Stories

Benson & Hedges Fashion Design Awards

1964–1998

As an Oscar is to actors, a Benson & Hedges Fashion Design Award was to aspiring New Zealand fashion designers. To be nominated for, or to win, one of these coveted awards, especially the Supreme Award for the most outstanding design over all, was considered the pinnacle of fashion achievement.

The country’s major competitive fashion event for 34 years, the B & H Awards, as they were popularly known, provided young talent and individual designers with a unique opportunity to show their work, free from commercial imperatives.

Organised by Jeannie Gandar, president of the New Zealand Modelling Association and senior tutor in Clothing and Textiles at Wellington Polytechnic, to raise money for charity, the first event was staged in Wellington’s Majestic Cabaret on 29 July 1964. Called the Wills Gold Rose Award for Design, after the event’s sponsor, cigarette manufacturer WD & HO Wills, it was compered by TV chef, the Galloping Gourmet's Graham Kerr and the models gave their services for free. The following year, the Wills name was replaced with that of their cigarette brand – Benson & Hedges.

Michael Mattar with his winning garments at the 1968 Benson & Hedges Fashion Design Awards.

The Awards, which were domiciled in Wellington and co-ordinated and compered until the end of the 1970s by Josephine Brodie, were held in the capital’s Town Hall and televised for broadcast at a later date.

Josephine Brodie, president of the NZ Modelling Association, was involved with the awards for 15 years.

Fashion events co-ordinator and compere Maysie Bestall-Cohen took over the organisation of the Awards in 1982 and, two years later, they went live-to-air from the Michael Fowler Centre in Wellington where they were presented annually for the next 14 years.

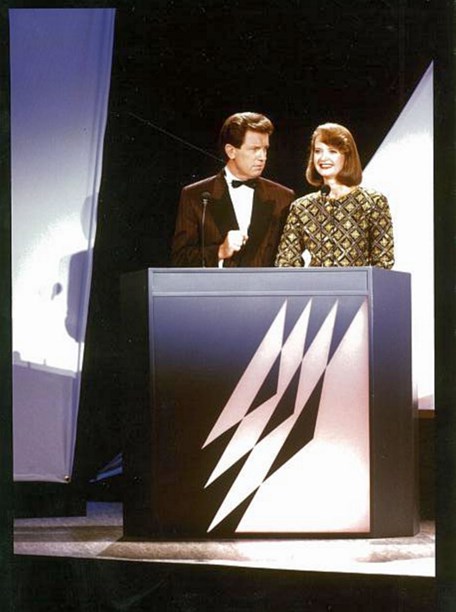

Maysie Bestall-Cohen with co-presenter John Hawkesby, Benson & Hedges Fashion Design Awards, Wellington, 1990.

The show was the country’s most spectacular live television event and one of the largest outside broadcasts of its kind. Hundreds of people, comprising broadcasting and fashion personnel, were involved in its presentation.

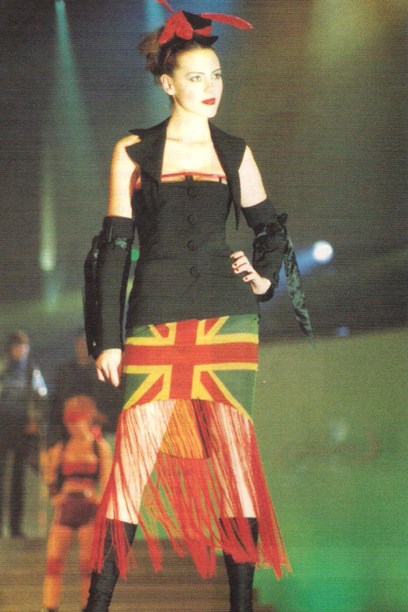

The Benson and Hedges Fashion Awards 1986.

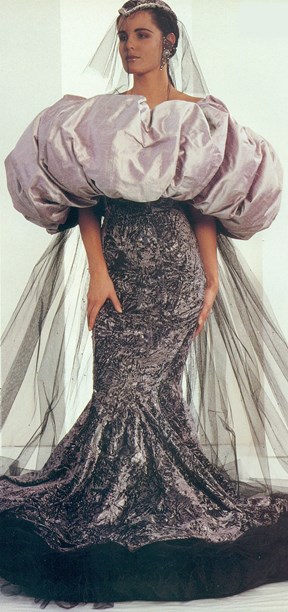

Initially there were two design classifications – High Fashion Daywear and Formal Eveningwear but as interest in the Awards grew more categories were added. Although these changed periodically, in order to keep pace with current trends, they always encompassed Leisurewear (casual daywear, sportswear), High Fashion Daywear, After-Five High Fashion (evening, theatre, cocktail) and, from 1973 on, the Young Designer Award and an award for design excellence in wool. The Menswear Award, axed in 1975 because of the poor quality of the entries, was reinstated in 1988. The After-Five High Fashion Award was renowned for its glamorous entries up until the mid-1990s when the sophisticated designs were replaced by more offbeat designs.

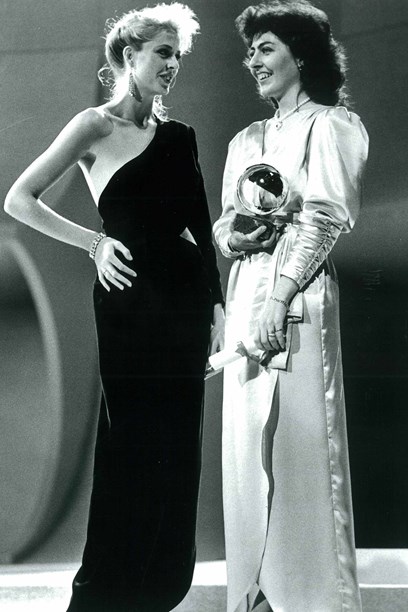

The Outstanding Evening Garment Award winner in 1982, Patrick Steel.

Among the specialist categories that came and went was the Leather Industry Award which highlighted the versatility of leather as a fashion medium and attracted many outstanding entires.

The Woolgrowers Award brought forth a spate of hand-spun, hand-knits and, in 1980, produced a Supreme Award winner, Milton farmer’s wife Elaine Fowler. Taking into account the growing influence of Māori and Pacific culture on fashion, the Oceania Award was added in 1995 and the Avant Garde Award, a forerunner of Wearable Arts, encouraged experimentation with materials as diverse as carpet underlay, fibreglass, astro-turf, PVC welders’ plastic and paper. The names of the designs in this category were often as inventive as the garments. WORLD designers Denise L’Estrange Corbet and Francis Hooper called their 1994 entry 'Jesus Christ is a Samoan Woman'.

‘Jesus Christ was a Samoan Woman’. A raffia bustier tops a black bodysuit and button-through hipster skirt in a religious print.

1992 saw the introduction of the Collections Award. In this category, designers were invited to create three co-ordinated garments (for men or women) based on a single theme.

Entries were examined for cut, fit, finish, colour co-ordination and appropriateness of fabric and judging was done in two stages. The 10 to 16 garments nominated in each category in the preliminaries then went on to the final judging. Three judges were drawn from within the ranks of the New Zealand fashion industry or fashion media, with the exception of 1971 when the judging panel was inexplicably made up of 21 journalists and radio and TV personalities of both sexes. Traditionally, a guest judge from overseas joined the local panel to select the winners. Guest judges included American Rudi Gernreich who launched the first topless swimsuit in 1964, Australian-based Colette Dinnigan and British designers Bruce Oldfield and David Emanuel, creator with his wife Elizabeth of Princess Diana’s wedding gown.

Tiered evening gown by Kevin and Val Marshall (Adobe), 1982. The guest judge that year was Warren Marx, fashion controller for the David Jones Group, Sydney.

For a few years, the best of the un-nominated garments were featured in a Highlights parade presented to the audience as a preliminary to the televised show. "Sometimes the standard was so high," says Maysie Bestall-Cohen, "it was heart-breaking to let a designer know they hadn’t reached the finals. Having a garment modelled in the Highlights parade was an acknowledgement of its merits." The Highlights parade was eventually discontinued as the logistics of transporting such a large number of clothes from Auckland to Wellington became unsustainable.

The B & H Awards were egalitarian, setting them apart from other fashion design competitions of the time. Professional designer or amateur dressmaker, anyone with a flair for fashion could enter. Thousands of hopefuls tried their luck over the years. Some, such as Patrick Steel, Young Designer of the Year in 1979, and Konstantina Moutos, the first designer to win three awards on the one night (1984) and the Supreme Award twice, went on to forge successful fashion careers. For others, having a garment shown in such a high-profile event, and on television, was reward enough.

The After-Five High Fashion and Supreme Awards winner in 1986, Konstantina Moutos.

Motivation often made up for lack of experience. In 1987, 17-year-old Christchurch Sixth Former John Juriss made news when he walked off with the Wool Award. Two years later, another 17-year-old schoolboy, Andrew Horton from Invercargill, won in the same category. The Young Designer Award, restricted to those under the age of 25, attracted entries from many emerging designers, notable among them, Kerrie Hughes, Anne Maree Chambers and Susanna Williams, the award-winner in 1982.

The Young Designer of the Year Award winner in 1982, Susanna Williams.

For some entrants, the Awards provided the opportunity to make a political or social statement. French nuclear testing in the Pacific, environmental issues and the AIDS epidemic were just some of the topics addressed in the guise of fashion.

Le Bombe by Lisa McEwan, highly commended in the After-Five High Fashion category in 1988. The dress represents a mushroom-shaped cloud, the veil represents acid rain.

In the early years, there were separate Awards categories for fashion manufacturers. In 1984, these were replaced with a non-competitive showcase, Salute to New Zealand Fashion, which allowed Thornton Hall, Love Story, Peppertree, Dreamgirls and other rag traders to present a themed showing from their current collections. The Fashion Hall of Fame was another later addition, introduced in the 1990s in recognition of former winners.

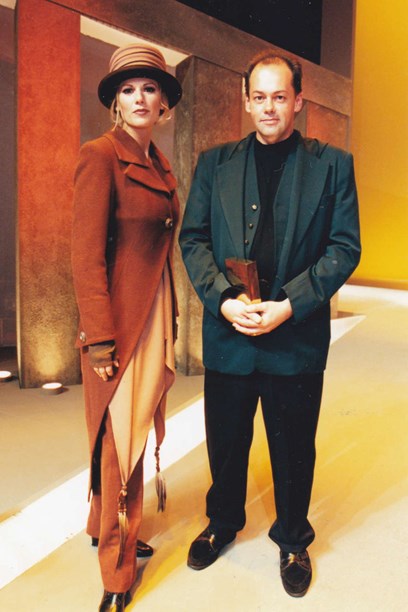

Paul Chaplin with his award-winning design, 1994. Image © Paul Chaplin.

Following the abolition of cigarette sponsorship by the government in 1995, the Health Sponsorship Council took over as the Awards’ naming rights sponsor. Known thenceforth as the Smokefree Fashion Awards, the event was given a three-year reprieve, after which time a new sponsor had to be found. As none were forthcoming, the last event took place in 1998. 363 designers entered. The first show in 1964 attracted 14.

Vaughan Geeson won Young Designer of the Year in the final Smokefree Fashion Awards in 1998.

The official Awards material - photographs, videotapes, press releases and cuttings - is now archived in the Alexander Turnbull Library where it can be accessed on request.

Text by Cecilie Geary.

First published January 2014, updated February 2019.