Stories

The Chemise

'THE SACK’S GONE. Here comes the Chemise. The Sack is over and in its place comes the Chemise – to wear and to laugh in but not to be laughed at.' This comment, which appeared in the Dunedin Evening Star’s Spring Fashion Supplement in September 1958, referred to the demise of the sack dress, introduced simultaneously by Balenciaga and Givenchy the previous year.

Formless, waistless and narrowing at the hem, the sack dress was much derided, although it did have its adherents. While one British newspaper wrote: 'It’s hard to be sexy in a sack', Carmel Snow, editor-in-chief of Harper’s Bazaar defended the controversial silhouette, declaring it to be 'neither sad sack nor sexless.' American women must have heeded her words. They bought the sack by the thousand. Never mind that men said they hated it, or that 'wife-dressing' - dressing to please your husband – was of the utmost importance in America in the 1950s.

In 1957, the Evening Post photographed Wellington model Josephine Brodie outside the James Smith department store, wearing a sack dress with buttoned shoulders. The look on the faces of passers-by is one of bemusement.

Whatever one’s opinion of the sack dress, it was a completely new silhouette, a transitional style that bridged the change from Dior’s feminine New Look, which had prevailed for ten years, to the unstructured fashions of the 1960s.

A straight-fronted dress with a bloused back, the chemise was a more flattering derivation of the sack. It similarly by-passed the waist, suggesting rather than defining the shape within. The fullness at the back was achieved by gathering loose pleats, inverted tucks or draped folds into fitted bands at either waist or hip level.

Rose pink rayon chemise with bow trim by Classic. Vogue New Zealand, Spring 1958.

Full-length coats and what were known as chemise suits were also designed with bloused backs, the extent of the fullness dependent upon the type of garment. On coats, designed by the likes of El Jay, Classic, Selby and Parisian Coat Manufacturing (labels Allen Barry and Frederick Paget), the blousing tended to be subtle. On jackets, worn with pencil skirts as part of a suit, or over a matching sheath dress, it was more pronounced.

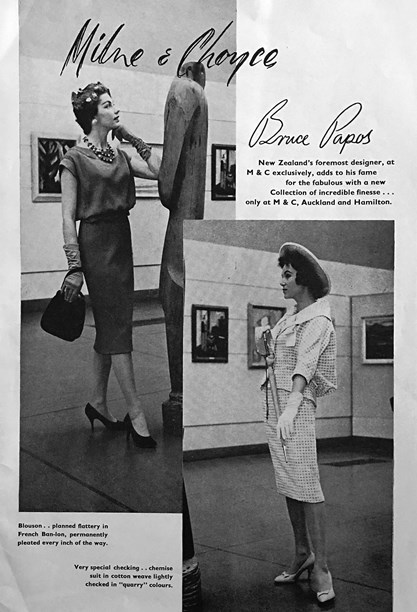

The enthusiasm with which department stores and dress shops embraced the chemise, saw the trend sweep the country, reaching beyond the main cities to smaller centres such as Nelson, New Plymouth, Palmerston North and Whangarei. It catered to all tastes and budgets. Auckland couturier Bruce Papas, for example, included chemise suits and dresses in his first ready-to-wear collection for Milne & Choyce as well as in his own haute couture collection.

Milne & Choyce advertisement for Bruce Papas dress and chemise suit in lightly checked cotton weave. Spring 1958.

The one constant with the chemise dress was the full back. Other features differed according to the maker. Cole of California, of swimsuit fame, conceived the chemise as a sleeveless sunfrock in floral printed cotton. Short sleeves, cap sleeves, double cap sleeves and bell sleeves proved popular, as did button-through backs, drop-waisted tie belts (at the back) and contrasting front panels.

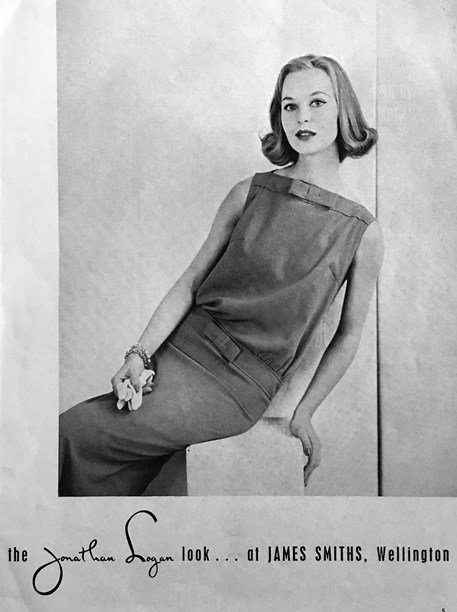

Horrockses Cottons imagined the chemise as an elongated nautical-style middy with a vertical collar and a V-neck culminating in a floppy bow. Necklines might be V, square, scooped, cowl or bateau, the latter running horizontally across the collar-bone, shoulder to shoulder. The bateau was used, to stunning effect, in the designs of the teen-dream American label Jonathan Logan, made in New Zealand under license and sold here to an equally appreciative market.

Jonathan Logan chemise with bateau neckline and bow detail. Spring 1958.

Fashion Spotting Contests, in which people on the street were singled out for their individual style, occurred regularly in the 1950s, just as they do today. A winner in Dunedin in 1958 was a Miss Meriel Canahan, wearing a cream chemise dress with an open neckline, three-quarter-length gloves and a baker-boy beret.

The accessories one wore with a chemise were as important as the silhouette itself. For their Robin Mond brand, Marler Shoes devised the 'chemise shoe', a T-bar design with a medium height spindle heel and pointed toe. The DIC produced an exclusive line of beret-like 'chemise caps' in delustred straw and strawcloth with satin or grosgrain trim.

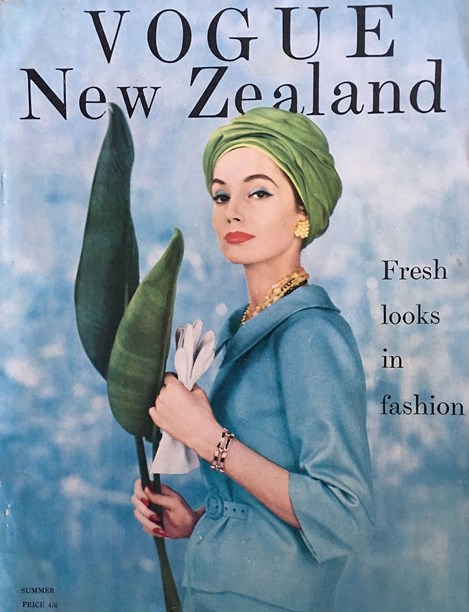

"Wherever you see a chemise or bloused back, up pops a Breton hat", observed the Evening Star. Plummer Hats did a particularly becoming version of the Breton in pastel felt, the crown bound in a contrasting grosgrain ribbon with flyaway ends. Vogue New Zealand proposed yet another chic option – the turban. On the cover of its Spring 1958 edition it teamed an olive green Dolores turban with a waterfall blue chemise suit.

Chemise suit made from a Vogue pattern, Vogue New Zealand, Spring 1958.

The suit on the Vogue cover was made from a Vogue pattern, in basket-weave Tootal cotton. By providing the pattern number and information on where to buy the fabric, the magazine encouraged readers to replicate it at home. Patterns for chemise dresses, coats and suits were also printed by Simplicity, Butterick and McCalls. The fabrics most favoured for chemise dresses and suits – mainly cotton, silk or linen – were those soft enough to facilitate back blousing. Woollen materials and French silk velvets were often selected for coats.

Chemise line patterns, late 1950s.

It would be no exaggeration to say that designers of the chemise were bitten by the bow bug. The flat bow, beloved of Jacqueline Kennedy a few years later, was the decorative detail du jour. Strategically placed, back and front, on dropped waist-bands, shoulders and necklines, its flatness suited the chemise’s angular lines.

At the same time they were lauding the chemise, newspapers and magazines were talking up 'the next big thing' – the trapeze line, designed by Yves Saint Laurent for his first Christian Dior collection in 1958. British Vogue described the trapeze, which flared gently from narrow shoulders, or just below the bust, to a wide hemline, as 'the backbone of the collection.' El Jay’s Gus Fisher, licensed to make line-for-line reproductions of Dior originals in New Zealand, responded quickly. A grey and white spotted silk trapeze dress signed El Jay for Christian Dior, appeared in the 1958 Spring edition of Vogue New Zealand. A soft, loosely tied bow marked the high-rise waistline, the skirt was gently gathered.

Silk dress in a trapezoid shape by El Jay for Christian Dior. Vogue New Zealand, Spring 1958.

The sack, the chemise and the trapeze provoked comment and excited the imagination in equal measure. But their most significant contribution to fashion was that they were catalysts for change.

Text by Cecilie Geary. Banner of a 3-figure sketch from Arthur Barnett ad, September 1958, Evening Star.

Published December 2019.