Stories

Fashion Photography in New Zealand

1930-2015

At first glance a fashion photograph is simply a model dressed in beautiful clothes. But take a closer look and the construction of the image is exposed. It is a fantasy created by the setting, the stylist, and of course, the photographer.

Fashion photographers are prolific image makers. They trade in the production of desirable and aspirational pictures that convince the audience that the projected look and related lifestyle is possible - if only they buy the dress/shoes/lipstick. The success of the image relies on its ability to resonate with the viewer. The photographer presents us with a mirror, albeit a rose-tinted one, that allows us to see ourselves as we would like to be seen.

Fact and fantasy

Although an image has a commercial purpose, that does not exclude it also having social, cultural and artistic value. A review of more than eighty years of New Zealand fashion photography allows us to see how our society and identity has changed; how we see ourselves and what we value. Because fashion is synonymous with newness and change, its photographers have always been leaders in cultural reproduction and advancement.

Photograph for Silknit lingerie, 1940s, courtesy of Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, 34-D270K.

Our geographical isolation has nurtured a particular 'New Zealand-style' of film, music, art and design. This is true also for fashion photography. While international magazines such as Vogue and i-D have a broad global reach and must cater to very diverse consumers, New Zealand magazines target specific local audiences.

Marissa Findlay photographs for the editorial 'If you could read my mind', Black magazine, issue 19. Image © Marissa Findlay.

Although not isolated from global trends, this restricted focus has given our photographers an opportunity to cultivate a unique local identity by capturing, generating and giving back the desires and lifestyle aspirations of each particular generation.

Photograph by Stephen Tilley. Image © Stephen Tilley.

In the studio

Fashion photography began in the studio - an environment where light could be controlled. Today the studio remains the first choice for Auckland photographer James K Lowe, who prefers to simulate outdoor light than deal with the harsh and unpredictable reality of it. "The sun is a single source of light with so many variables. To me it’s so much easier to add light than to try take it away," James says. Inspired by a campaign with Huffer where he witnessed his sketches transformed into a studio space, James now uses the studio as a place of experimentation. He bought a nail gun and started learning the art of set building, using props and lights to create constructed environments for his images in much the same way his predecessors did.

Publicity photograph for Berlei underfashions, circa 1930 by Gordon Burt. Image © Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Photograph by James K Lowe for twenty-seven names, 2016. Image © James K Lowe.

In the early 20th century, when the medium was still in its infancy, fashion photographs were often static, lifeless pictures, due to the long exposures needed to capture a clear image. A long history of painted portraiture also influenced the staged style of early photography.

Photograph by Herman Schmidt for Milne & Choyce, circa 1910. Contact Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries, 31-AD13-2 for copyright details.

The photographer's objective was to depict a real garment on a model so that it could be reproduced in print. The poor quality of early black and white photographs, however, meant that they often compared unfavourably when placed alongside the detailed and brightly coloured pictures that were created by the talented fashion illustrators of the time.

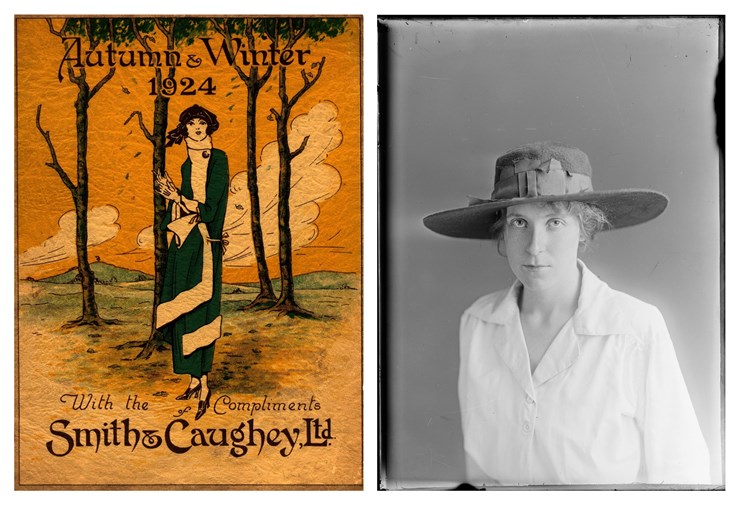

Legibility of the photographs printed in magazines and catalogues relied on detailed captions. The July 1922 issue of The Ladies Mirror featured photographs by Robert Henry Bartlett and Herman John Schmidt. Glamorous models wear garments from the department stores Milne & Choyce, John Court Ltd and Smith & Caughey’s.

Illustration for the Smith & Caughey's Ltd catalogue, Autumn/Winter 1924 (left) and fashion photographs for The Ladies Mirror, July 1922.

The descriptive text provided the detail missing in the grainy reproductions - the words carefully chosen to enhance the fantastical images. "Cut on semi-classical lines is this frock of jade broché cashmere de soie. The offering to Bacchus, in the shape of a cluster of beautiful panne velvet grapes and foliage gracefully attached to the waist, is very effective, especially when repeated in the dainty head-dress." (The Ladies Mirror, July 1922).

The coming-of-age of fashion photography corresponded with the rise of consumerism. The surge of new products were promoted by increasingly sophisticated advertising. Photographers were in demand to create appealing images of the latest fashions and the newest technology.

By the 1930s, Wellington photographer Gordon Burt had a large portfolio of commercial clients, including Berlei, Prestige Hosiery, Canterbury, Bonds, Sincerity Suits, Roslyn and Jockey. Most of his photographs were taken in the studio with one or two models posing with props such as classical statuary, chairs and small tables.

Photograph by Gordon Burt, 1928. Contact Alexander Turnbull Library (Ref. 1/2-037044-G) for copyright details.

In Auckland, Clifton Firth had established a photography studio with his wife Patricia. Clifton was a trained graphic designer and his photographic style was influenced by the Bauhaus design conventions that were being used in cutting edge New Zealand print advertising at the time. Glamorous black and white Hollywood studio portraits - which used a dramatic blend of light and dark to enhance and flatter the subject’s features - also coloured his style.

Photograph by Clifton Firth for Milne & Choyce, 1939. Contact Sir George Grey Special Collections 34-M7B2 for copyright details.

Several decades later, Desmond Williams also abandoned his plans to be a graphic designer and picked up a camera instead. He had moved to London in 1959 where he was studying art and working part-time as a design assistant to Barry Trengrove, the art director of Harper’s Bazaar. A chance meeting led to a photographic assistant position with acclaimed fashion photographer Terence Donovan. Here Desmond honed his skills before eventually returning to New Zealand in 1966 where he quickly made his mark as a photographer for Vogue New Zealand. Wellington photographer, Sal Criscillo, recalls the impact that Desmond had on the industry. "Young local photographers were starting to develop an awareness of fashion as portrayed in English and American magazines. They were looking at model poses, lighting and so on and Des was a big part of that. What others were reading about, he did. When it came to implementing new photographic techniques, again Des was always two steps ahead."

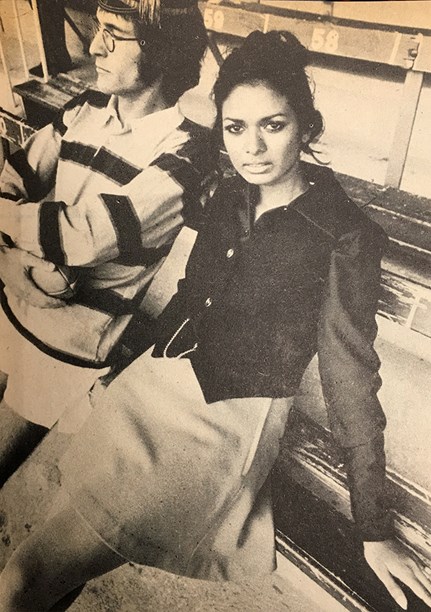

Photograph by Desmond Williams for New Zealand Vogue magazine, Spring 1966. Image © The Condé Nast Publications Ltd.

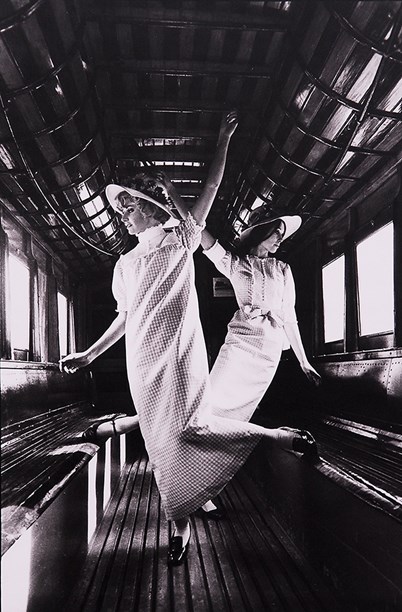

Photographic techniques weren't the only London influence at this time. Model poses, framing and the setting changed immensely during the 1960s.

On the street

Photographers headed outdoors as the setting became a key player in the construction of the fashion image.

When fashion photographs were intended simply to show off the clothes, an exterior location was seen as a distraction. But as marketing became more sophisticated, fashion became inextricably linked to lifestyle. The setting now joined the garment and the model as a key player in the story of a photograph.

Photograph of Judith Baragwanath by Max Thomson. Image © Max Thomson.

The move to an outdoors setting started gradually after the Second World War, with shoots occasionally taking place outside in gardens or at the beach. But the photos kept their formal style until the rise of a youth culture swept away the traditional expectations of a fashion photograph.

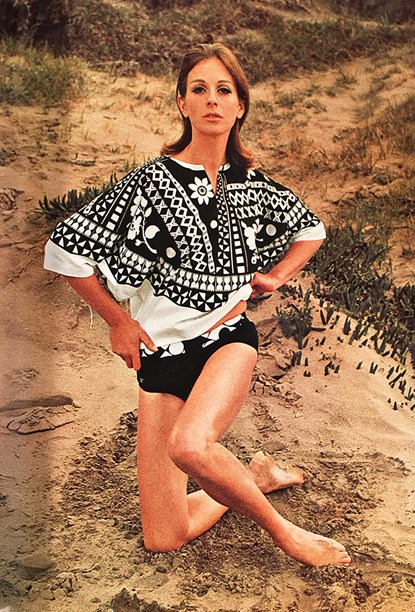

Photograph by Michael Gillies for Babs Radon, 1963. Image © Barbara Herrick.

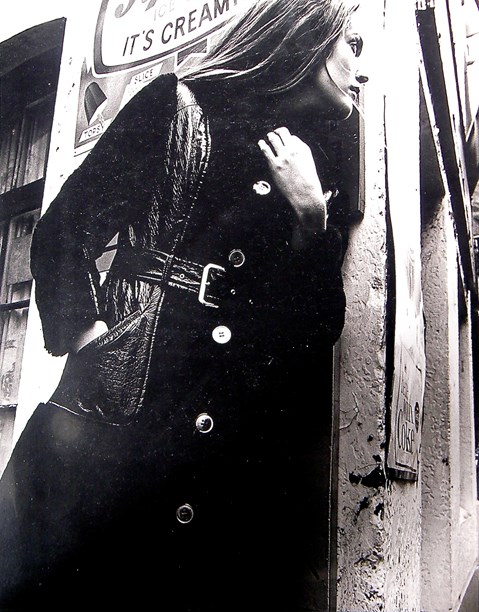

Led by a group of young London superstar photographers, 1960s fashion imagery positioned fashion models in stark and sometimes gritty urban environments, often adopting angular and adventurous poses.

Many New Zealanders were crossing the world to experience Swinging London for themselves. Christchurch photographer Euan Sarginson arrived home in the late 1960s totally besotted with all things British. He set up a studio in his home town where his good friend Barbara Lee was launching her own fashion label and retail outlet, Granny’s Boutique. With Paula Ryan modelling Barbara's designs, they presented their interpretation of the exciting and controversial new fashion trends that were exploding in London.

Photograph by Euan Sarginson for Barbara Lee. Image © Alice Sarginson.

A change in fashion photography in New Zealand is exemplified in Playdate. This new style of lifestyle magazine pitched to the engaged youth audience - it covered music, movies, eating out and of course what to wear when participating in these activities.

Playdate photoshoots took place on the street or in workrooms and coffee bars. Instead of relying on formal studio photographers, editor Des Dubbelt employed photography students from Elam Art School and photographers such as Roger Donaldson and Max Thomson, whose photos had the desired aesthetic.

Photograph by Roger Donaldson for Playdate magazine, May 1970. Copyright owner unknown.

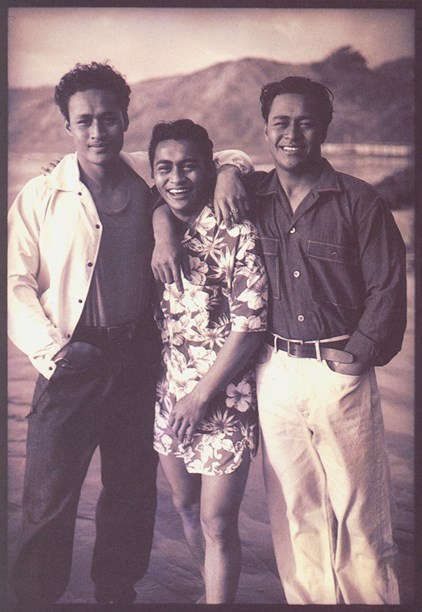

From the 1970s, emerging urban lifestyle magazines were changing how we saw ourselves - rejecting the airbrushed perfection of glossy magazines. This shift reached a critical point in the 1980s when photographers such as Kerry Brown began presenting alternative types of beauty and vitality. Through his use of real people of every colour and age as models in his fashion shoots, Kerry held up a mirror to the people of the city.

Kerry was covering the music scene for Rip It Up magazine when a chance encounter while hitch-hiking changed the course of his photography career. His driver that day happened to be Max Thomson and a week later, Kerry was working as Max’s assistant. When Max Thomson, Rip It Up editor Murray Cammick and fashion designer Ngila Dickson launched New Zealand’s first free fashion magazine, ChaCha, in 1983, Kerry came on board as photographer. His photos for the magazine, and the commercial work that stemmed from it, initiated an important shift in the evolution of the New Zealand fashion scene.

Photograph by Kerry Brown for ChaCha magazine. Image © ChaCha magazine and Kerry Brown.

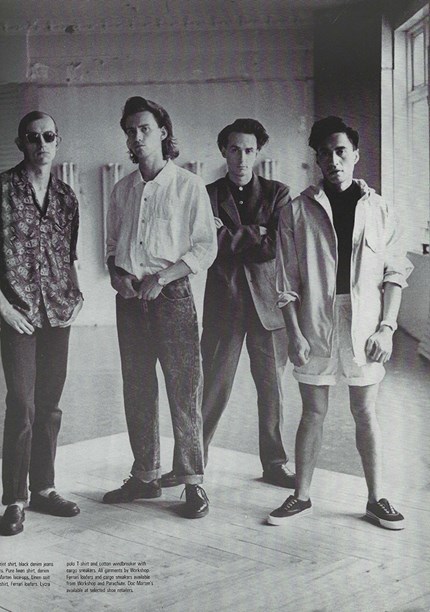

Shooting fashion campaigns for the "new guard in fashion" - Workshop Clothing, Street Life, Equipment Clothing, Standard Issue and Zambesi - Kerry was making images that had never been seen in our fashion magazines. "No one had really done campaigns like that before here," he says. "We brought in fresh faces, kids from the street, from Polynesia, beautiful faces that reflected the multicultural society. Until then, it was really white."

Photograph by Kerry Brown for Workshop. Image © Kerry Brown.

A major factor in this development was his wife Rosanna Raymond who he describes as a fashion activist, a model, artist and stylist. Rosanna played a key role in focusing attention on New Zealand’s Pacific Islander community and integrating them into the fashion world.

Marissa Findlay began photographing for her parents' label, Zambesi, when she was just a teenager. Like Kerry, her images stood out as being edgier compared to the glamorous style that dominated at the time. "Some of my first published work was in Pavement magazine," she recalls. "The art director, Glenn Hunt, helped me to nurture a more cinematic style of photography. He was fantastic at editing my work and finding the edgier and grittier images in the roll to publish - those in-between moments that stand out in my work today."

Photograph by Marissa Findlay for Zambesi, 2016. Image © Marissa Findlay.

Many of Marissa’s photos are taken on the street as she feels it adds character to the image. "It can create a much deeper narrative. I love that it creates for me a scene in which I can act almost like a voyeur, capturing those in between moments of a model in every day activities, it creates that cinematic style that's become such a huge part of my body of work."

Empty landscapes

With landscape as the background to fashion photography, we can compete on the international stage while retaining a look that is distinctly ours.

Technical developments of portability in cameras and sensitivity in film freed up photographers to move out of their studios. The great outdoors provided a new stage for our fashion photography. With West Coast beaches, white sandy bays or empty paddocks in the background, a fashion photograph could portray a fantasy as something attainable, and recognisable, to the New Zealand audience.

Photograph by Phil Fogle of a dress by Susan Holmes. Image © Phil Fogle.

Editorial imagery has increasingly been shot on location and using natural light. While this propensity to shoot outside has at times been slated as lazy, in fact New Zealand’s harsh and changeable light makes this far from an easy option.

When he moved to Sydney in 1990, Monty Adams found himself without the luxury of his polytech studio. He devoured fashion magazines and learnt new techniques for shooting in natural daylight, techniques that have since become a signature of his photographic style.

Photograph by Monty Adams of Rachel Hunter. Image © Monty Adams.

Craig Owen's use of the raw New Zealand landscape always captured attention as he would juxtapose beautiful, often feminine, garments against settings that could be brutal and confronting. In 2011 Craig reflected that it was the lack of "flashy" sets that led to a tendency for local photographers to rely on the landscape as a key part of the story. Without the budgets to work with that are typical in other parts of the world, creating a unique setting relied on what Craig described as "Kiwi ingenuity". "I do love shooting on location because that is something that really affects my work, in the sense that the model and the location are the key ingredients to making a story work. I love when things come together, and the location has caused the story to happen."

Photograph by Craig Owen. Image © Craig Owen Estate.

Photographers Karen Inderbitzen-Waller and Delphine Avril Plaqueel work almost exclusively outdoors and while their images are deliberately constructed, the wash of natural light makes them seem artless and fresh.

Photographs by Karen Inderbitzen-Waller and Delphine Avril Planqueel. Image © Karen Inderbitzen-Waller and Delphine Avril Planqueel.

Karen and Delphine often photograph in city spaces with concrete buildings and streets in the background. But in other photos, blue/grey seas or endless fields provide an almost melancholy setting.

Fashioning fiction

The setting may add an element of story to an image, but a stylist can turn a photo of a garment into a heavily layered narrative.

Photograph by Monty Adams for Simply You magazine. Image © Monty Adams.

Although most of his photographs were taken in the studio, Clifton Firth set up in Auckland's Occidental Hotel for a shoot in the late 1930s. The series is unusual for the era when most fashion photographs were set up to show the clothes, and an exterior location was full of distractions.

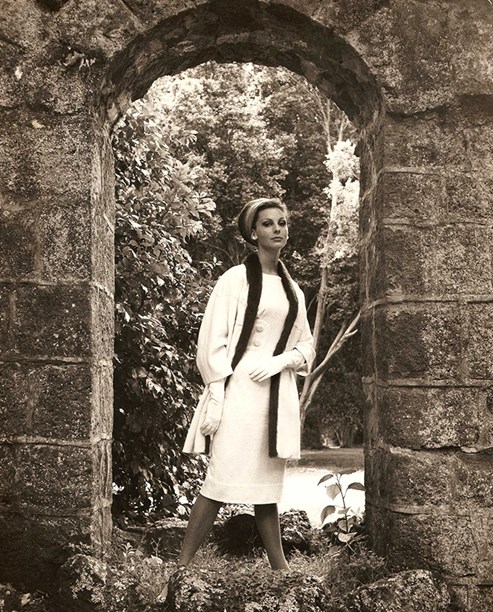

Michael Gillies, who photographed for Vogue New Zealand in the 1950s and 1960s, liked to create the mood and a context for his images. He stood out, says former fashion editor Michal McKay, because he sought to truly understand the clothes he saw through his lens. "He interpreted clothes, and his images would depend entirely on them. We’d talk about what the mood of the clothes were, whether they were formal, or informal, whether they were sporty or whatever, and he would reflect that in the shoot."

Photograph by Michael Gillies for New Zealand Vogue, Summer 1965. Image © The Condé Nast Publications Ltd.

But by the 1990s, the concept of capturing the "mood of the clothes" had expanded and the fashion photography genre was dominated by highly styled narrative editorials.

Magazines were well suited to this style of photography with a sequence of pictures arranged to tell a story. While the brand and designer names were important features, the actual clothes played a secondary role. They were just one of the players in creating a scenario designed to entice an audience wanting to buy into the fantasy of a particular lifestyle.

This style of fashion photography was most successful when it was aimed at a specific audience, something that worked well for magazines of the era, such as Pavement and Pulp, which were targeting a youthful local market.

Photograph by Craig Owen for Pavement magazine, October/November 1997. Image © Pavement magazine and Craig Owen Estate.

The first issue of Pavement magazine was published in 1993. With Barney McDonald as editor and Glenn Hunt as art director, the magazine provided an outlet for a new generation of photographers including Karen Inderbitzen-Waller, Regan Cameron and Marissa Findlay. One of Pavement’s most prolific photographers was Derek Henderson. His narrative style situated the garments in familiar settings.

Derek Henderson for Pavement magazine, June/July 2001. Image © Pavement magazine and Derek Henderson.

At a time when New Zealand fashion was being noticed by an international market, this narrative style of photography added a new dimension to ‘the New Zealand style’.

Early in his career, Craig Owen also photographed for Pavement magazine. In an interview in 2011 he admitted that when he first started out, capturing a detailed photograph of the clothes wasn’t a priority. "When I first started shooting, the clothes were the last thing that mattered to me … Even if the clothes were blurry or there was not enough light on them, if the picture was great then that was all that mattered."

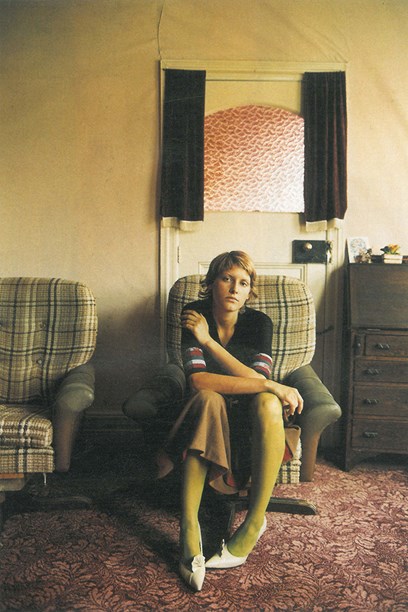

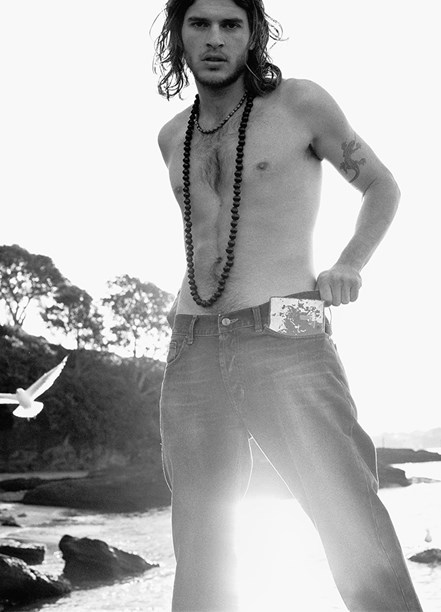

Stephen Tilley was working in London during the 1990s, and on his return to New Zealand in 2000 he shot some campaigns for NOM*d, as well as editorials for Pavement and Fashion Quarterly. Despite the strong appeal to fantasy in fashion photography, Stephen says he likes to tell a story that is honest. His journalistic style reflects his fascination with people and their most raw and real moments.

Photographs by Stephen Tilley. Image © Stephen Tilley.

Chris Sisarich worked as an assistant for Craig Owen and Monty Adams while he was studying photography, "completely obsessed with becoming the world’s greatest fashion photographer". In the late 1990s and early 2000s he gave the genre his full attention with few New Zealand magazine titles left off his portfolio. Although he now works as a commercial photographer, Chris describes fashion photography as the perfect coming together of freedom and creativity. "It was a dance between me and the model and I loved it. It was that interaction between my vision and personal creativity and the model’s personality and what they brought to it. Then the clothes became the character. Those three things determined the story. I loved those three things and I still love them when I photograph now."

Photograph by Chris Sisarich for Fashion Quarterly magazine. Image © Chris Sisarich.

The rise of internationalism and the internet has meant that New Zealand magazines are being read online all over the world. But highly stylised and symbolic narratives do not necessarily resonate with a global audience.

Image making

Fashion photography is very much a construct that can be approached from many angles.

When looking at a fashion photograph it is important to consider the intention of the image. The medium is an entity formed from an intersection of the photographs themselves, their content and supporting text, the publications they appear in and the reception of that photography. Over time the garments have moved from centre stage to a supporting role as the sophistication of audiences required more complex messages.

Photographs by Euan Sarginson (left) and Marissa Findlay (right). Copyright © Alice Sarginson and Marissa Findlay.

Only the catalogue remains as a form of documentation of the garment. Commissioned by the designer, these photos focus on the object, utilising lighting and poses that present the entire garment in splendid clarity.

Catalogue photograph by Stephen Tilley for Barkers. Image © Stephen Tilley.

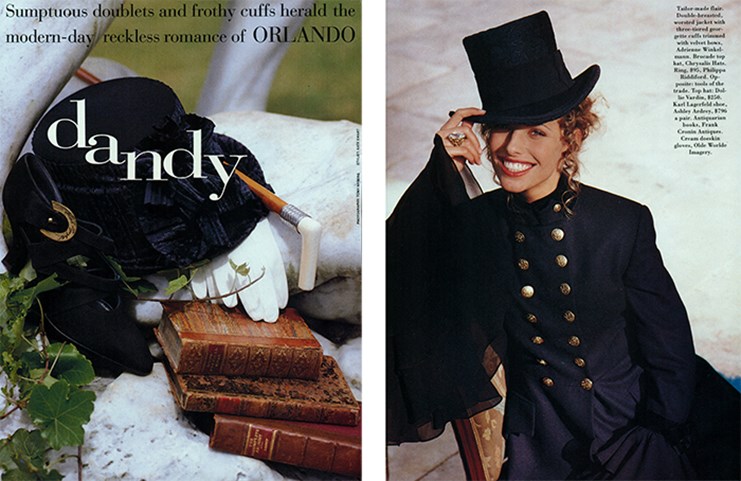

Rather than recording the details of a garment or pushing the brand of a designer, magazine editorial photography sells the dream of the day. The images are highly evocative references to people, places, social, technological, environmental and industrial change over time, which expose the shifts in our actual and aspirational identity.

Editorial from Fashion Quarterly magazine, Autumn 1994.

The campaign photograph, in contrast to the catalogue or editorial image, is commissioned by the designer or the brand to create images that make a statement about their current aesthetic. While they will choose a photographer capable of communicating that vision, the vision remains their own.

Photograph by Kerry Brown for Workshop. Image © Kerry Brown.

In response to the current social fascination with real people and real lives, brands are creating behind the scenes videos of photoshoots. Suddenly the photographer is in the spotlight and his or her role in the construction of an image is on display.

Barkers summer 14/15 Behind the scenes video.

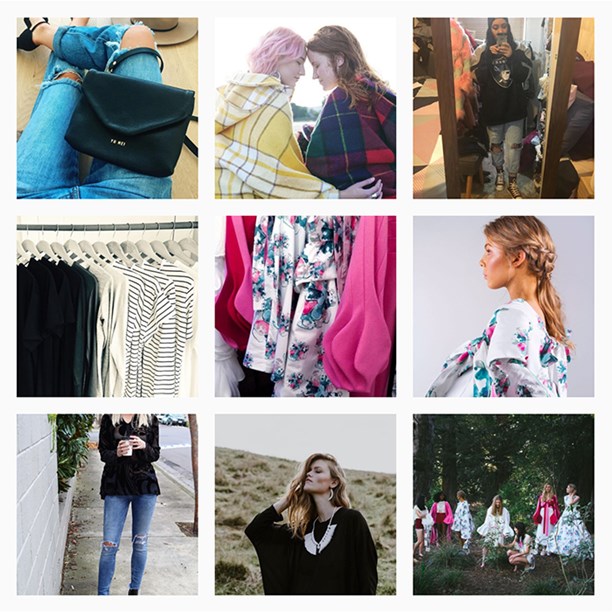

But even the behind the scenes images depict a fantasy. As it becomes the norm to share a stylised perspective of your own life in fashion, audiences are bombarded with constant images. The professional photographs of your favourite fashion labels appear in the same social feed as photographs of your well-dressed friends. Today it is the global glut of images that presents a challenge for photographers. The challenge is how to stand out.

Search results for the hashtag #nzfashion on Instagram, June 2017.

Viewing fashion photography as "a bare canvas for any kind of idea or expression" meant that Adam Custins was very open to learning and experimentation. His style underwent a complete change in 2010. Instead of continuing to use artificial lighting, large crews and intensive styling, he stripped everything right back to basics, finding the aesthetic that defines his work today. "I felt that if I was going to really progress as a photographer, I needed to virtually relearn how to make powerful images with the least amount of stuff," he says.

Specialising in Polaroid film gives Adam’s images a dreamy, otherworldly feel. Colours saturate oddly on the instant film, which is often long expired before Adam brings it back to life, and the natural light gives his subjects softened edges and unexpected contrasts. Adam’s work in the exhibition, Hyperreal, in March 2017 explored the way fashion can become a symbol of partisan politics. His photo of a pair of white New Balance shoes refers to the protests by owners of these shoes when a board member endorsed Donald Trump as an election candidate. The photo was shot on large format instant film, referencing the nostalgia of both the Polaroid film and the idea of ‘Make America Great Again’.

Photograph by Adam Custins for the Hyperreal exhibition. Image © Adam Custins.

Hyperreal was organised by the Advertising and Illustrative Photographers Association. The current executive director and fashion photographer, Aaron K, is a passionate supporter of artists rights, especially in light of the increasing impact of global corporations on local economy. He describes a working landscape that is becoming increasingly isolated through newer technologies. "Before digital photography came along, the labs were a real hub for interaction – inevitably you’d bump into another photographer."

Photograph by Aaron K for the Hyperreal exhibition. Image © Aaron K.

As a group exhibition, Hyperreal was a response to this isolation. The title alludes to the fact that the imagery produced for fashion magazines and advertising campaigns is not a true representation of reality, but is distorted or exaggerated. This was described in the exhibition catalogue: "As such fashion photography is a form of fiction where the photographer assumes the role of director or author."

However, as with all forms of artistic expression, fashion photography is subjective. Whatever the photographer’s objective, the viewer will inevitably filter the images through their own life experiences and personal tastes.

Text by Kelly Dix. Banner image by Clifton Firth taken at the Occidental Hotel in Auckland, 1939. Contact Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries, 34-Z276 for copyright details.

Last published July 2017.