Stories

Tie-ing the Knot: The Neckwear Evolution

As one of the few decorative garments in a man’s wardrobe, the tie carries a lot of responsibility. It may be a small piece of clothing with no apparent practical purpose, but the significance of the tie in men’s fashion can’t be understated. And it's not just men who have worn a necktie. The trend for wearing ties as a fashion item isn’t strictly a male prerogative.

Remarkably for such a minor item of clothing, the choice of tie can be very revealing. It is an identifier of changes in society, in the economy and in fashion; the tie has been as wide as a handspan and as skinny as a licorice strap, it has been seen in modest muted tints and in garish fluorescent brights, it has been worn with decorum and with a subtle sense of humour. The variety of colours, patterns, materials, widths and knots has given generations of New Zealand men a way to express their individuality while conforming to the appropriate dress code prescription of the day. With a 100-year-old history of making ties in New Zealand, the Parisian Neckwear archive offers a unique record of these changes.

A century of ties made by Parisian Neckwear.

The earliest examples of neckwear appear to be limited to military attire. The terracotta warriors, guardians of the tomb of China’s First Emperor Qin Shihuang, for example, wear a broad scarf around their neck. Four hundred years later Roman soldiers reportedly wore cravat-like garments as part of their uniform.

The word 'cravat' emerged much later in the 17th century. It emerged after Croatian soldiers, who wore a piece of cloth around their neck as part of their uniform, travelled to France where their neck attire was adopted in the French court. The 'Croat' was corrupted to become 'la cravate' – the name for necktie in French to this day.

The fashion for extravagant and flamboyant menswear led to the widespread adoption of men's neckwear. Elaborate cuffs, ruffles and oversized collars appeared in the fashion lexicon, and the cravat became firmly established in the male wardrobe.

From the early 19th century, as men’s fashion moved away from showy, brightly-coloured attire to more sober colours and styles, men were looking for other forms of embellishment. With wigs, bows, breeches and lace long out of fashion the only acceptable way for a man to wear colour or pattern, was in his cravat (although some also found artistic expression in a coloured waistcoat). The cravat, in all its permutations became a source of creativity, spurred on by a book published in Paris in 1827, L’Art de Se Mettre la Cravatte, which illustrated 22 ways to tie a cravat.

Cover illustration of the book L’Art de Se Mettre la Cravatte, 1827.

The appearance of the more modest 'four-in-hand' or sailor’s knot in the 1860s introduced the use of a narrow length of fabric that was to become the necktie. This gradually began to replace the more bow-like cravat.

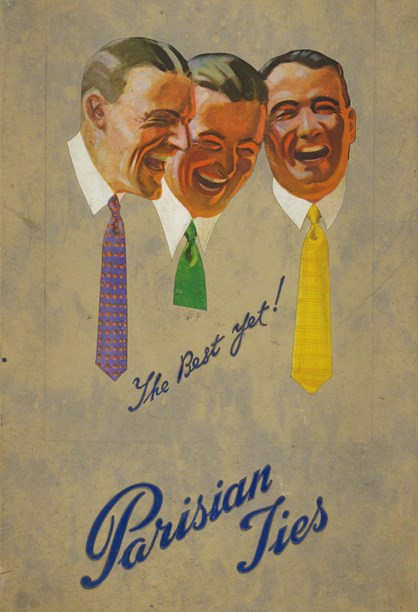

It was this type of tie that Parisian Neckwear started making in Auckland in 1919. Rather than relying on "the loud colours and weird designs which 'go' in some countries" - the style of necktie that was being imported - Parisian made ties for "the average New Zealander". While New Zealand men didn’t generally adopt the brightly coloured ties worn in America and Europe in the 1920s, playful prints and patterns were popular here.

Ad from the Northern Advocate, 1927.

Until the late 1920s, men’s ties had a short life-span. More like a scarf than a tie, they were made from a single strip of decorative fabric and the repeated knotting and unknotting caused them to crease and wrinkle.

From 1926 the three-piece bias-cut tie replaced this design. The manufacturing process became much more complicated and refined and today it takes about 14 different steps to make a tie. As a consequence the end result is a remarkably durable and elegant piece that could withstand the rigours of constant knotting, tugging and untying, with good grace. Fabric design was also transformed by bias-cutting as ties, now cut out at a right angle to the edge of the cloth, caused diagonal stripes to become horizontal and other unwanted effects. Tie material had to be printed or woven on the angle at which it would ultimately be cut and made.

The tie’s importance as a 'sign of belonging' reappeared and increased during the 20th century. Men wore ties that signified their membership of clubs, societies such as the Freemasons, army regiments, universities and schools. So much pride and prestige were attached to belonging to these groups that to wear a tie to which one was unentitled was considered bad form.

This Parisian tie was worn by members of the Ancient Order of Foresters. Image from Auckland Museum, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

During the 1930s, necktie fashion was for a wide and short look, and the introduction of new weaving technology made previously expensive brocade patterns more widely available and at an affordable price. Small neat regular patterns were common while bright geometric designs were also available for the bold. Men often tied them with a Windsor knot that added bulk and made the knot symmetrical. The knot is so named thanks to a key fashion arbiter and influencer of the era - the Duke of Windsor.

The Duke of Windsor wearing a tie tied in a 'Windsor' knot, 1945. National Archives and Records Administration. Office of Presidential Libraries, Harry S Truman Library.

Fashion in ties, like most other fashions during the war years, was constrained and unobtrusive. But when the Second World War ended in 1945, a new optimism gradually permeated and influenced everyday wear. Ties became infused with colour and patterns stood out in bold relief.

Ad for Parisian Ties, 1950s. © Parisian Neckwear.

The narrow tie emerged in the late 1950s - a style designed to complement the narrower, but wider set lapels of the era. Men wore slim-fitting suits and usually single-breasted jackets. The top suit jacket button was lower which made more of the tie visible. Ties in the 1950s were mostly made in a minimal design - solid colours or ties with a stripe or simple motif. The narrow tie was worn in New Zealand well into the 1960s.

Barney and Digby Crompton with the Parisian sales team, early 1960s. Image © Parisian Neckwear.

As new man-made materials emerged, tie makers started experimenting with new fabrics such as Trevira. The striped 'Trevira and wool' tie was a big-seller for Parisian.

Stripes were 'in' in this window display for Parisian Ties. Image © Parisian Neckwear.

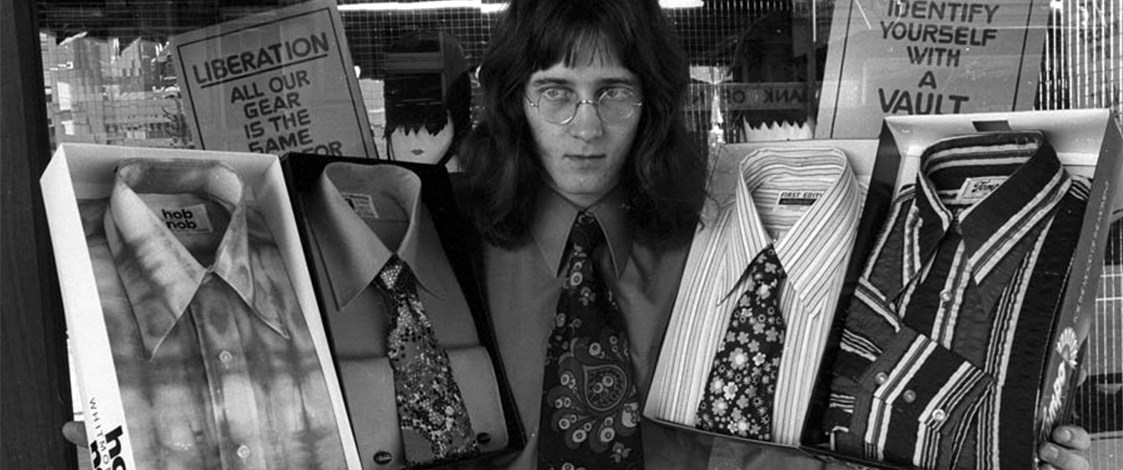

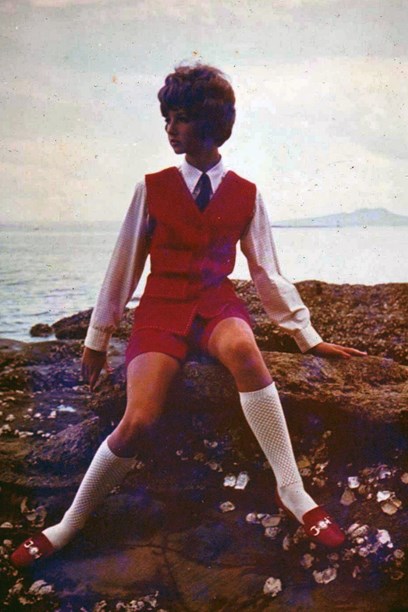

Ties grew wider and wilder as the 1970s progressed. They were designed to make a bravura statement in keeping with the era's quirky, expansive and flamboyant collars and jacket lapels. Bright, heavily patterned ties were often worn with shirts that had just as much going on. Pattern on pattern dominated.

In the 1970s, patterned ties were worn with shirts that had just as much going on.

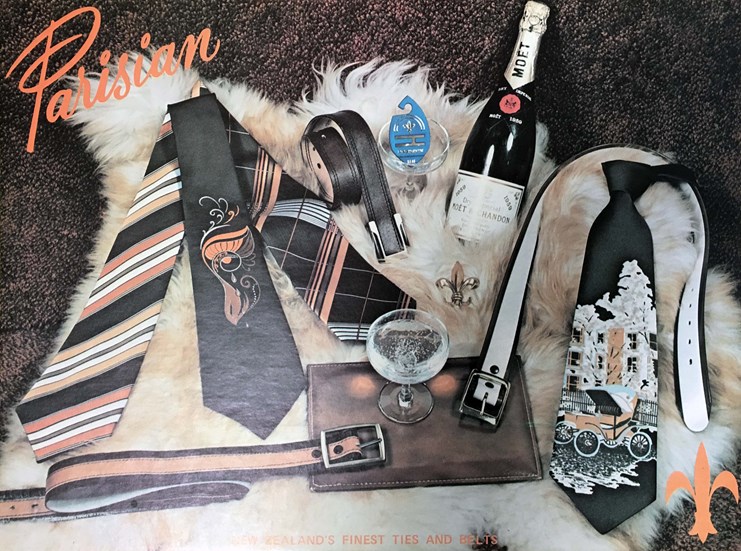

For men who weren't quite as bold, a tie in a more subdued brown or traditional stripes was preferable. That expansive width remained however.

Ties were advertised as a luxury item in the late 1970s. Image © Parisian Neckwear.

In the 1980s, the suit said it all and ties assumed a more modest role. Muted colours and smaller, formal patterns dominated. In the boardroom the power and status of the bespoke suit would have been negated by a flashy tie.

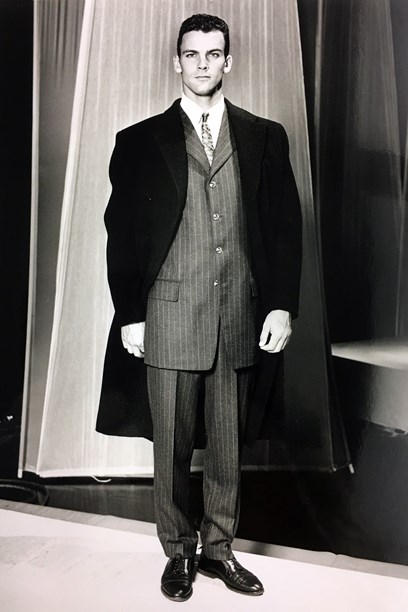

This coat and suit by Mark von Roosmalen was Highly Commended in the Menswear category of the 1989 Benson & Hedges Fashion Design Awards.

During the 1990s, the fashion for understated suiting and fabrics in neutral colours paved the way for the return of the statement tie, featuring abstract prints, cartoon characters and other novelty imagery. Paisley and small floral prints were also a popular choice that is also worn today.

After a brief revisit to the slim tie, led by European designers in the 2000s, ties are now available in a wide range of widths, cuts, fabrics and patterns. Today, the tie is no longer obligatory even in the corporate world. "This makes the development of collections so much more exciting, because when someone buys a tie, they are buying with far more interest and personal expression than for simple conformity," says John Crompton, fourth generation custodian of Parisian’s collections. Today’s tie wearers can define their look in a far freer way than in the past. Ties are enjoying a resurgence as an accessory in luxurious formal modes, but equally so in adding a twist to a more rustic casual styling.

Although the necktie is traditionally associated with men, old photographs show that, as far back as the late 19th century, New Zealand women wore ties too, for cycling, other outdoor pursuits and as an office uniform.

Image from Nelson Museum, ref. 53289.

In 1911, the 300 or so staff at Auckland department store Smith & Caughey’s, assembled to have their picture taken. While most of the women are dressed completely in black, a few are wearing long black skirts, white blouses and dark ties.

Whenever the menswear aesthetic in women’s fashion resurfaces, the tie is usually the accessory that completes the look. Movie stars who adopt an androgynous form of dress, such as Marlene Dietrich (1930s/1940s) and Diane Keaton (in the 1977 Woody Allen romantic comedy Annie Hall) are often the source of inspiration.

Early on in her career, Auckland fashion designer Jane Daniels and her mother Bette produced a range of ties for women under the BJ label, and later transitioned into making ties for men.

Jane Daniels wearing a BJ tie, 1970s. Image © Jane Daniels.

In the mid-1980s, Fashion Quarterly picked up on the trend, teaming fabric and knit ties in foulards, patterns and plains with knit separates, coats, tweedy suits, blazers and kilts. The advice to readers: loosely knotted is best.

Another tie moment in women's fashion occurred in 2001, with international and local designers alluding to masculine attire in their women’s fashion collections. As well as being worn conventionally, ties were reimagined in various guises. Jean Paul Gaultier showed a dress made entirely of multi-coloured, multi-patterned neckties. Margarita Robertson of NOM*d remade men's old business and school ties into rosettes and vests to wear with her gender-ambiguous suits.

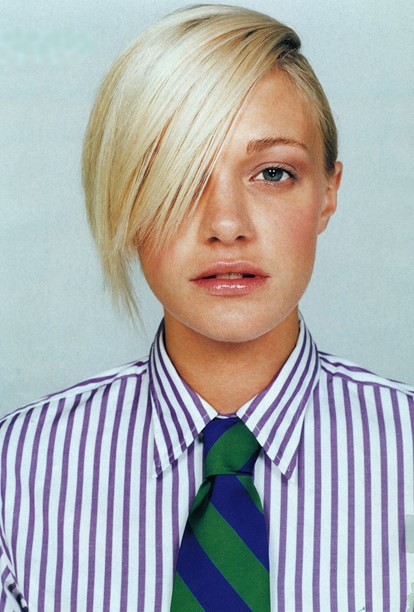

A model wears a shirt and tie in fashion editorial ‘Mad About the Boy’, Style magazine, winter 2001.

For women the tie is part of an expansive repertoire of available accessories, but for men, the tie is a staple within a much more limited wardrobe. The rising informality in dress codes and the break with traditional rules of dress has led to a far more particular interest in the tie as a key accessory. No longer obligatory, it is now more than ever a personal choice to express individual style.

Text by Kelly Dix. Banner image of Kevin Spencer from The Vault from the Evening Post 13 April 1971, courtesy of Alexander Turnbull Library, PAColl-7327, EP/1971/1574.

Published July 2019.