Stories

Jane Mabee

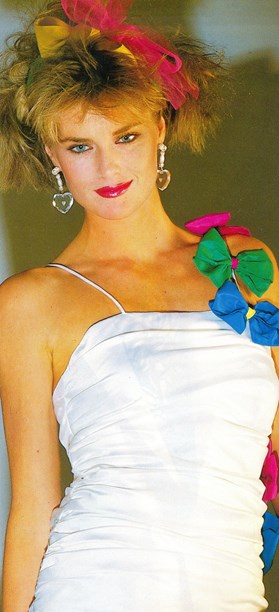

Designer Jane Mabee’s first recollection of anything to do with fashion was showing a little friend how to tie a bow. "I couldn’t have been more than five and I have no idea who taught me. Along the way, bows became my unintended trade-mark.

I remember Fashion Quarterly publisher Don Hope asking me once, for an article in the magazine, to please explain why I put 'those' bows on everything."

Betsy Ruff white silk dress with coloured silk bows, 1985.

Courtesy of her mother’s dressmaker Mrs Higginson, Auckland-born Jane began as a small child to drape and pin scraps of fabric on her dolls. "It was all about the clothes, never the dolls," she says. "I would fiddle about with fabric and amazing colour combinations for hours." Sneak peeks at her older sister’s Seventeen and Honey magazines and her mother’s Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar magazines further stimulated her interest.

Recalling her secondary schooldays, Jane says the words she was most drawn to when she started learning French were those with fashion connotations – tissu, couleur, couture, prêt-à-porter, crepe de chine, ombre, Rue St Honoré, Avenue des Champs-Elysées ... And she remembers trimming a red polka dot shift she made in sewing class with white ric-rac braid.

In 1972 and 1973, Jane attended the Wellington Polytechnic School of Fashion. She admits to being a "random student", just skimming through by the seat of her pants. Her lack of diligence did not prevent her from being one of only about 12 students from an initial intake of 80 to graduate with a full diploma in clothing and textiles. To this day, she regrets having paid little heed to the Menswear Course. "We had a wonderful tutor who had been a tailor on Savile Row. I could have learned so much more from him."

Of her first job as a patternmaker in the workroom at London Affair, a Swinging London inspired boutique on Auckland’s Queen Street. "It was all peace, love and mung beans,” she recalls. Based on the prevailing trend for hippie garb, London Affair turned out caftans, bell-bottoms, ten-gore skirts, granny prints, lots of applique and t-shirts with cap sleeves. When the business’s owner Nado Dean shut up shop in 1975, Jane, having become involved in the design process, bought his workroom equipment and set up her own workroom and label which she called Betsy Ruff. She was 21.

Tempted to give her label a French name, Jane was put off by the fact that Chez Bleu, a Queen Street denim boutique, also owned by Nado Dean, was commonly mispronounced as Chez (as in fez) Blue. One of the main reasons she chose Betsy Ruff, she explains, was because it was easy to say. "I found the term in my History of Costume textbook from design school. The small ruff called the Betsy was a fashion revived in the 19th century from Elizabethan times." Many people thought Betsy Ruff was Jane’s actual name.

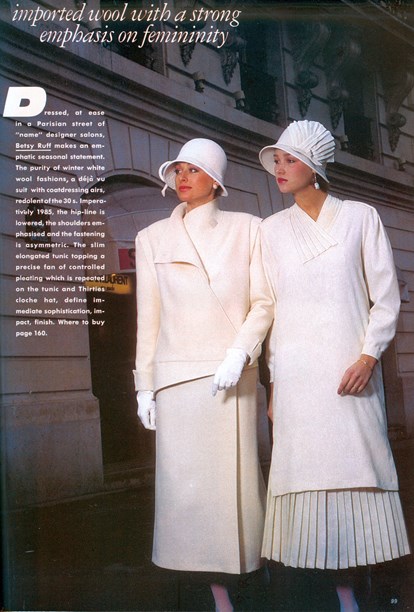

Working with luxurious fabrics, Jane produced city suits, coats and dresses with innovative design details such as subtly controlled pleating, unexpected pocket placement and asymmetric closures. She also designed clothes for special occasions. Among her first retail clients were Carters in Wellington and Kristen Boutique in Auckland. Keen to expand her wholesale operation, when Fashion New Zealand (later Fashion Quarterly) began publication in 1980 she checked out the list of retail stockists at the back of the magazine, selected those she thought appropriate then travelled the country drumming up new business. Betsy Ruff featured regularly in the early Fashion New Zealand/Quarterly fashion editorials. Although still in its infancy, the magazine was fast becoming the place to be if you wanted your fashion credentials to be taken seriously.

Betsy Ruff winter whites, Paris fashion shoot, Fashion Quarterly, winter 1985.

In 1983, Jane opened the Betsy Ruff boutique on Ponsonby Road in Auckland. "Ponsonby really was the Wild West in those days," she says. "But I could see that although it was run-down, creative studios and shops were beginning to appear along the strip. Besides, I’d always flatted in and around the area so it made sense to work and live in the same neighbourhood." The building, erected around 1900 and a paint shop for many years, was in a pretty dire state. It took a few months to renovate but finally opened, with "quite a bit of fanfare", to a receptive customer base Jane had been building over the previous years with her wholesale business. With a workroom on the premises, and a staff of six, Jane was now able to offer a made-to-measure service in addition to her seasonal collections.

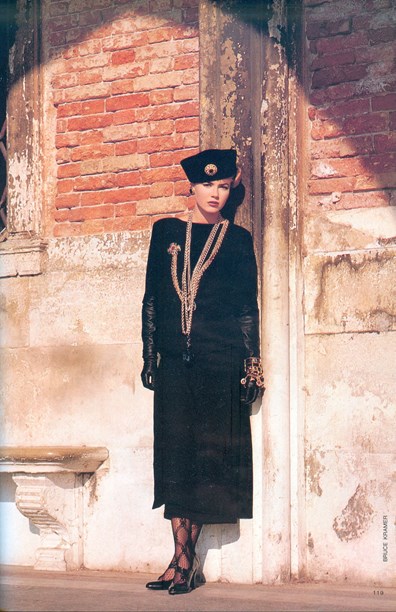

Betsy Ruff black wool dress, Venice fashion shoot, Fashion Quarterly, winter 1986.

Former Miss Universe Lorraine Downes was among the many brides who walked down the aisle in a Betsy Ruff creation. Jane also designed Lorraine’s outfit when she returned to the United States to judge the Miss Universe Contest the year after her win in 1983. The dress, a black sequinned sheath, had Elizabethan-style sleeves of hot pink and emerald green Thai silk. As Lorraine was to be seated during the judging, Jane specifically focused attention on the dress from the waist up, a tip she picked up from Italian-born couturiere Elsa Schiaparelli who adopted the same approach in similar situations.

Highly Recommended in the Casual Daywear, High Fashion Daywear and Outstanding Evening Garment categories in the 1982 Benson & Hedges Fashion Design Awards, Betsy Ruff won the After Five High Fashion Award in 1984 with 'Black Magic'. An extravagance of black silk organza, the winning gown had a cleverly constructed asymmetric top and was worn with a wrap lined in peony pink Thai silk.

‘Black Magic’, the Jane Mabee dress which won the Benson & Hedges After-Five High Fashion Award in 1984.

An invitation in 1983 to represent New Zealand at a fashion spectacular in London, celebrating the 200th anniversary of the famous fabric Viyella, saw Jane’s designs modelled alongside those of Givenchy, Versace, Ralph Lauren and other international designers.

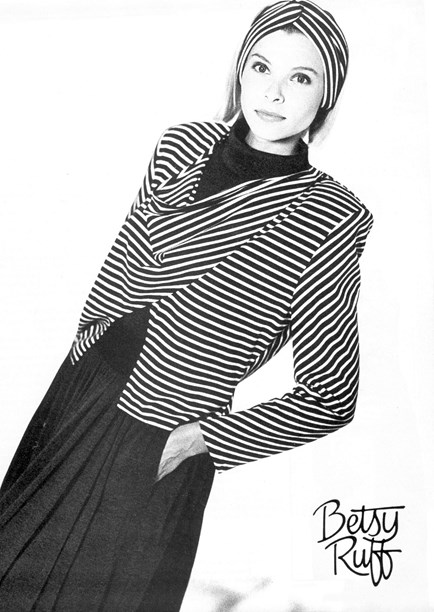

Betsy Ruff advertisement, 1989. Image © Jane Mabee.

As a result of a downturn in the economy in 1991, Jane closed Betsy Ruff and set up Filigree, a smaller operation specialising in one-off couture pieces for individual clients. During this time, she employed sometime fashion designer and all-round creative talent Perrin McLeod - "a wonderful and clever man whose tailoring was sublime".

From 1994 until 1998, Jane headed the womenswear design team at Ambler & Co, traditionally makers of men’s shirts.

Back on her own in 1998, Jane created Paperwhites, a line of white 'dress' shirts made from Swiss cotton organdie, Italian and French silk and quality Japanese cotton shirting. Embellished with fine laces and crystal and pearl buttons, the shirts wholesaled successfully in New Zealand and Australia until after the 9/11 terrorist attacks when a significant drop-off in Australian orders forced the business to close.

In 2002, Jane was approached by Robyn Hall of High Society Fashions, home of the Obi and Catalyst brands. She started a new label for Society Fashions - targeted at the plus-size market. Chocolat, named after the movie starring Juliette Binoche and Johnny Depp, became the fastest growing brand in the company’s history. Jane says she enjoyed the challenge of making women with curves look chic and feel fabulous. "What it came down to was the art of optical illusion. The cut, the colour and choice of fabric were paramount considerations."

Jane Mabee for Chocolat by High Society.

Head-hunted in 2013 by an Australian company to start a special occasion plus-size label for the British market, Jane crossed the Tasman. Although the 'dream job' didn’t work out, the move to Melbourne had its compensations on a personal level. In November 2015,wearing a dress inspired by an Alexander McQueen design in the China Through the Looking Glass exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 2015, Jane Mabee married retired Australian entrepreneur Noel Murphy and decided to take early retirement.

The couple divide their time between their home in Melbourne and their second home, an apartment in a 14th century castello (castle) in Bolsena, north of Rome. As for any future involvement in creative activities, the fashion veteran of 41 years doesn’t rule it out.

Text by Cecilie Geary. Banner image © Jane Mabee.

Last published March 2016.