Stories

The Jumpsuit

1919-

Why was the jumpsuit so named? Because it was made for jumping. Out of aeroplanes. Designed as a protective garment, with skydivers (and racing-car drivers) in mind, it was introduced in Italy in 1919. In the male domain, with a few rock star exceptions, it has largely remained a utilitarian item of clothing worn for manual work, active sports such as skiing, and by members of the armed forces.

It didn’t take long for women to appropriate the style. The feminisation of the jumpsuit began in the 1920s when it appeared in a new guise – the beach pyjama. A slender all-in-one with wide, softly fluttering legs, often teamed with a bolero, a cardigan jacket or a floppy hat, it reached the height of its popularity in the 1930s.

Variations on the theme included low backs, halter necks, crossover back straps and basques, and the waist was sometimes accentuated with a narrow belt. With its wide legs, the beach pyjama gave the illusion of a long dress which probably accounts for its acceptability in a period when it wasn’t deemed proper for women to wear trousers.

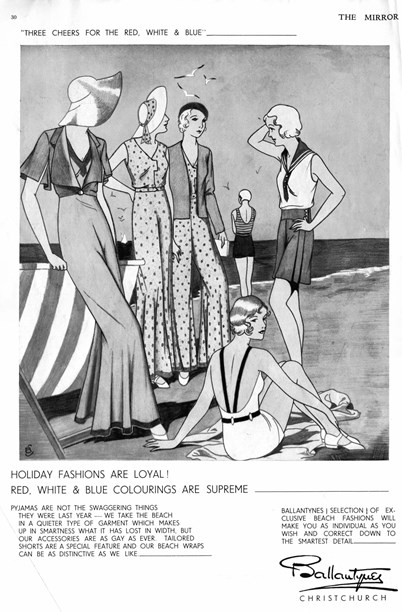

In 1932, the Christchurch department store Ballantynes, placed an advertisement for 'exclusive beach fashions' in the Mirror magazine. It stated that 'pyjamas are not the swaggering things they were last year', indicating that leg widths were becoming less voluminous.

Ballantynes beachwear advertisement, The Mirror, November 1932.

Women unable to afford store-bought pyjamas made their own. Dress patterns from the 1930s show a variety of stylish options while those from the 1940s tend to be less fanciful, conforming to the needs and spirit of the World War II years (1939-1945). No longer exclusively an item of resort-wear, the jumpsuit assumed a new role as an everyday garment.

Simplicity jumpsuit pattern, 1940s.

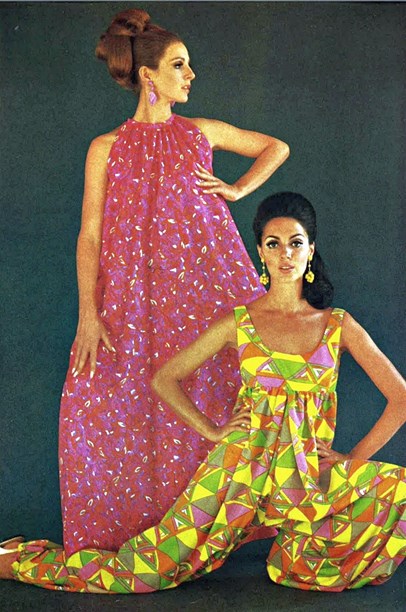

The jumpsuit faded from view in the 1950s, re-emerging in the 1960s in a new incarnation – the palazzo pant. Palazzo pants, the creation of Princess Irene Galitzine, a Russian-born fashion designer residing in Italy, were initially worn by wealthy Italians who donned them to lounge about in their palazzos (palaces), hence the name. Flamboyant in every sense of the word, palazzo pants had extremely long, wide flared legs and were usually made in brightly coloured, graphically printed fabrics.

In 1967, Vogue New Zealand, which relied on its sister publications overseas for much of its content, featured a picture of an Italian palazzo all-in-one, the pattern for which was available on request. An Auckland designer who tapped into this trend was Joan Talbot of Tarantella. The New Zealand Fashion Museum has a photo in its archive of Christine Antunovic, Miss New Zealand 1968, wearing palazzo pants, in a bold print, created for her by Joan.

Italian palazzo pants, Vogue New Zealand, Autumn/Winter 1967.

By the 1970s, more New Zealand labels, among them, El Jay, Love Story, Attic 80 by Sherwood, Yum Yum, Peppertree, Miss Deb and Roystyles for Miss Hebe, had gravitated toward the jumpsuit, with design details and fabrics varying from label to label.

Roystyles for Miss Hebe jumpsuit with high neck and self-covered fabric belt.

In the early part of the decade, the jumpsuit was adopted by the flower power fringe. Accessorised, in true 'Summer of Love' style, with headbands, tinted granny glasses and long strings of beads, it was a common sight at music festivals, love-ins and other hippie happenings.

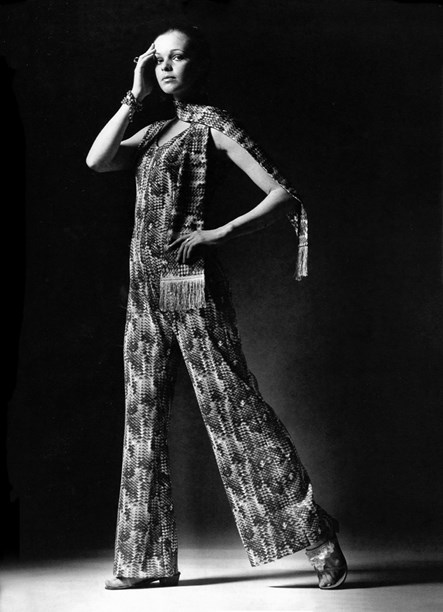

The Seventies also saw the arrival of the disco diva jumpsuit, a seductive number designed to dance and dazzle. American designers like Halston, a habitue of the New York disco scene, led the way. His halter-neck designs, cut on the bias in slinky satin crepes and jerseys, were widely copied and are still referenced today.

Miss Deb jumpsuit suitable for disco wear. The snakeskin-patterned fabric was created exclusively for Miss Deb. Model: Stephanie Overton. Photographer: Desmond Williams.

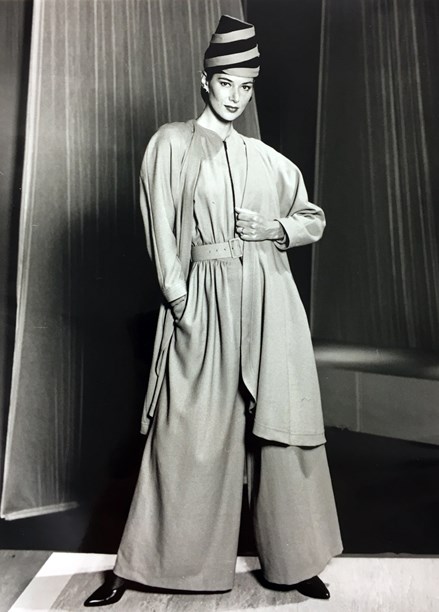

The possibility of the jumpsuit as a showstopper wasn’t lost on aspiring designers either. In the first live-to-air Benson & Hedges Fashion Design Awards, staged in Wellington’s Michael Fowler Centre in 1984, jumpsuits received nominations in three categories - Leisure Lifestyle, High Fashion Daywear and Young Designer of the Year. In 1989, the same year his Raj-inspired evening outfit won the Supreme Award, Christchurch designer Robert Gormack was also highly commended for his entry in the Wool category, a lime green wool crepe jumpsuit and matching swing coat.

Lime green wool crepe jumpsuit and matching swing coat by Robert Gormack. Highly commended in the Wool Award category, Benson & Hedges Fashion Design Awards, 1989. Model: Trudi van Zyl.

Throughout the 1980s and the next two decades, the jumpsuit appeared sporadically, not as a major fashion trend but at the whim of individual designers and manufacturers. To celebrate the 50th anniversary of Jean Batten’s solo flight from England to New Zealand in 1936, Thornton Hall produced a casual-wear range in her honour. Flying-suits in the range, contemporary adaptations of the one Jean Batten wore, also served as a reminder of the jumpsuit’s true origins.

Street Life took a walk on the wild side, designing a jumpsuit/jodhpur hybrid in boldly checked PVC. Photographed for the label in a demolition yard in 1980, it exuded an attitude far removed from that of its predecessors, the languid beach pyjama and the posh palazzo pant.

Thornton Hall’s output of jumpsuits ranged from flying-suits to party-wear. This black velvet jumpsuit was photographed for Fashion Quarterly in 1993.

In recent years, the jumpsuit has become fashionable again. But today there is no one identifiable look. Glamorous versions are appearing on the red carpet while, at the other end of the spectrum, the boiler-suit, which shares the same DNA as the flying-suit, has been reconfigured in the name of industrial chic. For the workwear vibe, read roomy, comfortable and gender-neutral.

In Britain, television has played a part in helping the jumpsuit regain momentum. When the female lead in the hit BBC sitcom Fleabag appeared recently on-screen in a black jumpsuit with cutaway shoulders, its makers, the label Love, had to rush 500 suits of the same design into production to meet the ensuing demand.

Harper’s Bazaar Bride rated the white jumpsuit as one of the top bridal trends for 2019 and showed examples by Emilia Wickstead, Stella McCartney and Dolce & Gabbana. Auckland designer Juliette Hogan, noted for her long love affair with the jumpsuit, also advocates the jumpsuit option for brides. "Jumpsuits have gone from being playful and casual," she says, "to being cool statement pieces."

Clean, classic lines define the jumpsuits in Juliette Hogan’s 2019 collection.

When it comes to evening-wear, Kate Sylvester proposes the jumpsuit as a "fantastic modern alternative" to the predictable evening dress. "Women today want to feel effortless and comfortable even when they’re dressed up. A jumpsuit provides that feeling but also total sophistication if it is made in a beautiful fabric." For the jumpsuits in her current collection, Kate has used soft silky velvets that strike a fine balance between elegance and ease.

Sorbet pink velvet jumpsuit with shirred neckline and waist. From the Kate Sylvester Frances collection, 2019.

The jumpsuit – 100 years old this year – has undergone many transformations since 1919. It continues to inspire both fashion designers and fashion aficionados alike.

Text by Cecilie Geary.

Published May 2019.