Stories

Rosemarie Muller

1924-2018

Rosemarie Muller was born in 1924 in The Hague, the political capital of The Netherlands, to an Austrian-born lawyer father and mezzo-soprano mother. She was the eldest of two children. Both her parents were well-educated, multi-lingual and well-read.

Rosemarie inherited an early interest in sewing from her mother, who she remembers as being a very good dressmaker as well as an excellent cook. While she enjoyed sewing, she never considered it as a career prospect until much later.

In 1951 Rosemarie married Harm Muller, the son of a senior executive at the Royal Dutch Shell company (commonly known as Shell petroleum). After their marriage Rosemarie and Harm lived on the uppermost floor of the Muller’s spacious house in The Hague while they saved for their future.

The same year as her marriage, Rosemarie booked a place for herself and her sister-in-law Connie in an intensive haute couture sewing course. She recalls that the highly popular six-week-long course was hard to get into and had to be booked well in advance. It was tutored by a French national who was haute couture trained and worked in the fashion industry in Paris. Rosemarie’s understanding is that the woman visited Holland annually with her Dutch-born husband to visit his family. Following her successful completion of the course Rosemarie began to design and make clothes for herself, for family and for friends.

The immediate post-WWII period, following occupation by Germany, was a difficult time for many Dutch people. The Netherlands’ economy was in ruins and there was high unemployment and housing shortages adding to the general malaise. With their homeland in ruins, huge numbers of Dutch people contemplated emigration. Rosemarie and Harm were amongst those keen to move away and start a new life in a different country.

After successfully trialing small numbers of Dutch migrants from 1945, an agreement between The Hague and New Zealand in 1950 encouraged the emigration of skilled migrants. Others arrived through the New Zealand Assisted Passage Scheme or, like Rosemarie and Harm, by paying their own way.

Rosemarie and Harm had set their sights on New Zealand after meeting up with friends at a bridge party who were about to emigrate there. Harm’s father, eager to have his son follow in the family business, tried to persuade the couple to move to Mexico where Harm could be assigned a position in Shell’s offices there, but the couple decided upon New Zealand nevertheless, despite the lack of such employment prospects. They arrived in Wellington in 1952.

New Zealand legislation required Rosemarie and Harm to have their accommodation organised and restricted the amount of money they could bring into the country (75 pounds each). Rosemarie and Harm planned ahead by ordering a prefabricated home before leaving The Netherlands, and having it shipped in crates to Auckland.

While they waited for their home to arrive, the couple spent three months in Wellington. To makes ends meet, Rosemarie put her new skills to good use and quickly found a position as a machinist, one of three, for a small garment producer. While she didn’t work there very long - only "a few months" - Rosemarie recalls that she picked up a lot of very useful commercial sewing tricks of the trade, improved her skills on an industrial sewing machine and garnered a little understanding of the garment manufacturing industry, skills that would prove very useful when she eventually set up her own business in Auckland.

With the arrival of their house imminent, Harm and Rosemarie moved to Auckland where they purchased a sizeable plot of land in Titirangi (that included a running stream) and cleared a driveway down to a secluded site surrounded by lush native forest. Having only ever lived in The Hague, Titirangi seemed like a tropical paradise.

Harm found a job at the Auckland port while Rosemarie started dressmaking, at first for friends and then for more people as word spread about her ability and natural flair for fashion.

Rosemarie Muller in the 1960s.

To accommodate Rosemarie’s growing clientele, the Mullers excavated the slope beneath their home to create a ground floor. Incorporating a workroom and a showroom, the new space allowed Rosemarie, at least physically, to separate work and family.

Rosemarie’s earliest business model was to maintain a rack of finished garments, all designed and sewn by her. As demand for her garments increased she recruited her first employee - another Dutch immigrant - a woman who, while not a trained machinist, was very good at sewing. Eventually Rosemarie would employ more machinists and two cutters to free her up for designing and dealing with clients. By 1993 she employed five people in her workroom.

Until she established her own retail boutique in the 1980s, Rosemarie operated mainly as a wholesaler, her main clients comprising department stores and exclusive fashion boutiques. Her first major client was an exclusive Auckland fashion boutique called Flair which was located in Vulcan Lane, home of some of Auckland’s most elite fashion stores. In 1958, Flair was described in Vogue New Zealand as "an exciting little boutique which seems to have absorbed the very atmosphere of fashion..." The ‘Shop Hound’, Vogue’s reporter on all things new in the way of shops and products, also mentions ‘imaginative window displays’ and the store’s "wonderful collection of day, afternoon and cocktail frocks".

Rosemarie was pleased for her garments to be carried by Flair. Being represented in such an exclusive store provided her with entrée to the buyers of New Zealand’s best department stores such as Smith & Caughey's in Auckland and Kirkaldie & Stains in Wellington. By 1958 it was reported that Rosemarie supplied "a Dominion-wide market".

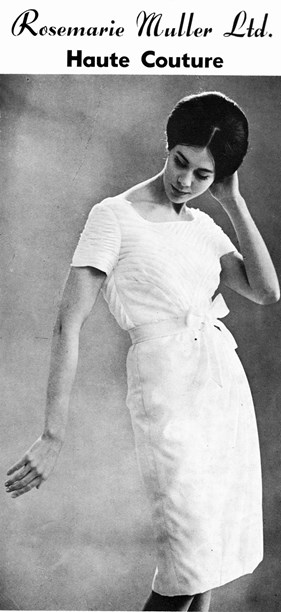

During her 30 years as a wholesaler, Rosemarie had no need to advertise. One of the very few advertisements from this period of her career appeared in Vogue New Zealand in 1959. It may have been prompted by her placement (2nd) in the inaugural Gown of the Year competition in 1958, a high profile event that "provided unprecedented exposure, bringing to national attention unsung regional heroes and launching several highly successful careers in the design industry".

Featuring a photograph by Ted Mahieu, the advertisement depicts a mannequin posed in Rosemarie’s Titirangi workroom, a striking juxtaposition of high fashion and workspace. The model, Rosemarie’s favourite, Else van den Muysenburgh, wears a luxurious and superbly fitted strapless heavy silk satin evening gown featuring oblique swathes of fabric to the bodice (forming one draped sleeve) and to the hip (falling to form a loose panel). Her business is described as Rosemarie Muller Haute Couture, representing one of the earliest uses of this French term in the New Zealand fashion press to describe New Zealand-made high fashion garments.

Rosemarie studied the traditional French haute couture method of garment construction during an intensive dressmaking course in Holland.

The resulting publicity from the Gown of the Year competition undoubtedly prompted the two-page profile on the designer that appeared in the October 1958 issue of The New Zealand Woman’s Weekly. Describing Rosemarie as "tiny, bustling, [and] businesslike with a quicksilver beauty that makes you nervously aware of the static nature of photographs" the unnamed author provides valuable contemporary (albeit brief) insight into the designer’s fashion practice.

We learn for example that Rosemarie creates "on the stand" in true high fashion style, a reference to the French technique known as draping. "None of her evening gowns is duplicated. She knows the feel of the materials she will use and while she is 'fiddlin'” around on the stand ... she twirls, tucks and pins book muslin or calico into a creation. Once the idea for the gown has crystallised she works with the actual material and finishes the gown on the stand." This traditional French haute couture method of garment construction was taught to Rosemarie during the intensive dressmaking course she completed in Holland.

Rosemarie Muller rarely advertised her label. This advertisement appeared in the programme for the 1963 Golden Shears Awards.

For out of town buyers used to doing their business in Auckland’s city centre, where Rosemarie’s contemporaries such as Emma Knuckey and Babs Radon had their salons, getting to see Rosemarie Muller’s collections presented more of an adventure. Twice a year Rosemarie would spend days picking up buyers from their city hotels, conveying them in style in her MG convertible to her Titirangi showroom where they were wined and dined and given private showings of her latest creations. Rosemarie’s first house model was Else van den Muysenburgh, a fellow Dutch migrant who arrived in New Zealand in 1952, the same year as Rosemarie and Harm.

In an interview with North and South magazine in 1993 Rosemarie spoke about her love of designing and pattern making, both of which were her fortes. "I never learned to pintuck or topstitch, but designing and patternmaking I love. Most of all I like the creative work, dreaming it up and seeing it made."

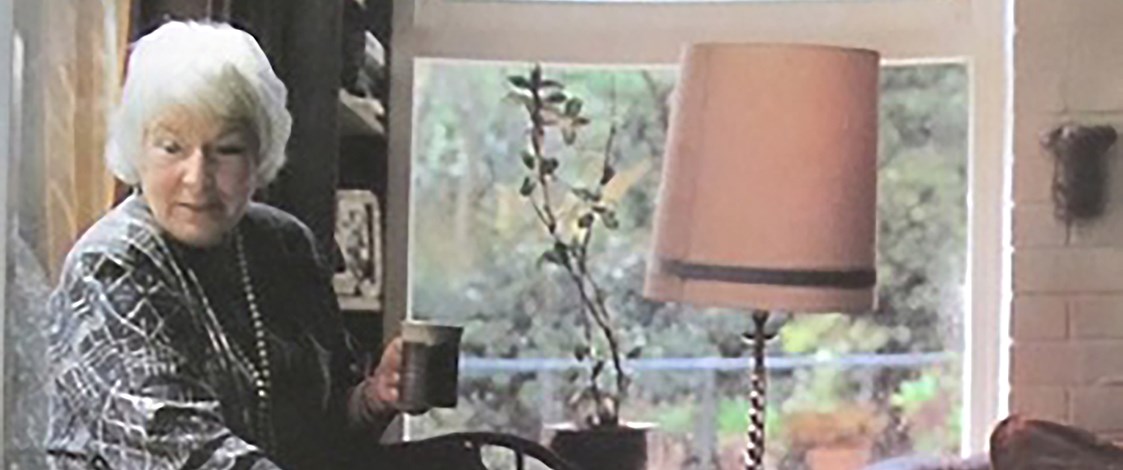

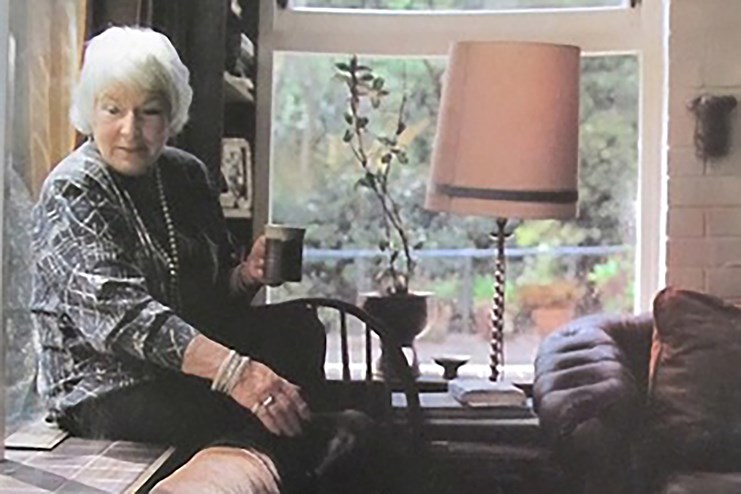

Portrait of Rosemarie Muller in North and South magazine, 1993. Photo by Ralph Talmont © Bauer Media.

At the time of the North and South interview Rosemarie was particularly enjoying a stint designing "beautiful blouses in hand-painted silks". The use of high quality exclusive textiles has always been a hallmark of her style. While she occasionally used prints, she preferred working with high quality natural fibres - silk, linen and wool - in plain, saturated colours. She was very fond of firm regally beautiful silks such as silk duchesse satin, which she fashioned into cocktail and dinner gowns and other forms of formal evening dress. These gowns would often feature subtle hand beading, which was carried out in her own workroom.

Rosemarie recalls that in order to get exclusive New Zealand rights to a particular fabric, she had to purchase ten yards of it. She might get two garments from it - a suit and a cocktail gown for example - and, to retain the exclusivity, she ensured they were never wholesaled in the same city. Her most exclusive fabrics were purchased from visiting international textile merchants or their Auckland representatives. Beautiful distinctive buttons often featured on Rosemarie’s garments. These were often a family affair with her daughter helping her hand make buttons in fabric matching the garment.

In terms of style, Rosemarie Muller could be called a classicist. She liked her garments to acknowledge major international fashion trends but never fads. Her clients purchased clothes as an investment in style that stood them in good stead for a number of years, rather than a season.

Along with her peers, Rosemarie would on occasion be approached to work on special commissions: a wedding dress for up and coming barrister (Sian Elias), or formal garments for the wife of a Governor-General. Rosemarie is proud to have designed gowns for the wives of three Governors-General including Lady Kathleen Porritt and Lady Norma Beattie.

In 1984 Parnell’s sartorially rich main road boasted a new boutique. Encouraged to join the rich mix of fine dining, fine art and sophisticated fashion by Parnell village founder Les Harvey, Rosemarie Muller finally opened her first, eponymous, shop.

Retailing her own garments, imported accessories (scarves, for example) and, for a few years, a range of high-end knitwear hand knitted by outworkers, Rosemarie ran a successful fashion business until 2007, when she closed the Parnell store, ending a fashion career spanning more than 50 years.

Still active until her early 90s, Rosemarie spent her retirement gardening, improving her French, and being a hands-on grandmother to her five grandchildren.

Text by Angela Lassig.

Last published October 2018.