Stories

Divine Inspiration

Autumn/Winter 1994

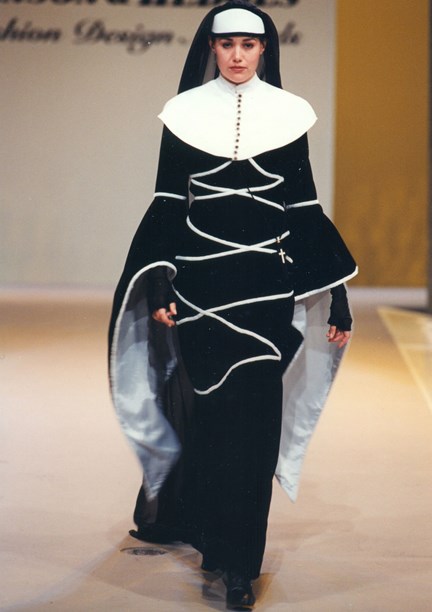

"Although it may not be the answer to every woman’s prayer, ecclesiastical dressing is one of this winter’s key looks," noted Maysie Bestall-Cohen when describing Beatrice Galway’s entry in the 1994 Benson & Hedges Fashion Design Awards. A black velvet adaptation of a nun’s habit, with flaring medieval sleeves, white velvet ribbon crisscrossed around the body and an improvised wimple, the design was a clever play on the new 'chaste chic'.

It all started when sacred imagery pervaded the international runways at the 1993 international Autumn/Winter collections. Designers such as Chanel, Donna Karan, Adrienne Vittadini, Christian Dior, Ann Demeulemeester, Moschino, Jean Paul Gaultier and Prada all showed clothes which made a clear reference to religion. Their evocations of Catholic, Buddhist, Anglican and Hassidic ritual garb included priest-like cloaks, penitent robes and monastic dresses.

"It seems nothing is sacred which may well lead even those with a blind faith in fashion designers to wonder, why now?" commented American Bazaar. "Is all this an act of contrition after the excesses of the 80s?"

The ecclesiastical influence which infiltrated the New Zealand 1994 Autumn/Winter collections was more simplistic, drawing mainly on the contents of a cleric’s closet for inspiration. The black cassock and the white surplice, traditional vestments worn by the clergy and choirboys, were interpreted variously as dresses, coats, shirts and skirts. Everything was long, penitent in tone, and covered the body from neck to ankle.

Commercial imperatives prevented local designers from taking the same liberties with religious-inspired dressing as their overseas counterparts. They confined themselves to producing sober, well-cut garments with street appeal and remained faithful to a colour theme of all black or a combination of black and white. There were a few exceptions, such as Chrissy R’s monk’s-hood sweater dresses in Franciscan brown and Calliope Road’s long wool cardigan coats in a shade resembling watered-down Communion wine.

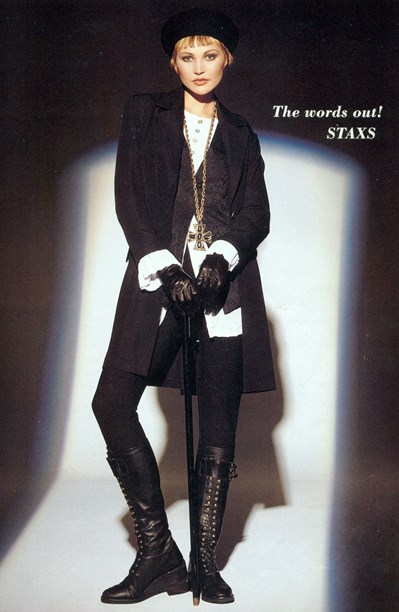

Ecclesiastical-inspired separates from Staxs 1994 winter range.

Mid-calf length white shirts designed by Ashley Fogel, although less voluminous and narrower in the sleeve than a surplice, gave a good imitation of the real thing when worn over wide-legged black pants.

The cleric’s coat, invariably long, lean and black, differed in detail from label to label – stand-up collars at Country Road, velvet collars at Keith Matheson, a flash of white cuff at Miss Deb, pearl-centred gilt buttons at Thornton Hall, big black buttons at Rosaria Hall.

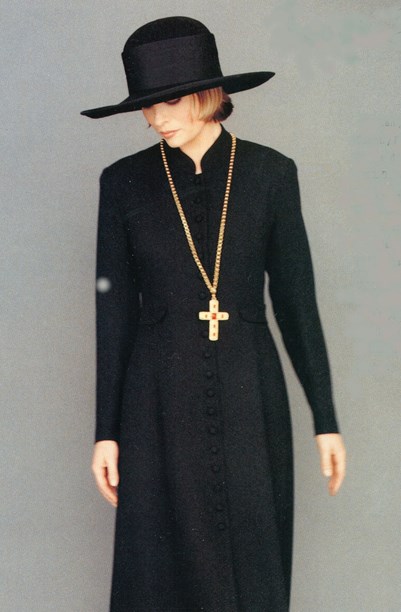

Ankle-length cleric’s coat from Keith Matheson 1994 winter collection features tiny self-covered buttons and a stand-up collar.

To relieve the austerity of the all black dress, Barbara Lee added a crisp white collar and cuffs, as did Keith Matheson, the difference being that his collar and cuffs were detachable. Preaching bands, short strips of white cloth traditionally attached to a clerical collar were sometimes represented in the form of a floppy white bow.

Another proponent of monastic dressing was knitwear designer Caroline Sills. Fluid and unfussy, her black wool dresses and flared tops softly followed the lines of the body to the waist before drifting downward to swathe the knee or ankle.

Monastic dress in boucle wool by Auckland knitwear designer Caroline Sills.

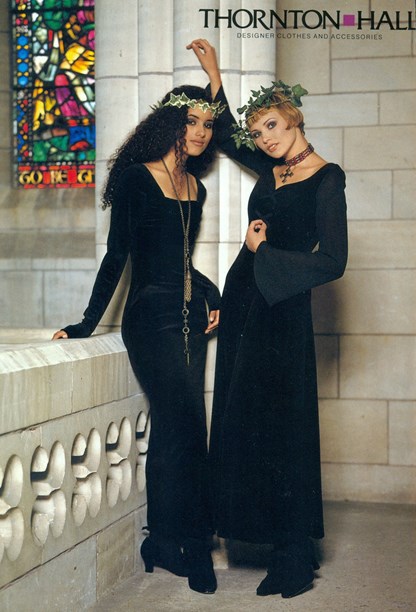

Long black dresses that expressed a less worshipful attitude, such as those with lower necklines from Dreamgirls, Thornton Hall and Expozay, were easily redeemed by embellishing with the costume jewellery item du jour, a crucifix suspended from a long ribbon, cord or chain. The more ornate jewelled versions bore a passing resemblance to those personally designed by Chanel whose long-standing fixation with the cross is often attributed to her having spent her younger years in a convent orphanage where crucifixes would have been a common sight.

Thornton Hall dresses with medieval-style sleeves. Winter collection 1994.

Lisa Hoskin, Penelope Barnhill and Catherine Clifford were among the local jewellery designers to respond to the demand for crosses. They used their ingenuity and expertise to craft unique and highly decorative pieces. Crystals, jets and pearls were incorporated in their designs, as well as silver, brushed gilt and other metals.

Bejewelled, wooden, brass, silver or gold, crosses came in myriad forms. Fashion Quarterly, Winter 1994.

There were those who regarded wearing a cross for adornment as disrespectful but, unlike Madonna, who irreverently appropriated the cross as part of her costume in the 1980s, in 1994 there was no sacrilegious intent. Although it was customary to wear a cross as one would an ordinary pendant necklace, it was sometimes worn diagonally across the body.

The modest crucifix worn with Beatrice Galway’s nun-inspired outfit in the 1994 Benson & Hedges Fashion Design Awards originally belonged to a nun at the Sisters of Mercy Convent in Auckland. It had been gifted to the noted opera singer Mina Foley who later gave it to Beatrice’s mother.

Beatrice says of her Highly Commended design: "The inspiration started with my early childhood memories of attending a Catholic primary school. The older nuns in the adjoining convent wore traditional habits, an image that startled me at first but piqued my interest as time went on." The ecclesiastical tie-in with fashion in 1994 rekindled those memories for Beatrice who reimagined the nun’s habit as a statement of "confined sensuality, designed to shock and enchant."

Beatrice Galway’s theatricalised version of a nun’s habit with a chiffon train was Highly Commended in the Avant Garde category in the 1994 Benson & Hedges Fashion Design Awards.

For all the talk of propriety and less excess, fashion’s rejection of worldly indulgence didn’t last long. By summer 1994, colour had returned, the body came out of hiding and short skirts were back with a vengeance.

Devotional dressing and crucifixes made a brief reappearance in 2001. At the first New Zealand Fashion Week, models wearing monk-style wraps and hoods by Mosaic (a High Society label) glided down the runway, clutching sizeable diamante crosses. In her Czarina collection that winter, Robin Jones (RJC) referenced the Russian Orthodox church by attaching a solitary diamante cross to the front of t-shirts and delicious tulle tops. Personal statements from individual designers, rather than a fashion trend, these were but an echo of Winter 1994 when the craze for ecclesiastical fashion was at its peak.

Text by Cecilie Geary.

Last published April 2018.