines and voluminous tulle skirts defined the 1950s/early 1960s ballgown. The top of the bodice, either strappy or strapless, was often edged with tiers of tiny fanned-out frills. A preference for pastel colours and hemline ruffles added to the fairy-tale princess effect.

Frills were also used to enhance evening dresses cut on slimmer lines. In 1963, Peggie Wilson brought her frill skills into play and became third runner-up in the Gown of the Year contest. Her dress, a slender column of dusky pink pleated frills, was caught in at the waist with a crystal-beaded sash.

Peggie Wilson called this dress, which won third place in the 1963 Gown of the Year, Vienna Bon Bon. It was made from a new synthetic fabric developed by hosiery company Prestige.

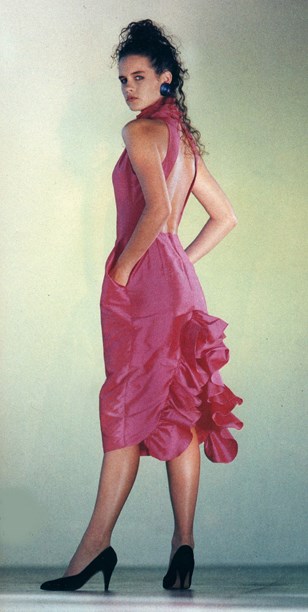

No stranger to frills since her comeback in the 1990s, Trelise Cooper displayed a predilection for flouncy trims when she started her first label Limited Editions in the previous decade. Rather than girly frills, these were conspicuous ruffles, a celebration of 1980s ostentation and glamour.

Fuchsia silk cocktail dress by Trelise Cooper for Limited Editions. ChaCha, December 1986. Photo by Kerry Brown.

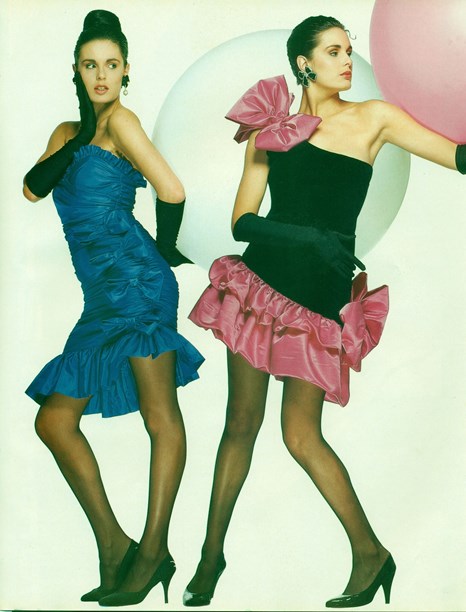

Made mainly from rich fabrics such as taffeta and satin, ruffles in the 1980s grew bigger and bigger. They were at their most flamboyant on party dresses and clubwear. Ruching and out-size bows became fashionable at the same time and frequently appeared with ruffles on the one garment. Colours equalled the size of the ruffle in boldness, shocking pink being a particular favourite.

Velvet and satin dress by Barbara Lee (right) and taffeta dress by Mr K for Pumperdink (left). Fashion Quarterly, Autumn 1988.

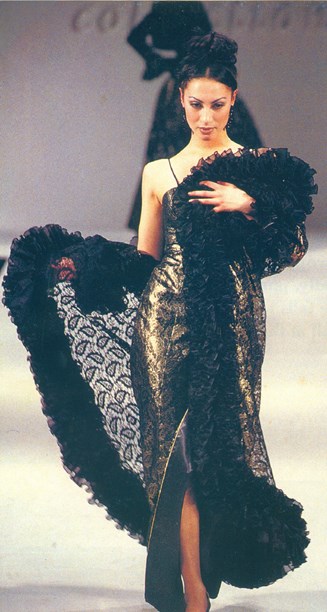

From a seamstress who had worked for Chanel in Paris, Ches Pritchard learned the golden rule of frill-making. To sit properly and for a fuller flounce, a frill must be cut on the bias. For the evening gowns he showed in the early Corbans Fashion Collections, he devised a number of ways to achieve the looks he wanted. "Eveningwear in the 1980s and early 90s was very sexy," he says, "and overblown frills were part of the seduction." Ches ran taffeta ruffles vertically or diagonally down form-fitting dresses to emphasise the hips, filled deep v-necklines with frills to bring in volume, and gave tulle dresses more weight by adding deep satin ruffles at the hem. The tightly gathered double frills with which he edged a sheer black evening coat, worn over a gold evening dress on the Corbans catwalk, fluffed out to give the illusion of a feather boa.

Ches Pritchard sheer evening coat with ruffles. Corbans Fashion Collections, 1992.

Colin Cole, Kevin Berkahn, Vinka Lucas, Barbara Lee and Patrick Steel were other designers who worked the frill to the max. In the 1982 Benson & Hedges Fashion Design Awards, Patrick won the prize for Most Outstanding Evening Garment. His entry, a body-defining, jet-sequinned dress rising from a cloud of white frills, was complemented by a ruffled cloak of crystal organza.

Patrick Steel’s Outstanding Evening Garment award winner, Benson & Hedges Fashion Design Awards, 1982.

For the finale of his debut fashion collection at the Auckland War Memorial Museum in 1985, Patrick Steel sent out the ultimate frou-frou bride. Swathed about the shoulders with flouncy lace frills, the ruched pink satin dress billowed out below the hip in torrents of tulle. The bride’s bouffant tulle wig was inspired by the massive wigs worn in the 1984 movie, Amadeus. This was a fashion statement that wouldn’t have looked out of place in Camp: Notes on Fashion, the costume exhibition that opened in May 2019 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Peasant-style dressing, derived from an amalgam of pastoral pasts, which British designer Laura Ashley helped spearhead in the 1960s, offers another perspective on the frill. Variously interpreted as the peasant/gypsy/bohemian look, it crops up anew every few years. Key to this look are camisole tops, off-the-shoulder blouses, eyelet embroidery, floral prints and multi-layered skirts formed from rows of ruffles.

Thornton Hall broderie anglaise dress with hook and eye fastening. Summer collection, 1987.

By their very nature, frills fit the brief for anything girlish. They lend a flirtatious air to sunfrocks, playsuits, summer separates, even swimwear. Frills aren’t seen much on swimsuits these days, but before the introduction of Lycra and the endless possibilities it provided, swimsuits were a lot fussier. In the 1950s, one-piece suits, ruffled across the hip-line, were very popular.

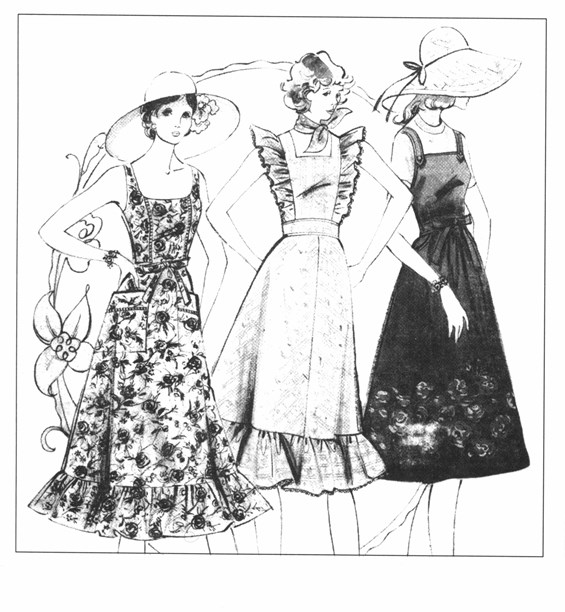

Smith & Caughey advertisement for Miss Deb Spring Blossoms sunfrocks. Auckland Star, August 1975.

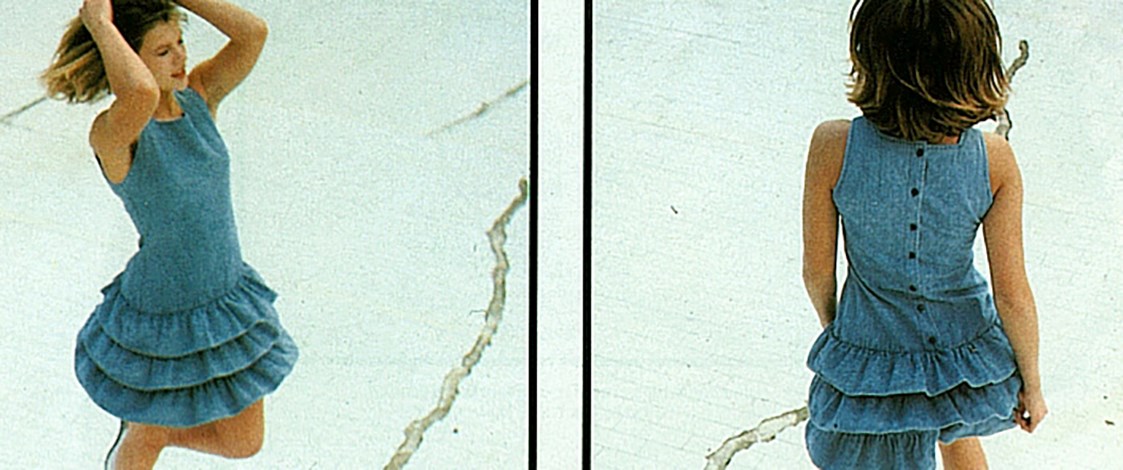

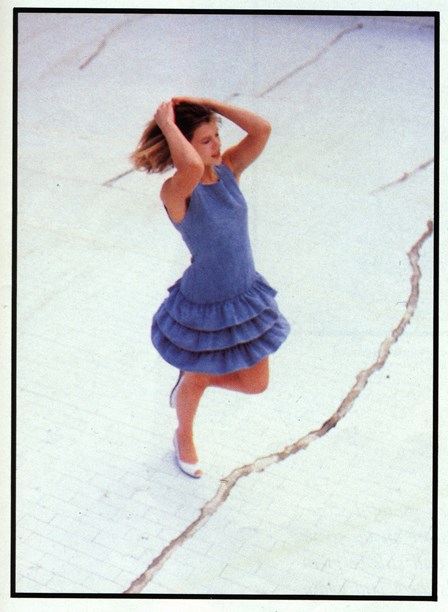

Robyn Hall of High Society Fashions remembers the chambray and denim dresses with short frilly skirts that the company made under its Queens label in the 1980s. "It was a look we picked up from the New York designer Norma Kamali who was one of our favourite muses at the time."

Blue denim ruffle dress by Queens. ChaCha, December 1986. Photo by Derek Henderson.

Norma Kamali is perhaps best known for her sweat-shirting separates, the most famous of which was the rah-rah skirt, a ruffled pull-on mini similar to those worn by American cheerleaders. Derivative of the rah-rah skirt, short dresses with double or triple ruffled hems enjoyed a long run in New Zealand in the 80s. They were produced mainly by street-fashion designers or manufacturers such as High Society who catered for the mass market.

Modern-day frill-seekers, keen to do their bit for the planet by recycling, are searching out vintage pieces and altering them to suit, thus giving them a second life. As elaborately frilled garments were generally designed for special occasions, they were possibly only worn a few times and are likely to still be in good condition.

Pictured here in 1982, the white Chique by Marnella dress (left) was purchased on TradeMe for $50 by Fiona Ralph in 2017. It had been shortened at some stage so she replaced the missing ruffles and removed the sleeves. She wore the revamped dress when she married CP Moore in Nelson the same year.

An advocate for the frill and for ethical fashion made from sustainable materials, Maggie Marilyn’s Maggie Hewitt has turned the frill into a work of art. Adroitly placed on skirts, shirts, dresses and jackets, ruffles and frills are an important part of her design aesthetic.

The frilled dress according to Maggie Marilyn. Images from 2019 and 2018 look-books.

For what amounts to little more than a gathered strip of cloth, the frill’s transformative powers are indisputable. A frill here, a flounce there, and even the simplest garment begins to sing.

Text by Cecilie Geary.

Published June 2019.