Stories

Wearing Black in Aotearoa

Returning home to New Zealand after a period away, you are immediately aware of the pervasiveness of the colour black in how we dress. It feels strikingly incongruous in a country that thinks of itself as a bright and natural paradise that we choose to clothe ourselves in this dark and colourless hue. Why is wearing black so ubiquitous in New Zealand today and has it always been so? Is it prevalent across all sectors of society; who wears it and what does it signify? Is it a deliberate choice? Does it say something essential about what it means to be a New Zealander?

The most obvious and deliberate appearance of black can be seen in our representative sports uniforms. The black singlet, the black jersey and the black blazer with silver fern emblazoned on its pocket were for many years the constant features of our representative sports uniforms. As sport has become more professional, commerce and technology have aligned themselves with sporting success. The wardrobe of athletes has expanded with warm up clothes, competition gear, formal and informal uniforms all providing increased opportunities for branding. Sports uniforms have become wearable billboards for brand promotion, including 'brand New Zealand', on the international stage.

The New Zealand team for the 1952 Helsinki Olympic Games.

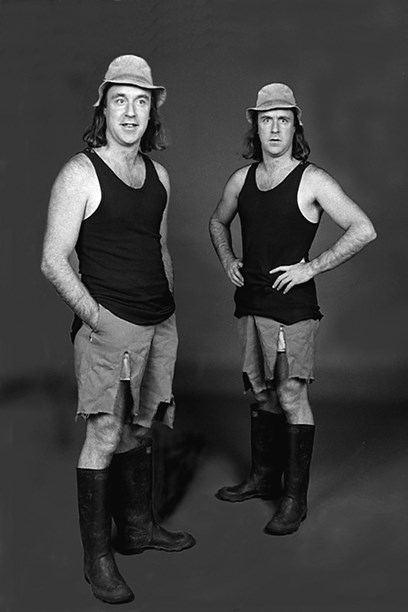

Black also features strongly in some of our most endearing and enduring cultural icons. The black shearing singlet has long functioned as a sort of shorthand for an idealised male New Zealandness. It represents that mythical character, the practical joker who can tackle any task and solve every problem with a piece of number 8 fencing wire. While the black singlet has been around for more than 100 years and continues to do service as a valuable utilitarian garment, its role as a symbol of the quintessential Kiwi bloke is a fairly recent creation popularised by the likes of Barry Crump, Fred Dagg and Billy T James.

'Fred and Fred', 1975. Photo © David Roberts.

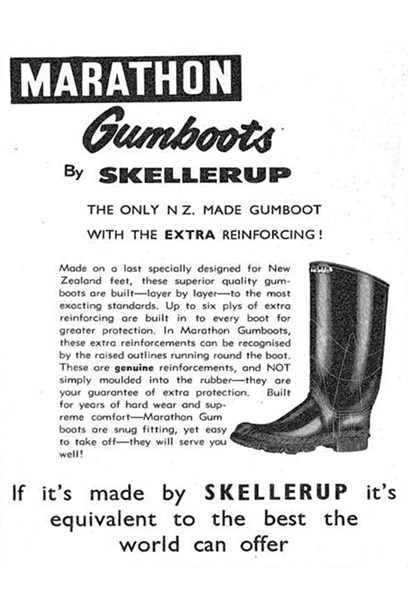

The unsurpassed functionality and practicality of gumboots have guaranteed them a place in every New Zealander’s wardrobe. If today’s tasks are mainly urban they are more likely to be in coloured or patterned plastic but the real labourer’s black rubber gumboots have been made by Skellerup for the past seven decades.

Marathon gumboots by Skellerup were New Zealand's original tall gumboot, first manufactured in the mid 1940s.

Other iconic black wardrobe staples are associated with local heritage brands: Canterbury, a label synonymous with sportswear in New Zealand and for many years the supplier of the All Blacks jerseys, is also the label on a black woollen bathing suit. And the duffle coat, that icon of Dunedin scarfie culture, was manufactured by one of New Zealand’s oldest brands, Hallensteins. All these iconic garments are examples of the use of black for its unassuming and practical qualities.

Figures of authority such as the police, judges and church leaders often dress in black. Here it is not a personal or fashionable choice but rather one of symbolically representing their role in the civil order. Interestingly, those who oppose or position themselves outside the prevailing civil order also often dress in black. Black, therefore, is the marker of both the law and the outlaw. It can be adopted to express and to challenge authority, so Gary Langsford’s European black suits represent his cultural authority as an expert on contemporary art and Tāme Iti’s black suit represents his cultural authority as an activist leader of his Tūhoe people – for both the choice of black is deliberate.

In the local and international music scene there is a lot of black clothing in evidence which marries with our expectations because rock music in all its incarnations is seen, in first instance, as a form of rebellion. But the truth can be somewhat different and the choice of clothing is often determined by motivations other than image. Warmth, practicality, availability are some of the reasons cited and only the most contemporary performers claim to have made a deliberate choice to dress in black in order to promote and enhance their rock credentials.

Black leather jacket belonging to Martin Phillipps of The Chills, black shirt worn by guitarist Jed Town of the post-punk cooperative Fetus Productions and rock 'n' roll star Johnny Devlin wearing a black suit.

Black as a fashionable colour has also been in and out of vogue in New Zealand’s modern history, its status largely a result of fashion influences from abroad. Even though it was a colour of distinction for men, women and children in the Victorian period, it lost favour for the young in the early 20th century where it was only really deemed suitable for married and mature women and all men, of course. However, the modern girl of the 1920s adopted the colour specifically because of its perceived unsuitability. Wearing an unstructured black dress with her newly bobbed hair, she expressed her liberation from the old constraints on women.

The 1920s flapper dresses skimmed rather than hugged the body, representing a new freedom for women. Image © CC BY 4.0 International Licence.

In 1926 Coco Chanel’s little black dress made its first appearance. Epitomising the happy marriage of functionality and style, news of its arrival spread around the world as it slipped seamlessly into our fashion lexicon.

For the mature woman black remained a stylish wardrobe staple over the next decades but in the 1950s it again experienced a fashion moment when it was embraced by the couturiers of Paris for its understated elegance. Christian Dior said, "You can wear black at any time. You can wear it at any age. You may wear it for almost any occasion; a 'little black frock' is essential to a woman's wardrobe."

While New Zealand women were getting their fashion information from a number of international locations at this time, the sartorial influence of Paris was certainly in evidence here too with sophisticated evening and day dresses, such as the black crêpe de chine dress by local label, Fashionbilt.

The late 1950s witnessed a radical shift and black all but disappeared, even for men. Colour and pattern defined the wardrobes of modern Western societies in the optimistic boom time when we embraced consumerism and new labour-saving technologies. Clothing no longer needed to be practical, it could be fun, and black only rarely makes an appearance in the evenings and inevitably in the professional’s business suit.

By the 1970s very little black was seen in mainstream fashion but it was beginning to reassert itself in the margins, with designer boutiques and markets springing up catering to an emerging bohemian culture. Black often lends a base to appliqué and embroidery, such as in this black dress by Annie Bonza, and plain fabrics are customised with tie dying and screen printing.

Black crepe evening dress with satin appliqué and cornelli ribbon by Annie Bonza, 1972.

By the 1980s black returns to the everyday colour palette as an anchor for the exuberant blocks of vibrant hues that defined this era and as a popular choice for eveningwear. While mainstream manufacturing continued to emulate aspirational fashion from abroad, the boutique makers catered to a growing pool of fashion consumers who were seeking something more individual. Both Kevin Berkhan and Patrick Steel provided for the more prosperous of these customers. Through national television coverage, the Benson & Hedges Fashion Awards provided a n accessible public platform for new and emerging designers hoping to gain recognition and a clientèle. For Konstantina Moutos her successes gave her the confidence to open her own salon at the age of 22. For Megan Douglas and Jane Mabee the awards exposure was solicited in support of their existing business.

In 1989 Fashion Quarterly magazine predicted the emergence of a distinctive local style. The removal of industry protection and import restrictions in the later half of the 1980s had caused enormous upheaval to the fashion manufacturing industry and change was inevitable. That change came from the small independent designers who stepped up to replace the progressively defunct mass producers with niche manufacturing. Established labels such as Zambesi and Workshop made the running and were followed by newer players such as Karen Walker and Kate Sylvester.

Ten years after the Fashion Quarterly prediction, that distinctive New Zealand style went to Fashion Weeks in Sydney and then London where it was received with acclaim. This was a pivotal moment not just for our fashion industry but importantly for this story of the colour black.

Designs by Zambesi, NOM*d and WORLD at London Fashion Week, 1999.

The "dark, edgy and intellectual" descriptors that were used by the media in Sydney to praise New Zealand design came to define our fashion style. When the designs of Zambesi, WORLD, NOM*d and Karen Walker, the so called 'New Zealand Four' showed to acclaim in London, it came to also define our view of ourselves. Until now black had been a colour at fashion’s whim, sometimes in and sometimes out; now it was signalled as a defining colour of New Zealandness and gained a place independent of fashion fluctuations and dictates from abroad. The avant garde of designers who showed in London and at Australian Fashion Weeks gave us confidence in our own voice. Emerging designers such as James Dobson and students at the fashion colleges now had role models of international standing in their midst to emulate and respond to.

Garments by Jimmy D with a screenprint by Andrew McLeod, 2010. Photo by Aaron K.

Simultaneously, black was also being adopted by others to define our identity. As the new millennium dawned most sporting codes were adopting the black moniker and livery; our cricketers became the Black Caps and our hockey players the Black Sticks. The use of black escalated as it was deliberately chosen to promote anything that required a uniquely New Zealand identity. Tourism NZ and Creative NZ logos were rendered in black and our indigenous vodka, 42 Below, had black branding. We had begun to paint ourselves black and we were coming to own it.

In any crowded place it is obvious at a glance how black we have become, not just a black accent but a head-to-toe statement. Are there some innate characteristics that we possess that make this a comfortable fit? Looking at what we wear and what we have worn can reveal much about our society, about developments in technology, our place in the world and the evolution of our cultural identity. Our clothes provide a window through which we can view our history; seeing it not in the grand events of our history but in the personal experiences of a life. The stories and garments in this exhibition prompt us to consider why we choose to wear black.

Our Kiwiana speaks of an unpretentious nature in the black singlet and gumboots. Our uniforms and regalia speak of our conformist tendencies and our deference to authority, while our music expresses our nonconformity in lo-fi. Our sporting uniforms speak of our vigour and a necessary aggressiveness striving to be noticed on the world stage. The garments that have become fashion icons speak of our edgy but easy style. Black has many meanings but when we choose what we wear which do we fit?

Text by Doris de Pont. Banner image of David and Seon wearing Zambesi, 2016. Image © Marissa Findlay.

Published April 2020