Stories

Bruce Papas

1931-2020

The man who became New Zealand's first fashion apprentice was training to be a cabinet maker when a life-changing job offer landed at his feet.

Stephanos Bruce Papas grew up in a family of seven children in Auckland. His name reflects his heritage: Stephanos was a 'noble name' chosen by his Greek grandmother, and his Scottish family requested the name Bruce.

To the disapproval of his Greek family, Bruce began to be known by his second name as a child. "Sadly Stephanos was too foreign." Throughout his career, Bruce worked under variations of his name including Bruce Papas, Bruce Papos and Staevro Boutique.

Bruce was not interested in a career in fashion when he was growing up, although he was often called on to help design and sew his sisters' ball gowns. He was "good with his hands" and pursued many creative hobbies including hand painting glass. He was training as a cabinet maker at Seddon Memorial Technical College in Auckland when the fashion designer Flora MacKenzie came across an example of his glass work. She offered the 15-year-old a job in her salon, Ninette Gowns.

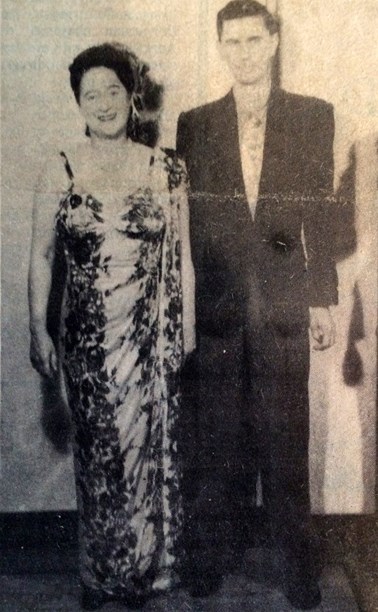

Bruce Papas and Flora MacKenzie at a ball. Bruce designed Flora's dress.

His parents were concerned that the fashion design industry wasn't a stable career choice but they agreed on the condition that he had a formal apprenticeship. Flora's lawyers had to draw up a contract as there was no such thing at the time as a formal apprenticeship in design. Bruce was initially employed to design embroidery for the gowns in the salon. He joined a staff of about ten – including four machinists, a cutter/presser, a hand sewer and a beading specialist. "It was pretty overwhelming as I was just a kid and I didn't know anything about embroidery." However, he thought it was all "rather wonderful" and decided to learn the trade in its entirety. He began by enrolling in a night class to learn tailoring.

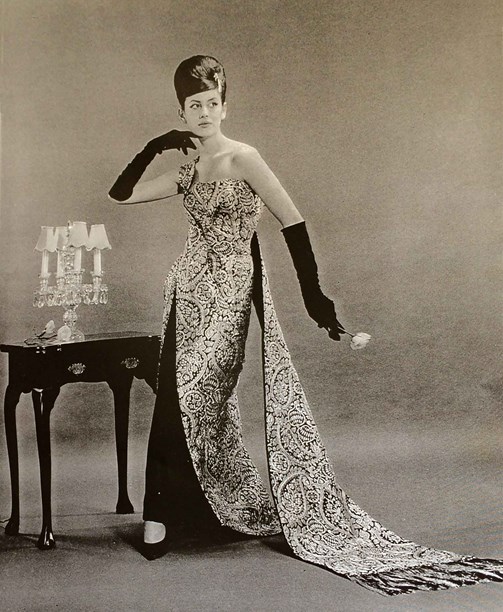

Bruce Papas designed this gown while he was completing his apprenticeship at Ninette Gowns. Image from Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira, 2018.11.1. All rights reserved.

Ninette Gowns occupied the 4th floor of a building on the corner of Queen Street and Vulcan Lane. The fitting room, decorated in a 'Black Chinese Banquet' theme, featured large mirrors, furniture embossed with mother of pearl, alabaster lamps and black velvet hangings that were heavily embroidered in gold dragons. The 'Jade' room was furnished with a jade-coloured carpet. Bruce describes it a "truly wonderful environment to inspire".

During his five-year apprenticeship, Bruce learnt about fabrics, design, drafting, pattern making, hand cording and embroidery. But after the sudden death of his father, Bruce decided to leave Ninette Gowns. He set up a workroom and fitting rooms in his mother's house. His new business, Staevro Gowns, was named after his father. Bruce continued to specialise in haute couture for a small number of clients, some of whom followed him from Ninette Gowns. His wedding and bridesmaids gowns, in particular, received much acclaim.

Bruce Papas with his sister Dawn on her wedding day in 1952. He designed and made her embossed satin brocade wedding dress. Image © Bruce Papas.

However, he was soon called up for compulsory training with the RAF. Bruce wasn't concerned about the interruption to his career. "Training ... gives you an inner strength," he said in a 1991 interview with Raewyn Patchett.

In 1956, Bruce shifted his practice in a new direction after he was approached by the Auckland department store Milne & Choyce. They were looking for a full-time designer to create original designs for their shops. The seasonal range of one-off model garments would be labelled 'Bruce Papos designer for Milne and Choyce', and Bruce was also to design for their eponymous in-house label, as the head of their fashion team. The different spelling of his name was perhaps chosen to better capture how his name should be pronounced in the New Zealand vernacular of the time.

Bruce designed for Milne & Choyce under the name Papos.

The Bruce Papos collection was presented in the windows of Milne & Choyce in Queen Street. The window displays required months of planning. "If the theme colour for spring/summer was apricot and alabaster, then the whole windows would be done in that." Milne & Choyce’s seasonal window displays would draw crowds from all over Auckland. "They used traffic control to move the people along," Bruce recalls.

In 1961, Bruce won the inaugural Golden Shears Awards with a gown that he called 'Golden Peacock'. This is the gown that Bruce is most proud of, an elegant garment that he made from only one small piece of rather expensive fabric. It cost £81, an astounding amount, considering most model gowns of the time sold for £30.

In 1961 Bruce Papas won the inaugural Golden Shears Awards with his gown, 'Golden Peacock'.

Fabric always remained the starting point for Bruce’s designs. "I always began with the fabric. I had an idea in my head about the fabric and I would put it down on paper, throw the fabric on the model and then work out my design and pattern."

He left Milne & Choyce in 1965 to open Bruce Papas Salon in the Kerridge Odeon retail development, 246, on Queen Street. Many of his clients followed, keeping him and his staff of five extremely busy. Bruce frequently employed artists and specialists to create materials for his gowns. Weaver Zena Abbott was one of many artists who made fabrics for Bruce. He created one-off designs and successfully brought a craft element to high fashion.

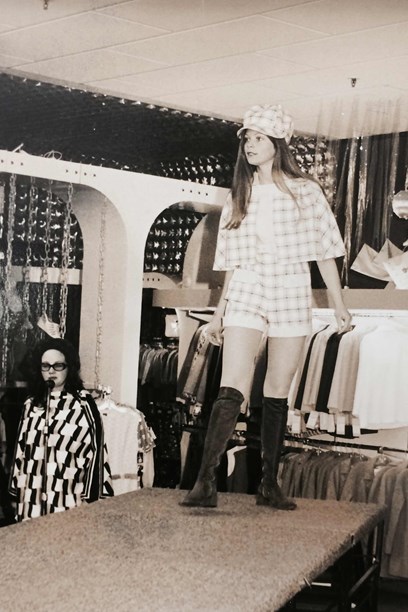

But the long hours took their toll and Bruce collapsed after having a stroke. He recuperated in his home in Titirangi where he learnt to work with clay to help with his recovery. From there he went to work for Robertson Manufacturing Company and the Lady Jet label. This was an unexpected turn as Robertson’s manufactured clothing was extremely different from Bruce’s one-off designs. But it turned out to be successful – bringing the haute couture look into mass produced clothing. "It showed that you really had to be versatile, to be able to create not only for the sophisticated but for the young at heart and the young."

Bruce's designs for the Lady Jet label brought the haute couture look into mass produced clothing.

Bruce designed for the Lady Jet label for six years until the owner passed away. He continued one-off work for his private clients under the Bruce Papas Model label until the early 1990s, before retiring from textiles to focus on creating richly-detailed work with clay.

Text by Kelly Dix. Banner image of Bruce Papas in the Milne & Choyce workroom, 1956.

Last published June 2014, updated March 2020.