Stories

The 1970s Fashion Revolution

1970s

Flared trousers, platform shoes, hand-painted muslin tunics, crushed velvet dresses, embroidered jeans and shirts, long hair, op-shop frocks, kaftans, empire line dresses, skinny rib tank tops, aviator sunglasses, peasant skirts, unisex t-shirts: all were part of the visual landscape in 1970s New Zealand.

Whether these things make you cringe or awaken a happy nostalgia will depend upon your age and where you were in the 1970s. If you were young, optimistic and embraced the era as the dawning of the Age of Aquarius you will remember this decade as a dynamic time of change when the conservative social status quo was being loudly challenged. Many questioned the values of the prevailing post-war culture with its aspirations of a comfortable, suburban, consumerist society and this decade saw the rise of women's liberation and the ascendency of countercultures.

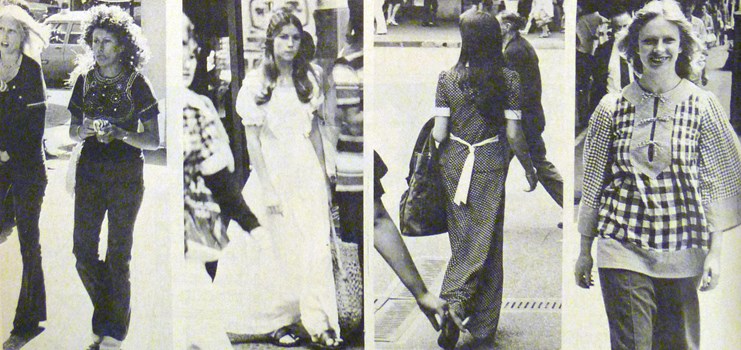

Photos from the Eve magazine story 'What people are wearing - summer in the cities'. Photographer unknown. All Rights Reserved, Eve magazine.

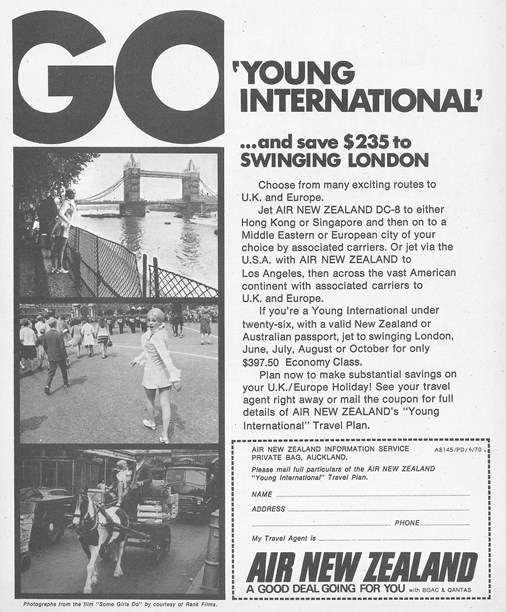

What was New Zealand like at the dawn of this new age? Over the two prosperous preceding decades, the population of New Zealand had increased by over one million people and in 1973 reached three million. Britain was finally reconciled with Europe and entered the European Economic Community (the precursor to the European Union) which undermined our secure economic status as 'Britain’s farm'. The oil shocks of 1973 (and 1978–9) further highlighted the vulnerability of the New Zealand economy. At the same time colour television arrived here, signalling the pervasiveness of that medium, which now brought world news and its powerful images into every home. Jet travel became more affordable and hence more available. Air New Zealand now flew all the way to London, making overseas travel (or the 'Big OE') not only possible, but almost obligatory for the young and unencumbered. Air New Zealand and BOAC offered special 'Young International' airfares to Swinging London for those under the age of 26 for only $395.50; this when the average weekly wage was $95. All in all, those who came of age in the 1970s were looking beyond the limitations of their parents' generation and cultivating a much broader and more nuanced world view.

Ad for Air New Zealand's 'Young International' airfares to London, 1970.

Young people born into post-war prosperity, the so-called baby boomers, were beneficiaries of the ensuing economic expansion. The welfare state and economic protectionism ensured that they were well fed, housed and educated regardless of their parental income. There was no need for them to go out to work at a young age in order to contribute to the family income, as many of their parents had done. Instead they could enjoy the pleasures and freedoms of their status as teenagers, able to choose between accessing a virtually free tertiary education or earning an income. The triple luxuries of time, education, and an income of their own gave them enormous freedom to engage with the world, but also to question the values of their parents. Some wondered if the nuclear family was a sustainable living model or whether it consumed too much of the earth's resources.

Young women were asking why their future lives should be restricted to child-rearing and home-making, and why, when they did enter the workforce, they were being paid less than their male counterparts. Young men were asking why we were fighting in an American-led war in Vietnam, and why they should be conscripted for military training in the first place.

Māori marched to Parliament to call a halt to the continuing loss of their land and assets. Pacific Island youth protested racial discrimination and the marginalisation of their people. Many questioned whether we should play rugby with a nation that practised apartheid, a system that was anathema to our image of ourselves as a racially-integrated country.

Māori land march demonstrators walking along the motorway in Wellington, 1975. Photo by Christian Heinegg, courtesy of Alexander Turnbull Library, Ref PA7-15-08.

People of both genders and many ethnicities questioned how safe the testing of nuclear weapons was, if the French needed to do it in our Pacific neighbourhood, rather than in their own backyard. And within our own borders many decided that they were not prepared to sacrifice our natural environmental assets, including the pristine shores of Lake Manapouri and Lake Te Anau, in order to provide cheap electricity that would generate profits for a foreign-owned aluminium company. Not only did we ask these questions, but we took to the streets to demand answers. People were looking for new values and a better way forward.

Pro-abortion march in Wellington, 1973. Photograph taken for the Evening Post newspaper by an unidentified photographer. Image courtesy of Alexander Turnbull Library, 1/4-021373-F.

Briefly New Zealand had a government – and a Prime Minister in Norman Kirk – who shared these concerns and appeared to be listening. The Labour Government, elected in 1972, introduced the Ohu scheme to support groups who wanted to live in kibbutz-style communities. The New Zealand troops were brought home from Vietnam, the Springboks were uninvited to come and play rugby here and the government sent a naval frigate to Mururoa Atoll to protest the French nuclear tests. Kirk's sudden death in 1974 put an abrupt end to this brave new world, but we were learning fast that we needed to look to ourselves and to our own capabilities and resources for our future well-being both at home and in the world.

Some of the social issues at the forefront in the 1970s, like concern for the environment, found form in the fashion of the day. Natural materials like cotton and silk became a popular fashion choice again and there was a focus on recycling and upcycling vintage clothing. The era also saw a dynamic handcraft revival with techniques such as textile dyeing and printing, knitting, weaving, applique, macrame, and ceramics being embraced creatively to customise and produce one off pieces. These handmade pieces found their customers at weekend markets, in emporia and in quirky back street boutiques.

A revival of one-off, handcrafted garments represented a growing social movement concerned with protecting the environment and living naturally.

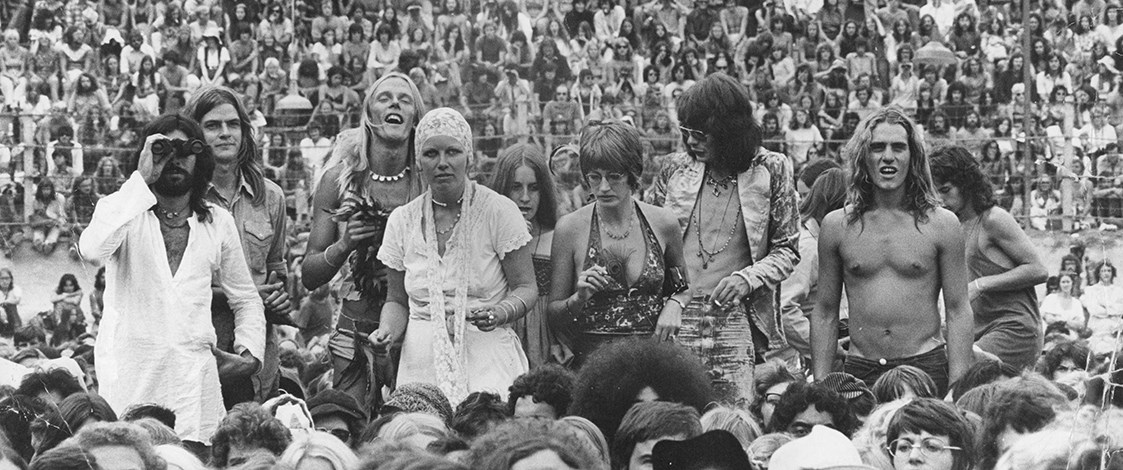

Perhaps the fashion trend that most clearly articulated the aspirations to liberation was the ascendency of the unclothed and unharnessed body. Nakedness became a regular sight at music events and other outdoor gatherings and even in more urban settings a bare chest or unrestrained breasts under a t-shirt or a dress warranted hardly a second look.

Nambassa, 1979. Photo by Bruce Connew.

This freedom translated into the fashion of the day for both men and for women where the 1970s silhouette was natural, fitted to, or gently flowing over the body's contours. The shoulder fit was soft and slim, with a narrow upper torso which filled out, flared or floated to the hem of the sleeve or the lower edge of the garment. The shapes are reminiscent of the 1930s with their emphasis on halter necklines, empire line seams and languid lengths, and the addition of soft floppy hats, feathers and furs.

The 1970s silhouette with a soft shoulder and flowing length. Garments by Hullabaloo, Peppertree and Bendon.

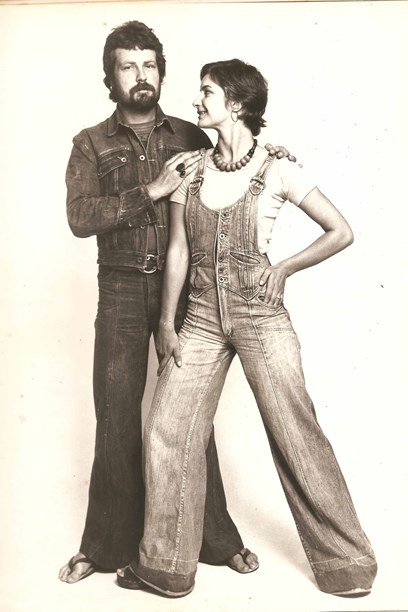

Pants too were a defining garment of the 1970s and common to both genders. While women had worn pants before when necessary for sport or work, they were not an acceptable urban garment for women until the arrival of the pant suit in the late 1960s. Conventional society saw trousers as unfeminine, which meant that wearing them, and indeed freeing up the dress code as a whole, became a political target for the flourishing feminist movement. Just like the wearing of a bra, normative dress codes and conventions were seen as oppressive for women, restricting them physically and constraining their ability to partake fully and freely in society. Wearing pants – and most especially wearing flares over platform shoes, which accentuated the length of the leg – exaggerated the effect of this newly claimed freedom. Flares might have been a pair of Boss Bella Bravas from Keans, or they might have been sewn by Mary-Jane O'Reilly for her Black Sheep label and bought at Cook Street Market. Whatever your budget, gender, or age, in the 1970s you would have owned at least one pair of flares.

Black Sheep denim flares were sold at Cook Street Market. Image © MaryJane and Phil O'Reilly.

Increasingly too the New Zealand lifestyle was becoming more individual and hence more diverse with a new orientation towards clothing that was more casual and comfortable. The 'separate' came to represent that flexibility and its rise allowed for many and varied combinations that could be adapted to suit any occasion. But whether following a tailored or a hippy aesthetic, the trapeze shape is the predominant geometry of the decade: bell bottoms and bell sleeves, halter-neck tops and A-line skirts. No matter what your preference – peasant skirts and Danish clogs, safari suit and an open neck shirt, psychedelic print kaftans, or nothing at all – by the end of the era it was widely accepted that different styles could co-exist and what was important was that you should choose clothes that expressed your individuality.

Text by Doris de Pont. Banner image of Rachel Stace and friends at the Rolling Stones concert in 1973. Photographer unknown, image originally published in Craccum magazine.

Published June 2021.