Stories

The Gentle Wrap

A distinctive feature of how we like to clothe ourselves in Aotearoa today is the unstructured and easy fitting tunic or dress, a style that gently wraps the body, providing shelter from the elements and protection from unnecessary scrutiny. It is a choice with a history in the Moana and also one that suits the culture of easy dressing which we embrace as part of our Aotearoa identity.

The most basic piece of textile is a simple length of material, often described as a wrap. The word 'wrap' encapsulates important actions that are part of the human relationship with cloth: swaddling, enfolding, binding and containing, and our feelings of these is deeply ingrained and integrated into our physical memory. Our primal life experiences of warmth, comfort, protection and belonging are at the heart of clothing across all cultures.

The early European navigators to the South Seas, such as Cook, Bougainville and Bligh, witnessed a deep connection to cloth, documenting its use for garments and for ceremonially wrapping objects and people. There are extensive descriptions of how island cloth which was worn wound around the body was unwrapped, like the shedding of a skin, and then presented and wrapped around the recipient. The cloth has been imbued with the mana, the very DNA of the gift giver. The European exchange garment too should be an item of worn clothing. These transactions in cloth embody a mutual shaping through wrapping in each others’ skin.

The everyday wearing of cloth was also documented by Cook in Tahiti in 1769: "Their clothing are either of Cloth or matting or several differen[t] sorts ... the dress of both men and women are much the same which is a piece of Cloth or Matting wraped two or three times around their waist ..." (Cook in The Journals of Captain James Cook, Beaglehole, J.C., ed. London, Hakluyt Society, 1955).

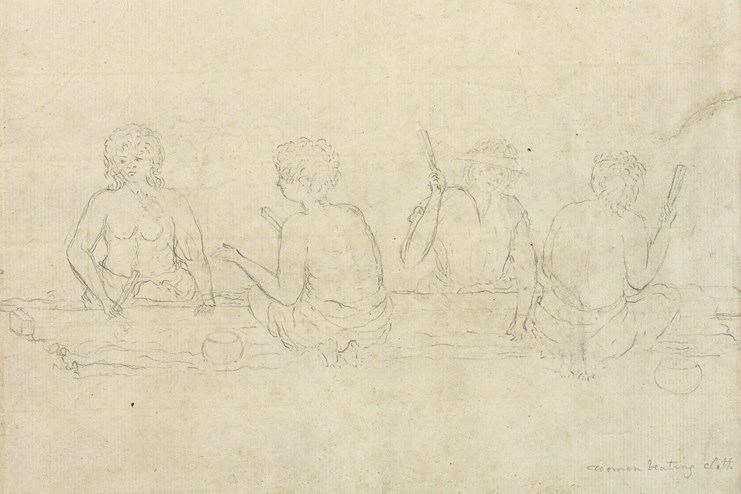

Sketch by Sydney Parkinson, which he captioned ‘women beating cloth’. They appear to be wearing barkcloth wrapped around their waists with one wearing what looks like a tiputa. Image © The British Library Board, ADD.23921 F.50.

With only a few other garments noted such as tiputa (a length of cloth with a hole in the middle for the head worn like a poncho) it would appear that wrapping was the default way of wearing cloth for the people of the Moana. The basic non-gendered wrap garment worn by men and women alike has survived the impact of missionaries, colonists and the migration to Aotearoa and remains essential in the Moana wardrobe. ‘Ie lavalava, the Samoan name for a cloth that wraps around, is a garment recognised all over the Moana. Formal male renditions of wrap skirts based on European tailoring with pockets and a waistband are seen in the sulu in Fiji, ie faitaga in Samoa and tupenu in Tonga. For women we see the Samoan puletasi and the Tongan puletaha, a two-piece ensemble of wrap skirt and tunic. For special occasions and for performances, decorative layers of tapa cloth or other waist ornamentation is wrapped over the top of the skirt as a signifier of formality and as an expression of belonging within the inclusive nature of wrapped Moana cloth.

On the streets of Aotearoa a version of the trope is demonstrated in the Sam’s Island Gear 'Otara Love' t-shirt worn with a print lavalava, by Onehunga based label Tanoa, wrapped over pants; a look that music group Te Vaka introduced to the world stage in 1997.

A printed lavalava by Onehunga based label Tanoa, wrapped over pants. Photo by Edith Amituanai, model Hezekiah James Setu.

In Aotearoa the temperate climate dictated the need for warmer clothing and the cloak became an essential garment for Māori. They developed all manner of iterations that could be wrapped around the body for protection from rain, for warmth and for ceremony.

This wrap form can be seen in a number of the garments in Moana Currents. Shona Tawhiao has chosen to use parka nylon for her tiputa (poncho), wrap skirt and padded neck wrap. Ema-Lea Phillips has cut strips of cotton drill and created a new yarn to crochet a protective cloak for her 'Urban Warrior'. Emilia Wickstead uses fine merino wool for her wrap, its drape as soft and pliable as a prized Māori muka kaitaka (fine woven flax cloak). Steve Hall mimics a cloak in the wraparound overgarment he has embellished with tags tied into bows and worn over his striped mu’umu’u.

Wrap garments in Moana Currents by Shona Tawhiao, Ema-Lea Phillipps, Emilia Wickstead and Steve Hall.

The success of the mu’umu’u, a loose garment shape inextricably connected to island women from Papua New Guinea to Hawai’i, is linked not just to the successful conversion to Christianity but also to the original wrapped forms and the tiputa.

Early European explorers had seen both men and women wearing 'aprons' and waist wraps made of bark cloth, woven fibre, leaves or grasses. The women's bared breasts were largely interpreted through a Western lens, as overt sexual display. Missionaries arrived to redeem the 'heathens' souls by introducing them to their own civilising beliefs and practices which included teaching fine needlework and garment-making skills so that they could replace their immodest manner of dress.

The garment chosen for their converts was a dress constructed from some lengths of fabric fitted to the body by means of stitched tucks across the chest and shoulders or gathered onto a yoke. The smock hung freely to the ground with its full sleeves gathered to the wrist. They were simple garments to make and fulfilled the Victorian desire to cover up. There is much speculation about the origins of this design as it bears no resemblance to Western fashion of the time but rather resembles what were known as 'at home' dresses, garments worn for comfort in private, during pregnancy and, ironically, given the missioners’ intentions, by prostitutes.

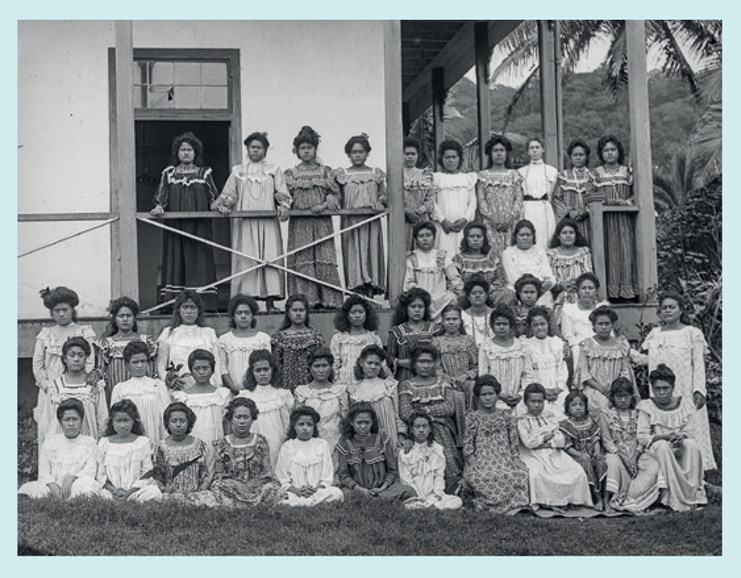

A group of Samoan girls in European clothing on the porch of a Western-style classroom with their teacher. Possibly Papauta Girls School, near Apia, 1890s. Photograph by Thomas Andrew, courtesy of Te Papa, C.001463.

For the missioners, the mu'umu'u became a symbol of the success of their endeavours. For the island women the ready adoption of these dresses probably had other motivations as well as being indicators of their conversion to Christianity. While there is some evidence of this style of dress being manufactured in barkcloth and indigenous woven cloth, photos show that imported plain and printed cloth became the material of choice.

The English cottons were often printed with flowers, a decorative element which was appreciated by Victorians and islanders alike. Manufactured fabrics also gave island women a less labour intensive and more durable source of material for their homes and wardrobes. In combination with the newly acquired art of embellishment using lace, crochet, embroidery and appliqué, local women acquired an enriched creative seam that they could draw on. In 2018 an embroidered and wrapped gown, a collaboration between Cook Island ta'unga tivaivai Tukua Turia and the Kuki Airani Mamas and designer Karen Walker represented Aotearoa at the inaugural Commonwealth Fashion Exchange at Buckingham Palace.

Tivaevae gown by Karen Walker and the Kūki ‘Airani Creative Māmās. Images courtesy of Karen Walker.

Women's active engagement with the new cloth and all its possibilities has helped the missionary dress's evolution into the formal Sunday dress and the variety of styles seen in modern puletasi, puletaha, and mu'umu'u.

Dru Douglas's first collection under his label, Lumai, included this dress inspired by a garment traditionally worn by women in Papua New Guinea - the meri blouse. Photo by Mara Sommer, model Layla Dole.

In Aotearoa our more temperate climate mitigated against the ready adoption of this 'mission'-style dress by Māori who instead appreciated the warmth and labour saving qualities inherent in imported woollen garments and blankets.

It wasn't until the 1990s that this 'mission'-style dress entered our fashion lexicon as part of a new understanding of our identity. Spurred on by globalisation which saw the rise of global brands such as McDonald’s and the introduction of the World Wide Web in 1989, nations were looking for markers of distinction and saw that uniqueness could be mapped onto narratives of place. In Aotearoa we found a meaningful location in our geography as islands in Te Moana nui a Kiwa, the great ocean of Kiwa.

Located at the edge of the world, we framed ourselves as outsiders, innovators, non-conformists; a position that allowed us to be relaxed in our lives and in our dress. This conceptualisation of ourselves was addressed in garments that offered protection and comfort without constraining our activity. The loose and layered look, fashionable in the 1990s, became emblematic markers of Aotearoa style and even when this fashion moment had passed, we did not abandon these characteristics. Today almost all of the garments gathered in Moana Currents from Trelise Cooper’s silk tiered dress to Keva Rand’s tangelo linen Mama dress, express that aesthetic. It is a choice that has parallels in the history of island women’s embrace of the mu’umu’u. We have adopted the culture of easy dressing because we like how it fits our identity, it suits us.

Text by Doris de Pont, banner image of the Tivaevae gown by Karen Walker and the Kūki ‘Airani Creative Māmās, photographed by Sam Hartnett, courtesy of Te Uru.

Published November 2019.