Stories

Entrepreneurial Women in New Zealand Fashion

Late 1800s -

The story of fashion is predominantly a female one. Not only are women the main consumers of fashion, it is women's names that spring to mind when we think of the fashion business in Aotearoa today. Karen Walker, Trelise Cooper and Pieter Stewart are virtually household names and a whole new cohort, including Maggie Marilyn, Kiri Nathan, Keva Rands, Penny Sage and Georgia Alice, has more recently been favoured by fashion fans.

There is a generally held idea that it was the women’s liberation movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s that opened a fashion career pathway for women. Primarily, this is because little attention has been paid to the achievements of women in the historical narrative, leading people to believe that prior to that time women had an ancillary rather than a leading role in society and in business. Running the Show seeks to correct that misperception through the stories of some enterprising women who were the designers, manufacturers and the business entrepreneurs.

The Department Store

Many of New Zealand’s most fashionable department stores - Ballantynes, James Smith, Milne & Choyce and Smith & Caughey’s - were established by women; Esther Clarkson, Mary and Ellen Taylor, Mary Jane and Charlotte Milne and Marianne Smith respectively. All were early immigrants to this country who saw an opportunity to fulfil the need of the fast growing population for clothing. When their success made room for their husbands in the business, these women did not step down but rather remained actively engaged in the running of their stores.

Many of New Zealand's most fashionable department stores were started by women, including sisters Mary Jane and Charlotte Milne and Marianne Smith.

One of the few surviving Department stores, Ballantynes, began when Esther Clarkson turned the front room of her home in Christchurch into a shop and in 1854 advertised her 'New Drapery Establishment' in Cashel Street in the Lyttelton Times. The venture was so successful, her carpenter husband, David, built an extension at the front of the house which took the front room right out to the street. By the end of 1856, David's sister Elizabeth had joined Esther and the store had expanded to become a large two-storey shop. Esther named the business Dunstable House, for her birthplace in England. It became Ballantynes when, in 1872, it was sold to John Ballantyne.

Doing business as a woman had many challenges including the legal title to the property, both physical and intellectual. While a single woman could own assets, those assets would pass to a woman's husband if she married. Some of our women chose to remain unmarried and while the passing of the Married Women's Property Act in 1884 changed the law, women still had to contend with social attitudes about the 'proper' place of women and also about their capabilities. The limiting mindset of power brokers like bankers and investors can still be an obstacle to women in business today, but in spite of such constraints, many women made it work.

The Manufacturing Industry

People may recognise Lane Walker Rudkin as the name behind the iconic Canterbury sportswear brand, but few will know that the Rudkin in that trilogy was in fact Sarah Jane Rudkin. Sarah had brought her sock-knitting machine with her when she and her husband Alfred emigrated from England in 1887. She established a cottage industry from her kitchen in Montreal Street. It soon grew into a thriving commercial business and the house was expanded to accommodate new machinery and employees. Growing the business, however, was not straightforward as sourcing a regular supply of quality wool was a constant challenge. Although there was a huge amount of wool being produced in New Zealand, accounting for up to 50 per cent of total exports in 1880, Sarah couldn’t secure the consistent supply she needed to fulfil her orders. This led to her signing a supply agreement with John Lane and Pringle Walker's Ashburton woollen mill in 1904, thus establishing Lane Walker Rudkin Industries Ltd.

Sarah Rudkin. No Known Copyright Restrictions.

In Palmerston North a few years earlier, Mary Alice Stubbs, the owner of a Griswold hand-operated circular sock knitting machine, had already negotiated a similar set of challenges. She grew a cottage industry into a successful knitwear manufacturing business that is still operating today as Manawatu Knitting Mills.

Throughout the 20th century entrepreneurial and creative women established and ran successful fashion enterprises. Their designer salons, department stores and boutiques were stocked with garments that were primarily "made in New Zealand", often constructed on-site or within a few blocks of the retail premises.

The Designer Salon

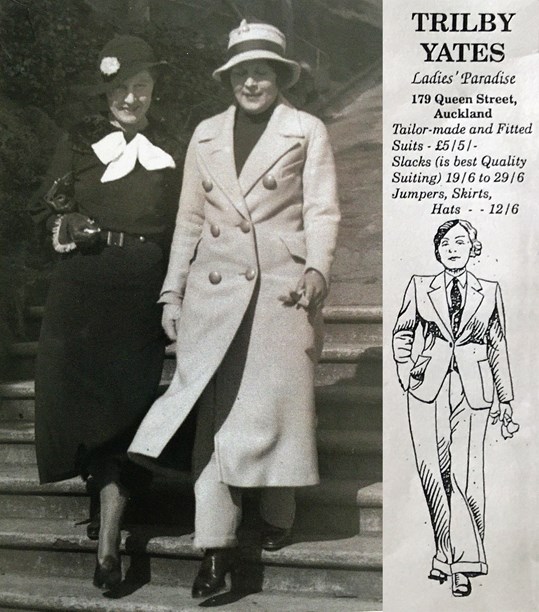

One such, Trilby Yates, had trained to become a milliner at the Bon Marché, a large millinery emporium on Auckland's Karangahape Road. In the mid-1920s she left her employ there to open her own hat shop, Trilby Yates: The Ladies Paradise, with her younger sister Julia. While it was said that Trilby could "take a tea towel and make a hat out of it", her sister could barely sew and instead attended to the administration and the salon. In the wake of Trilby’s early death, Julia took on the sole responsibility of running the business and of raising Trilby’s young daughter Digsy, whom Julia, who was and remained, a single woman, adopted.

Trilby Yates was a talented milliner who trained at The Bon Marché emporium on Karangahape Road in Auckland. Image © Trilby Asgher.

Julia employed a designer and added high fashion knitwear and bespoke womenswear to the millinery range. By 1936 the salon had moved to the other side of Queen Street and a nearby building had been purchased to house the workroom.

Julia travelled regularly overseas, attending fashion shows in Paris or New York, and would return home with fabrics and new ideas, including trousers for women. When, in 1933, she wore said trousers on Queen Street she caused an uproar but, undeterred, rarely wore anything else. The salon produced trousers for women and advertised them in the New Zealand Women's Weekly. The magazine, in its column 'Current Controversies', asked its readers, "Will they tempt the fair sex? Now girls what do you think? Should women adopt this fashion?" The answer came directly to the salon door in a rush of orders.

Julia Yates (right) wearing the slacks that caused an uproar when she put them in the window of her Queen Street store, Trilby Yates, in the early 1930s. Image © Trilby Asgher.

Before moving to Christchurch, Kathleen Fuller worked at John Courts Ltd, the Queen Street store that advertised itself as 'Auckland’s Leading Drapers'. In 1923 Kathleen set up her own business, Minerva Frocks, and in an unusual move for the time, advertised herself as a designer.

Photo of Kathleen Fuller. Image from Alexander Turnbull Library, PAColl-6411-15.

Flora MacKenzie learnt the dressmaking trade in Sydney before returning home to go join Mrs N Austin at Ninette Costumier, on Queen St in Auckland. By 1927, Flora was the sole owner of the business, now called Ninette Gowns. Her salon employed and trained others for careers in the industry, and for three decades she designed tailored dresses and suits and elegant gowns for a prosperous clientele who lived all over the country.

Flora MacKenzie in 1943. Photo courtesy of Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, 1622-001.

Technical colleges offered another pathway toward a fashion career, Druleigh, which opened in Auckland in 1927, being one of the most significant. Many Druleigh graduates found work in the industry or later, as married women with families, used their skills to generate an income through home-based dressmaking.

The Designer Manufacturer

One early Druleigh graduate, Maud Barrell, was first employed by Flora MacKenzie at Ninette Gowns in the early 1930s and later became the designer for Paramount Frocks. In 1941, her only child, Beverley, was born. As a woman with a successful career, Maud returned to work a few weeks after the birth of her daughter while her husband Jim played a large role in raising their daughter. When Paramount Frocks was put on the market, Jim sold his taxi business so that they could buy it. Renaming it Fascinator Frocks, Maud continued her design success, winning a gold medallion at the Industrial Jubilee Exhibition in Wellington in 1950. Following her win, she was asked to design an evening dress in a brand new fabric, nylon. Her design was exhibited alongside prestigious designers like Worth, Lanvin, and Digby Morton at the 1951 Festival of Britain.

Maud Barrell in 1940. Image © Beverly Ann White.

Emma Knuckey wasn’t a trained designer, but her fashion illustrations secured an invitation from English designer Frederick Starke for her to come and meet some of London’s top fashion designers. Inspired by what she saw in their salons and workrooms, Emma and her husband returned to sell up their Taranaki farm and settle in Auckland. While her husband drove taxis and looked after the children, Emma opened a workroom and salon, Gowns by Emma Knuckey. For nearly 25 years, she and her business partner, Betty Clark, ran a successful fashion label that was sold in shops and department stores throughout New Zealand.

Emma Knuckey in her upstairs workroom in Darby Street, Auckland City in 1965. Image © Auckland Star, courtesy of Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira, PH-2013-5-2-52.

The Promoter

It wasn’t only designers who were successfully establishing new enterprises. The post-war economic recovery saw increased affluence which gave birth to a new role in the industry, that of fashion promoter. This role entailed advocacy for the latest fashions and their promotion to the buying public through the organisation and presentation of fashion showings and events.

Samoan born Eleitino Paddy Walker, was one who led the way. With two young children and a husband recovering from tuberculosis, she stepped up. Approaching Sir James Hay of the Hay's Department store in Christchurch she suggested she become their 'fashion coordinator ', working with the buyers to spearhead a move toward more directional fashion and seasonal fashion parades. Her offer was accepted and she turned out to be very good at it.

Paddy Walker (centre) rehearsing models for a fashion parade in 1957.

Before Paddy arrived on the scene, fashion parades were very sedate affairs, with models simply promenading in a salon-style setting to show off the garment. Paddy changed all that, adding rhythm, structure, and musical expression to create dynamic choreographed fashion parades. Her shows became "must-see" occasions for Christchurch’s fashionable women. It was the beginning of a successful career working in the world of fashion that expanded even further when she moved to Auckland in 1952. Paddy was the woman behind the sold-out seasonal showings at Milne and Choyce. Her services were also keenly sought for charity fundraisers and important fashion events such as the one staged for Queen Elizabeths's Royal Tour in 1953-54.

Tam Cochrane was another with a talent for organising fashion events. In 1958, her company Tam Cochrane Fashion Promotions introduced the Gown of the Year competition to New Zealand. This was a touring roadshow with gorgeous dresses and live models that brought a sparkle to small-town New Zealand. The competition was judged by popular vote. Different categories, including sportswear and bridal, led to the climax of each show, ultra-glamorous evening wear made by local designers.

Fashion promotion, however, is not solely the prerogative of the fashion industry. Women who are running other shows can and have taken a strong and often unconventional role in advancing the cause through what they choose to wear.

Tam set up her business, Tam Cochrane Fashion Promotions, in 1954. Image © Gisborne Photo News.

Whetu Tirikatene-Sullivan is one such. Although primarily known as a politician she embraced the power of dress in her role. As a Māori woman with a lifelong passion for design and dressmaking, the clothes she wore made her a distinctive and visibly female presence in Parliament.

Whetu Tirikatene-Sullivan with other New Zealand politicians. Archives New Zealand reference ABGX 7574 W4969 3e.

Whetu helped establish a boutique in Wellington which sold Māori and Polynesian-inspired garments made by local designers. She wore these clothes herself and, consolidated by her public profile as Minister for Tourism, she affirmed and promoted contemporary Māori motif and design in Aotearoa and on the international stage.

The Family

When history and society share the stories of men and their accomplishments, family rarely features. How they marry their career with being a family man is not seen as relevant to the telling, but for our women entrepreneurs, it is central. Despite many legislative changes our society still expects women to carry the responsibility for the home and children, even if it is just organising childcare. Society pays attention to this and women who wish to pursue a career also want to know how others have managed this doubling of roles successfully.

Our entrepreneurial women provide valuable role models, demonstrating how family has been valued and factored in.

Most of our earliest examples developed their enterprises from home where they could attend to the demands of both. When their cottage industries grew, the home often grew to accommodate that development. Having children in the workplace, whether at home or away, was made a workable model by these pioneering women. Many who followed, such as Whetu Tirakatene-Sullivan and Annie McNeur, also embraced it as a functional option.

Whetu Tirakatene-Sullivan and Annie McNeur with their daughters. Images © Denis Sullivan and Annie McNeur.

A number of our women such as Mary Taylor and Flora MacKenzie, remained single and others such as Marianne Smith were childless. Mary Jane Milne and Julia Yates were both unmarried but were deeply committed to providing for the welfare of their nieces, nephews and wider family.

Support from family and partners is an important part of the story for many; Esther Clarkson’s carpenter husband, Maud Barell’s husband Jim and Emma Knuckey’s husband who gave up his farm so she could pursue her ambition. Other familial connections also came into play as in 1978 when Adrienne Winkelmann opened her boutique in the Mayfair Mall on Queen Street with start-up funding from her mother. Her sister, now Justice Helen Winkelmann, was her model and muse, introducing the Adrienne Winkelmann style to her professional friends; a solid start on which Adrienne has built a 42 year career trajectory as one of New Zealand’s most enduring and successful contemporary haute couture fashion designers.

Conclusion

Today Aotearoa's Prime Minister, Jacinda Ardern, demonstrates time and again that she understands what Whetu Tirakatene-Sullivan knew - that even though she is running a country and not a fashion show – what she wears can speak as loud as her words. She is a proud wearer of local designers and the names on those labels are mostly female.

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern at Ratana Pā in 2018 (photo © Nevada Halbert) and at the swearing in ceremony in 2017 she is wearing a dress by Kate Sylvester (photo courtesy of Governor General).

We don't always know what is learned from history but when we look at the women who work in the fashion business today we can see the same courage, innovation, determination, and commitment we have seen in these stories of our entrepreneurial women. While the social landscape has changed and the department store barely exists, designers like Karen Walker, with an international reach, have their name on the whole gamut from pants to paint to perfume.

Local manufacturing is again akin to a cottage industry with designers like Elizabeth Findlay at Zambesi stitching and finishing their designs in-house and Maggie Marilyn engaging a team of small-scale makers and artisans to produce her clothes.

Factories like Fascinator Frocks have been largely replaced by off-shore manufacturing but nonetheless the designers who produce at volume like Trelise Cooper and Paula Ryan still base their design and workrooms here.

Adrienne Winkelmann carries on the salon tradition of someone like Trilby Yates, with a select retail offering and the production of bespoke designer garments. Every day, more and more local designers like Ruby and Juliette Hogan are also entering the bespoke market.

Fashion promotion continues and although thanks to Pieter Stewart we have had our own homegrown Fashion Week for the last 20 years, today promotion relies more and more on digital platforms, giving our fashion a global reach. Clara Chon of Blue Blank was asked by Kim Kardashian to make her a selfie jacket after seeing her work online.

Designer Clara Chon (pictured here) was commissioned to make this 'selfie' jacket for Kim Kardashian West and it became a paparazzi magnet when the reality television star wore it in February 2016.

Maggie Marilyn is available on premier online shopping site Net-a-Porter, and Kowtow has close to 200 stockists worldwide from their flagship store in Wellington to Iceland, New York, to the Czech Republic.

Caption. Photo by Motion Sickness Studio, © Maggie Marilyn.

The inclusion of indigenous design ideas in our vocabulary has made Aotearoa fashion much more diverse. Designers like Kiri Nathan have made contemporary kākahu for our Prime Minister while Adrienne Whitewood was invited to create a collection of clothes for sale at our national museum, Te Papa Tongarewa.

Adrienne Whitewood at New Zealand Fashion Week, 2017.

The show might look different today but there are still entrepreneurial women who are taking a strong role in establishing and running their own business. We are telling their stories to ensure that their achievements feature prominently in the social and cultural narrative of Aotearoa.

Text by Doris de Pont.

Published October 2020.