Stories

Bridal White

"The bride", noted the NZ Graphic and Ladies Journal in June 1890, "wore a very tasteful but unassuming costume of soft white silk with side panels and folds on the bodice, the dress being made with a train; a handsome Honiton lace veil fell over all, being fastened to her hair by a lovely pearl spray, a gift of the bridegroom. She carried a lovely bouquet with long streamers."

By the 1890s, society journalism was on the rise. Newspapers and women’s periodicals such as the Graphic covered weddings on a regular basis, detailing not just what the bridal party wore but female guests as well. The short-lived Weekly Graphic and NZ Mail newspaper (1908-1913) called its wedding page 'Orange Blossoms', a reference to a symbolic bridal flower.

Hunter Blair-Rhodes bridal party, NZ Graphic, 1893. NZG 18931111-398-1, Auckland Public Library Heritage Collection.

Why White?

The practice of wearing white for weddings wasn’t adopted until the mid-18th century and then only because it conveyed to the world at large that the bride’s family was wealthy enough to afford a dress that would be worn only once. Not until Queen Victoria’s marriage to Prince Albert in 1840 did white become the norm. It was also during her reign that the virginal connotation of white for brides arose.

New Zealand colonists adhered to the white bridal tradition as they did to other British customs. After the sewing-machine was invented in the mid-19th century, home dressmakers came into their own. Wedding dresses were often sewn by the bride, her mother or her sisters. Richer folk employed professional dressmakers to make their gowns or engaged the services of department stores with dressmaking facilities.

Silk and lace wedding gown made by Mary Gillieson Paterson, with the assistance of her mother, for her marriage in Kaihiku, South Otago in 1905. 2006/94/1. Courtesy Toitū Otago Settlers Museum.

Wedding gowns seldom diverged from the prevailing fashion of the day. They were marked out from everyday clothes by the colour white and the relative richness of the fabrics. Rigidly corseted to conform to the hourglass silhouette, brides in the 1890s wore dresses with high necklines, known as 'wedding band' collars, and long bell-shaped skirts with trains. Sleeves grew to enormous proportions and a good deal of silk was worn.

Sketch of ‘A Stylish Wedding Gown’, Auckland Star 1895.

Furbished (a word much used at the time) with flounces and cascades of lace, bridal gowns at the turn of the century were no less elaborate. The amount of time and effort that went into the making of these ornate creations was prodigious.

By tradition, the bridegroom was supposed to choose a flower for his boutonniere (button-hole) that appeared in the bride’s bouquet or head-dress. Circa 1900. Fran McGowan Private Collection.

Less Fuss, Less Frills

At the conclusion of World War One in 1918, simplification had supplanted ostentation. The NZ Observer’s fashion columnist Myra reported a trend for sleeveless tunic dresses distinguished by their lack of trimming. "There is no necessity for a wedding dress to be costly," she wrote. "In these times one often sees a bride looking perfectly charming in a simple muslin or voile frock."

Dresses with long tubular bodices and loosely gathered shorter skirts permitting a glimpse of a silk stockinged leg and dainty shoe were the choice of 1920s brides. Hemlines were often scalloped or asymmetrical and head-dresses, held in place with circlets of real or wax flowers, were worn low on the brow in imitation of the cloche hat.

Bouquets in the early 1920s were lavish confections of flowers, greenery and trailing ribbons. Fran McGowan Private Collection.

The 1930s ushered in the era of the regal bride. Lustrous fabrics, white satin, brocade and crepe de chine included, were configured into fluid, fitted gowns cut on slender, almost medieval lines. This style continued, with some modifications, until the late 1940s when it was replaced by less formal, full-skirted dresses in lighter materials, easily adaptable into summer evening gowns.

Made from pleated stiffened tulle, the fan-shaped head-dress worn by this 1930s’ bride is characteristic of the era. Fran McGowan Private Collection.

And The Bride Wore …

The Ladies Mirror (later The Mirror) founded in 1922, followed the earlier periodicals in reporting on society weddings throughout the country. Photographs of the brides posing for the camera in all their finery, provide an invaluable record, not just of the dress styles of the time, but of head adornments, bouquets and veils. Veils were by no means the rule but they were part of the bridal tradition. Varying in length, they were usually made from flimsy materials such as lace or tulle. The veil had its origins in the flammeum, an all-enveloping yellow veil worn by Roman brides to preserve their modesty. It was reinterpreted in its present form in the 19th century with white replacing the original yellow.

Society weddings page from The Mirror, 1933.

Extravagant Gestures

Wedding gowns in the 1950s followed the lines of Christian Dior’s New Look, as did debutante dresses and dresses for formal balls. The look was defined by bouffant skirts, boned bodices and tiny waists. When Vinka Lucas, whose career as a bridalwear designer spanned several decades, married in 1959, her gown reflected not just her personal design aesthetic but the ultra-femininity of the period. Famous for her theatricality and lavish use of fabrics, she constructed a gown of hand-pleated tulle and Chantilly lace, so voluminous it required curtain wire to support it.

Bridalwear designer Vinka Lucas dressed for her own wedding in 1959. Image © Anita Turner.

Maysie Bestall (later Cohen) and Paula Ryan, who worked as a freelance model in her teens, were among those to be photographed in Vinka’s imaginative creations.

Paula Ryan models a Vinka Lucas gown and head-piece. Image courtesy of Anita Turner.

Spectacular white weddings were also the forte of designer Kevin Berkahn. From the 1960s until well into the 2000s, he dressed thousands of brides. His own wedding in 1962 was an all-white affair. For his bride Shirley he designed a white French lace gown with a crystal and pearl-encrusted bodice and for the five bridesmaids and flower-girl, Empire-waisted dresses in white duchesse satin.

Kevin and Shirley Berkahn’s wedding group, Auckland 1962. Image © Kevin Berkahn.

Polyester, nylon and other synthetic fabrics were introduced in the 1950s, providing brides-to-be with a less expensive option. They were known as the 'whiter-than-whites', on account of their whiteness being more vivid than that of natural fibres.

Breaking The Rules

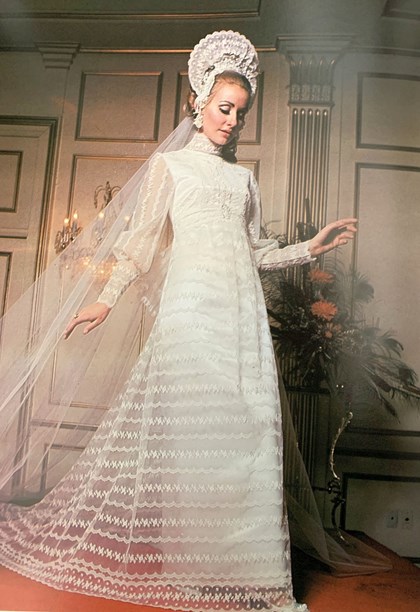

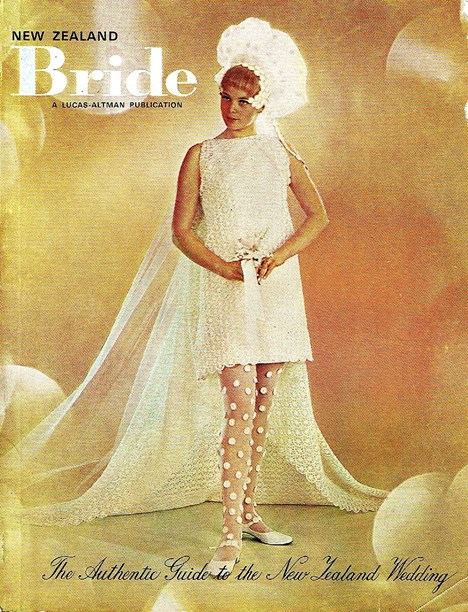

In the 1960s, the young Mod bride exchanged vows in a mini shift dress, lacy tights and low-heeled Mary Jane shoes. Happy to flout dress conventions, she upheld the tradition of wearing white.

Vinka Lucas Italian crocheted lace mini dress modelled by Jo Page and photographed for the cover of New Zealand Bride magazine, a publication founded by Vinka and her husband David in the 1960s. Image © Anita Turner.

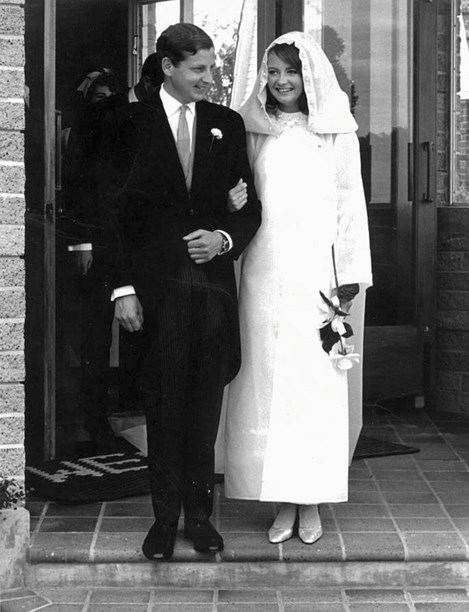

Nostalgia for the Edwardian era, later in the decade, saw a return to romanticism. Demure white dresses, made from fine cotton lawns, organdies and batistes, discreetly trimmed with tucks, lace and narrow frills, conjured up images of a pastoral past which probably only existed in the imagination of painters and poets. Storybook capes and coats with face-framing hoods made a brief appearance at decade’s end.

Typifying the break with tradition, Maysie Bestall chose a hooded coat, which she wore over a Colin Cole dress, for her marriage to Richard Cohen in 1967. Image © Maysie Bestall-Cohen.

While sheath dresses were popular in the 1970s, no one style dominated the decade. The general preference was for long and white, be it a dress, caftan (the hippie influence) or pant-suit, now an accepted form of bridal attire.

The 1970s also saw the emergence of the white-suited bridegroom. For his wedding at Dunedin’s Knox Church in 1970, hairdresser Stuart Ovens wore a white three-piece suit of his own design, made by local tailor Ivan Coward. Channelling John Lennon, of whom Stuart was a fan, the suit comprised a frock-coat with flared sleeves, a waistcoat and high-waisted, flared trousers. A white shirt, white tie, white patent leather shoes and his grandfather’s watch chain completed the outfit. Long white culottes, indistinguishable from a skirt, were worn by the bride.

Here comes the groom. Stuart Ovens at his wedding, Knox Church, Dunedin, 1970. Other white-suited bridegrooms of the period included Maurice Gibb of the Bee Gees (1969) and Mick Jagger (1971). Image © Stuart Ovens.

Romantic Revival

Kevin Berkahn attributed the 1980s’ romantic revival to Princess Diana. Following her wedding to Prince Charles in 1981, he received twelve orders to make exact copies of her Emanuel-designed gown. "Dresses became much grander," he said, "and to get the right look you had to use grand materials". His personal favourites included silk, satin, French lace, "magnificent embroideries". Bridal fabrics previously only 90cm wide were now available in 150cm widths, enabling dresses to be made with fewer seams.

1980s’ wedding gown by Kevin Berkahn features Princess Diana-style puff sleeves and intricate hand-beading.

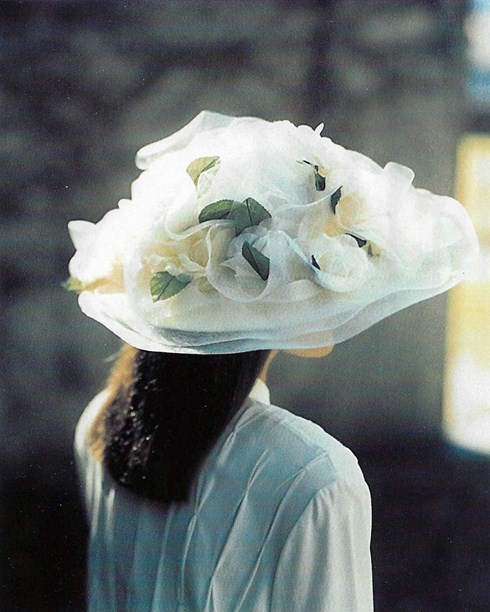

At the same time 80s’ designers were fulfilling the fantasies of those who wanted to look like fairy-tale princesses, other brides were saying "I do" in their mother’s wedding dresses or copies of the original. Yet others were combing vintage clothing shops like Victorian Gilt in Auckland for Edwardian cotton petticoats with lace inserts, hand-made lace camisoles and ribbon-appliqued chemises and nightgowns. Having survived, their pristine whiteness intact, for almost 100 years, these items of intimate apparel were repurposed as outerwear by brides appreciative of the past, and frequently worn with big-brimmed, flower-strewn hats for garden weddings.

Brimmed hat laden with full-blown organza roses. Designed by Pagon Millinery. Fashion Quarterly, late 1980s.

Retro Glamour

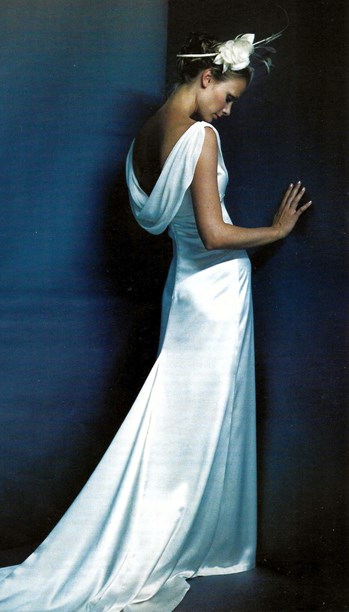

Royal brides were not the only ones to have their gowns copied. Other high profile figures were also a source of inspiration. For her marriage to John Kennedy Jnr in 1996, Carolyn Bessette wore a bias-cut white silk crepe dress reminiscent of a 1930s evening gown. Moulded close to the body and flaring out into graceful ripples at the hem, it had a softly draped neckline dipping to a deep cowl at the back. Variations of this style became popular here, allowing designers with exceptional cutting and construction skills to show them off.

Jane Gower-Hall silk satin gown with silk georgette cowl. Silk and feather headpiece by Liz Mitchell. Fashion Quarterly, Winter 1999.

The Modern Aesthetic

A glance through any of New Zealand’s dedicated bridal magazines today confirms that the notion of white for weddings remains a constant. Be it full-on frou-frou, a satin-lapelled tuxedo, a jumpsuit or a svelte slip-dress devoid of trim, most brides still dream in terms of white. While the idea that a white wedding dress would be worn only once still holds true in some cases, a common trend now is for bridal outfits to lead multiple lives. Another growing trend, among brides keen to do their bit for the planet, is to remake and modernise pre-worn white garments bought online or from recycled clothing boutiques.

Pure silk tent dress from the unreleased Juliette Hogan 2020 Bridal Collection. Photographer: Guy Coombes. Courtesy Juliette Hogan.

Old or new, formal or informal, it’s immaterial. As long as brides wear white, no matter in what shape or form, the continuity of the centuries-old custom is ensured.

Text by Cecilie Geary. Banner photo of an unidentified bride by W H Bartlett, circa 1909. from Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, 1227-75-1.

Published September 2020.