Stories

Urban Jungle

"To wear leopard you must have a kind of femininity which is a little bit sophisticated. If you are fair and sweet, don’t wear it," wrote Christian Dior whose debut New Look collection in 1947 featured a long leopard print evening gown with a short train, and a belted leopard sheath called Jungle.

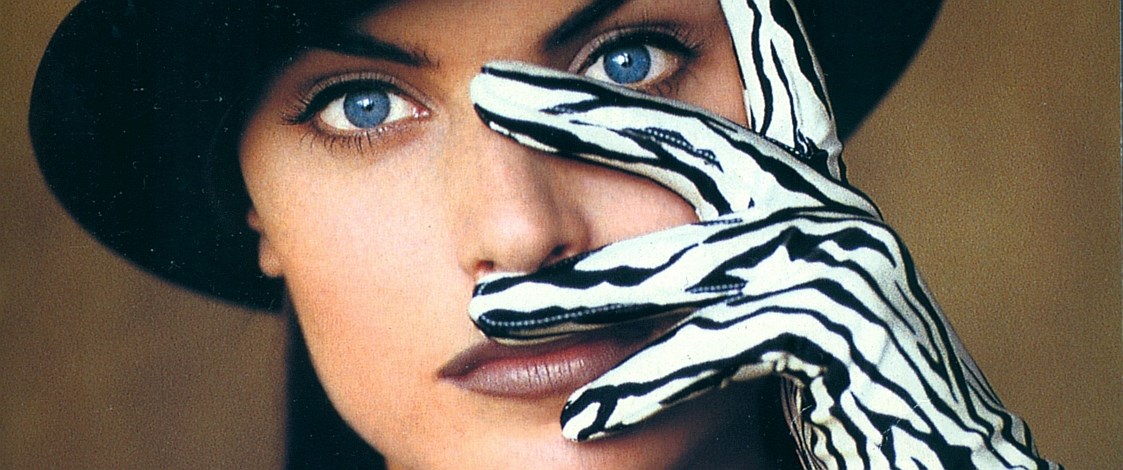

When it comes to animal prints, the leopard has always been the king of the cats. But in 2019, fabrics printed to resemble the patterned skin and fur of tigers, ocelots, zebras and snakes are also making news. Designers, both here and overseas, have answered the call of the wild, celebrating the animal print in a variety of ways. While the filmy, leopard spot voile slip dresses and play-clothes at Juliette Hogan, and Lonely’s diaphanous leopard dresses and Ts, purr rather than roar, the zebra pieces by Moochi and Kate Sylvester, and Trelise Cooper’s exuberant fauna and flora prints, are bolder and more graphic.

Leopard-print pieces from 2019 Cooper collection by Trelise Cooper.

In the past, depending on your viewpoint and by whom it was worn, leopard-patterned clothing was considered either classy or déclassé. On fashion icons like Princess Grace (formerly Grace Kelly) and Jacqueline Kennedy, both of whom owned real leopard-skin coats, it denoted status, wealth and style. Such was the demand for copies of the boxy leopard coat designed for Jacqueline Kennedy by Oleg Cassini in the 1960s, thousands of leopards were killed for their skins, leading to the passing of the Endangered Species Act of 1969.

Warren Smith remembers Kaye-Marie Cruikshank, the society milliner whose salon was a few doors down from John Greer’s, the shoe shop he managed in Auckland’s Vulcan Lane in the 1960s, sweeping into work wearing a full-length leopard-skin coat and matching hat. He assumes the fur was real, not fake. If it was, says Evan Tosh, a former manager of Fur Dressers and Dyers, the company which processed skins for Mooneys Furs, it would have been bought overseas. "Leopard-skins were never brought into New Zealand for use by the fur industry. In the UK, leopard patterns were screen-printed on less costly furs but that wasn’t done here either."

By the late 1950s, imitation leopard fur, made from a variety of synthetic fibres including acrylic, modacrylic and polyester, had become the fashionable, ethical and affordable alternative to the real thing. Popular for coats and as a trim, it was also sold by the yard in fabric shops and department stores. Describing a moss green El Jay coat she bought in 1959, former Dunedin window-dresser and milliner Hazel Craig says it had a leopard collar that reminded her of Hollywood and made her feel like a star.

Vinka Lucas wears a leopard-trimmed suit with matching scarf and umbrella. 1960s.

In the 1960s, New Zealand teenagers, who had never known the luxury of owning a real fur, were happy to accept the man-made version, teaming above-the-knee faux leopard coats with long leather boots and often a matching hat. During this period, Wellington’s Treister Hats turned out hundreds of animal-print hats in several styles. 'Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat', a song written by Bob Dylan in 1966, was purported to be about Andy Warhol superstar Edie Sedgwick.

Arnold animal-print fake fur hat. Treister Hats, 1960s.

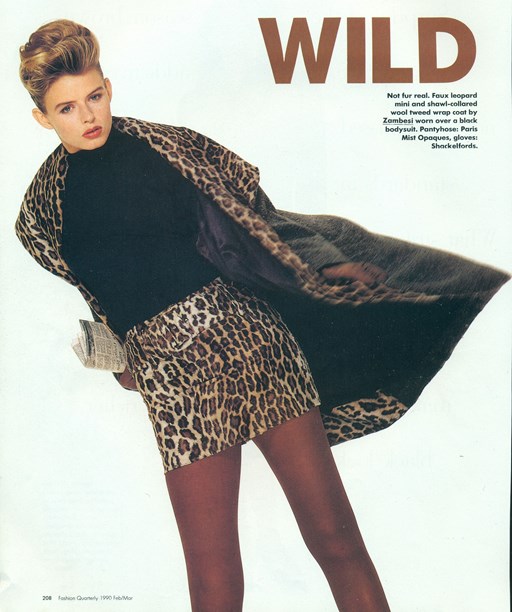

An attempt to revive the mini at the beginning of the 1980s proved to be a bit of a fizzer, but by the end of the decade it was back, sassier than ever in fabrics like leopard fake fur. Designer Doris de Pont wore her leopard mini with a black polo, black tights and a big belt. A shorter-than-short Zambesi version came with an optional extra – a leopard-collared wrap coat.

Faux fur-print leopard mini-skirt and coat by Zambesi, 1990.

Trelise Cooper is a designer who has shown an enthusiasm for animal prints since launching her first label Limited Editions in the mid-80s. One of her early designs, a bronze silk 'puffball' cocktail dress with a leopard fur strapless top, featured in Cha Cha magazine in 1987. It had a matching fur hat and wristlets, a novel accessory idea at the time.

Trelise Cooper for Limited Editions cocktail dress. Cha Cha, 1987.

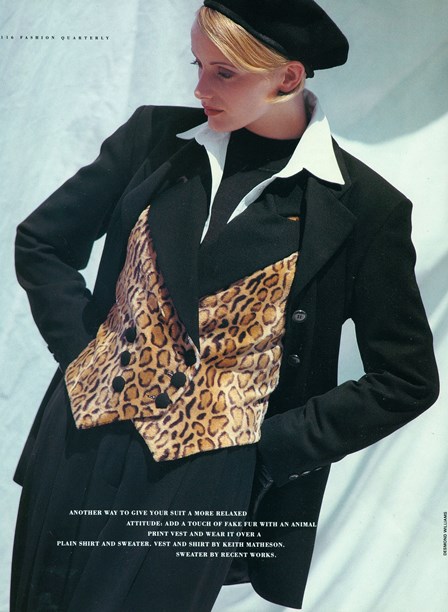

While snakeskin and pony-printed dress fabrics and vinyls appeared briefly from time to time throughout the early 1990s, the leopard’s reign was never seriously challenged. The tawny tones of faux leopard were the perfect foil for black, and Keith Matheson, Barbara Lee, Adrienne Winkelmann and other designers used it lavishly, embellishing little black suits and coats with fur collars, pockets, edgings and cuffs.

Black suits by Jeanmakers (a Keith Matheson label) and Adrienne Winkelmann (with leopard skirt). Fashion Quarterly 1990.

At one stage, leopard waistcoats, designed to be worn under a plain black jacket, were immensely popular. These ranged from basic vest shapes to more complex pieces intended to be the focus of attention.

Double-breasted waistcoat with black rever collar by Keith Matheson. Fashion Quarterly 1993.

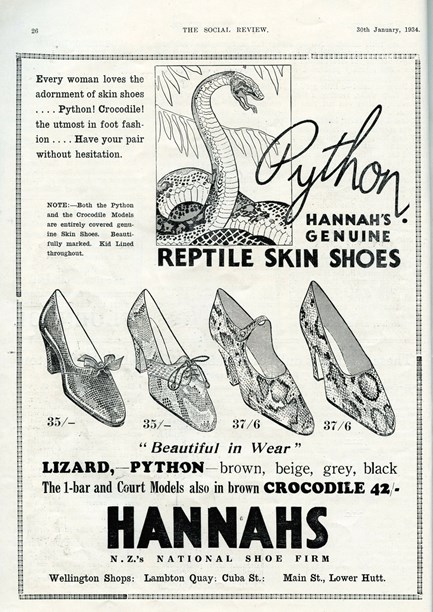

In 1934, Hannah’s, NZ’s National Shoe Firm, (founded in 1868), advertised 'genuine reptile skin shoes'. Equivalent in status to a real leopard-skin coat, the crocodile models were slightly more expensive than the python and lizard designs. All were kid-lined. Reptile skin handbags, mainly soft shapes or clutches, were the height of fashion then, too.

Hannah's ad for reptile skin shoes, 1934. Image from The Social Review, courtesy of Wellington City Libraries.

When David Elman first began manufacturing shoes in the 1950s, it was still acceptable to use skins such as lizard, water-snake and python. After the practice became unethical, the company resorted to animal-printed fabric or embossed leather, in order to be up with the play. "The appropriateness of the shoe with the latest fashion look was important to us," says David Elman’s Brook Monks. "We always looked ahead to the next season. The look had to work as a whole." In 1993, a big year for animal prints, the David Elman collection included animal-print boots, flats and heels. Marler Shoes also incorporated wild animal patterns in their designs. Marler Shoes and David Elman are no longer in business but contemporary New Zealand shoe designer Kathryn Wilson has carried on the tradition, producing animal-print footwear in a variety of styles.

Shoe advertisements, 1993.

Any part of an animal can be called an animal print. The term isn’t confined to the pattern on skin or fur. DNA’s 2003 winter collection, Where Wild Things Are, featured an ostrich-leg print on mesh pieces, dresses, tights and tops. Scaled wild things were hinted at in corduroy pants with a skin finish, and animal-print stretch panne velvets were made into briefs, leggings and fingerless gloves. The collection, which evoked an illusory jungle of the mind inhabited by dreamlike creatures that were part animal, part bird, was presented at New Zealand Fashion Week in 2002. British fashion historian and author Colin McDowell lauded the designers (Doris de Pont and Adrienne Foote) for their creative spirit.

DNA Where Wild Things Are collection, New Zealand Fashion Week 2002.

The safari-look is another fashion trend synonymous with the jungle theme. One of Yves Saint Laurent’s most iconic pieces is a safari-inspired mini dress (1967), laced up the front and worn with a low-slung belt. It wasn’t until 1985, however, and the release of Out of Africa, that the safari-look really took off. Taking their cue from the costumes in the movie, designers turned out a slew of midi-skirts, jodhpurs, shirts and patch-pocketed, belted jackets in neutral-coloured linen, cotton and drill.

Safari separates by Thornton Hall (with pith helmet) and Montage by Barbara Lee safari jacket (with tortoiseshell buttons). Fashion Quarterly 1980s.

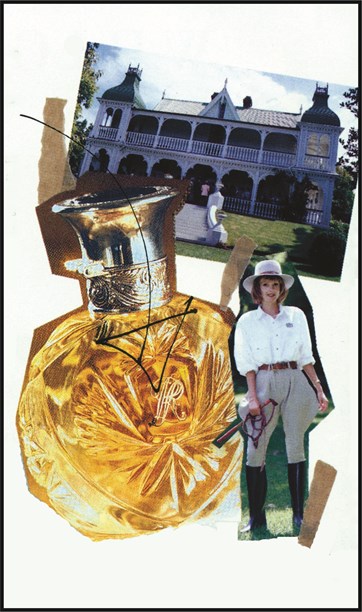

In 1993, Ralph Lauren, who did much to popularise the safari-look, introduced Safari, the scent, a green floral pitched at 'women with an independent and adventurous spirit'. Its New Zealand launch was held at Auckland’s historic Alberton house. In true Out of Africa style, guests lounged in wicker chairs on the verandah, sipping long cool drinks served by hostesses dressed in safari shirts, jodhpurs and tan leather belts.

Ralph Lauren Safari fragrance launch, Alberton, Auckland 1994.

Derivations of the safari/explorer look have resurfaced recently on international catwalks. The colour references are the same – cream, white, taupe, khaki – but, with a few exceptions, the interpretation is less literal than it was in past decades. One of the key pieces is the shorts-suit, comprising an unstructured jacket and the long, wide shorts beloved of the Brits in the tropics, in the days when Britain still had an empire.

Linen shorts-suit from Juliette Hogan spring/summer collection 2019.

Safari-looks are unlikely to lose their nostalgic appeal, just as animal prints, with everyone from Michelle Obama to Lady Gaga wearing them, are unlikely to lose their bite. The urban jungle theme is one that will continue to be explored for some time to come.

Text by Cecilie Geary. Banner image from Fashion Quarterly, 1993.

Published August 2019.