Stories

Adornment in Moana Currents

The default position of the New Zealand Fashion Museum asserts that what we wear makes a significant contribution to our ongoing cultural conversations and our primary focus has been clothing. The framing of Moana Currents: Dressing Aotearoa Now, however, invites us to consider all elements of being 'properly dressed' including accessories, body modification and adornment.

Across the moana leaf skirts, plain barkcloth, woven matting and cloth provided the materials that fulfilled people's need to be covered for modesty and for warmth. But early European encounters documented that there was a difference in the clothing worn by people of status and by commoners; distinguished by attributes like the quality and rarity of the materials that were used and the application of sophisticated and intricate patterning. The wearing of head, neck, waist and arm adornments was also recorded; all are strictly non-utilitarian additions. Clearly decoration and adornment are signifiers of something; they are an aesthetic expression and/or a social one.

The materials and forms that were used reflect their own resources. Ephemeral materials like locally grown sweet-scented or brightly coloured flowers, foliage, fruit, bark and fibres were used in the form of garlands worn around the head, waist or neck. Often used in greeting, to honour someone or to recognise achievement, the encircling form of the lei signals inclusiveness. Adornment made from more durable materials like feathers, hair, shells and stone act as a marker of enduring connections and values which are often passed on through generations and sometimes are even given their own name. The materials used might have status because of their rarity, being limited in supply like the tiny red feathers from the Hawai'ian i'iwi bird that were used to make the chiefly cloaks and helmets in Hawai'i or because they were materials that could only be obtainable through inter-island trade and exchange.

Kalani'ōpu'u's sacred cloak gifted to Captain Cook in 1779.' Ahu 'ula (feathered cloak), 1700s, Hawaii, maker unknown. Gift of Lord St Oswald, 1912. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Te Papa (FE000327)

Form, material choice and values however are not static or immune to outside influences. Trying to fix a particular cultural practice as 'traditional' comes from old evolutionist thinking where traditional is synonymous with primitive and we in the west, have evolved to more advanced practices. In truth all cultures are dynamic, adopting and adapting new technology, materials, and ideas where that suits their purposes. Archeological evidence from across the moana documents the many developments and changes over thousands of years.

The arrival of Europeans in the moana however brought with it a huge incremental shift in available materials and technologies. Metal tools for agriculture, fishing, stone and woodworking plus the introduction of manufactured goods such as cloth and fine needlework skills were new resources that were readily assimilated by Moana people into their lives. Inevitably European contact impacted to change the value and meaning of existing cultural practices while at the same time adding new symbols of identity and status to their repertoire.

A short story of a singular object that is both adornment and cultural signifier, the hei tiki, will serve here to illustrate some of the processes of change and how time, circumstances, intent and reception all impact on the effective power and cultural value inherent in an object.

Variants of the word 'tiki' are common in the languages of the islands and refer to a carved humanoid figure with its origins in the creation mythologies of the Moana. It is said to represent the original human, the progenitor, which links it inextricably with fertility, with life (some see it as an embryo) and the inevitability of death thereby connecting it to the ancestors and imbuing it with spiritual value. The hei (hung around the neck) tiki is unique to Aotearoa and arguably the most archetypical Māori artifact. European records of early encounters document the hei tiki being worn by both men and women and a sketch of a Māori chief by artist Sydney Parkinson who accompanied Cook in 1769 shows a man with facial tā moko (tattoo), his hair in a top knot dressed with a comb and feathers and wearing a kaitaka (fine woven flax cloak), pounamu earring and a hei tiki on woven cord.

Portrait of a Māori man by Sydney Parkinson, October 1769. Image from Alexander Turnbull Library, ref. Publ-0037-16.

Early hei tiki were commonly made from local nephrite. Because the first settlers who arrived in Aotearoa from the islands to the north-east brought stone-working technology they were able to fashion this very hard stone into tools, weapons and objects of adornment. Found only in some rivers of the South Island, the stone was given the name pounamu and lent the South Island its Indigenous name, Te Wai Pounamu, the water of greenstone, articulating its cultural and economic significance for Māori.

The European migrants who arrived some 500 years later brought metal tools and weapons quickly usurping pounamu from its utilitarian function, but not from its decorative use, which in fact increased as an unintended consequence. Hei tiki now became essential props in the conventional representation of Māori in colonial portraiture and photography, so paradoxically while they became physically bigger objects, their spiritual value was diminished.

Portrait of guide Susan from Rotorua, taken in about 1905 by Josiah Martin. Image from Congress collection, LC-USZ62-112688.

For Pākehā hei tiki became decorative markers of settler nationalism and permeated the dress code. The society pages of the day described in detail what people wore. One such in 1907 reports that Katherine Mansfield (then Beauchamp) wore "a black crepe-de-chine dress, her sole ornament being a large ivory(sic) tiki". Now housed in the Katherine Mansfield Birthplace Collection this hei tiki was gifted with a note from her eldest sister Vera who wrote, "This maori tiki was shared and worn by me and my sister K.M. when as school girls in LONDON, we wished to be identified as New Zealanders."

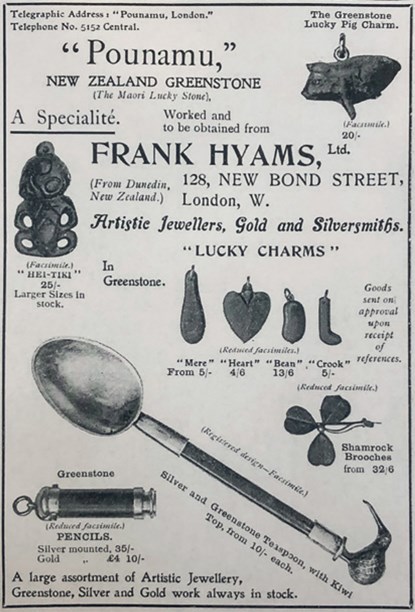

Appreciation by the colonists of its beauty and uniqueness created a commercial market for greenstone jewellery. Māori, who had always demonstrated a willingness and ability to meet new markets for goods and services, carved hei tiki as well as fashionable Western forms for sale. The now defunct adzes and patu (clubs) were transformed into desirable objects of adornment. Hei tiki and other ‘amulets’ carved from pounamu became fashionable items in London where orientalism, primitivism, and aestheticism were in vogue, and in 1903 Dunedin jeweller Frank Hyams was selling 'Pounamu, New Zealand Greenstone, Lucky Charms' at 128 Bond Street, London.

Frank Hyams was a Dunedin jeweller, silversmith and watchmaker with a stores in New Zealand and London in the early 1900s. He was a leading manufacturer and dealer of New Zealand greenstone at the time and had the stone shaped and set to meet the fashion tastes of the day. This 1903 Frank Hyams promotion is the earliest known British advertisement for commercially produced hei tiki. Image is sourced from The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Vol 1, No 1 (March 1903).

But as is the way with fashion, the trend had its moment and was gone. The reduced market for carved pounamu threatened to undermine the maintenance of stone carving skills and the preservation of the associated cultural values. To counter this and the decline in other art practices, visionary Māori politician Āpirana Ngata intervened and in 1926 was instrumental in establishing the New Zealand Maori Arts and Crafts Institute in Rotorua (a tourist destination since the 1880s). They taught carving in wood, stone, and bone with some of what was produced aimed specifically at the tourist market for whom hei tiki in pounamu was quintessentially representative of Aotearoa. Indeed, it became so emblematic that in the 1960s the national airline, TEAL, was manufacturing green plastic hei tiki as a giveaway for all their passengers.

Plastic hei tiki souvenir from TEAL airline. Courtesy of the Museum of Transport and Technology.

All this was set to change in the 1970s, a time of social activism internationally and in Aotearoa where it marked the beginnings of a Māori cultural renaissance that witnessed historic land claims addressed through the Waitangi Tribunal, which was established in 1975, the introduction of Te Kōhanga Reo (Māori language nests) in 1982, and in 1987 Te Reo gained legal status as one of the two official languages of Aotearoa. Renewed attention to spiritual values moved Māori cultural objects and practices into a contested zone effectively putting hei tiki outside the ambit of Pākehā makers and wearers.

Contestation around the use of hei tiki is ongoing with claims of appropriation by Māori activists and staunch opposition to any reinterpretation of the conventional form expressed by Māori traditionalists. Nonetheless, hei tiki is being reclaimed. Its form is being revised and reinterpreted, and it is being carved and created in a wide range of new materials.

For Moana Currents we have chosen a hei tiki which has been 3D printed in polyamide by visual artist Kereama Taepa. His use of contemporary materials and technology contributes to the evolution of Māori cultural forms and motifs making them relevant and, in this case, wearable and affordable.

3D printed polyamide tiki by visual artist Kereama Taepa.

We have also included Neil Adcock’s 'Dancing Tiki', made in pounamu and silver, to illustrate that hei tiki can even be delivered and worn with good humour. But hei tiki continues to speak a complex and challenging language, and negotiating its place in the lexicon of Aotearoa symbols remains a finely nuanced dance between heritage and modernity.

Treading that fine line has been challenging for contemporary jeweller looking for ways to express what it means to identify as citizens of these islands in Te Moana nui a Kiwa. In the 1970s and 80s, a new understanding of our identity in Aotearoa was developing, led by the successes of the Māori cultural renaissance and its statutory recognition, as noted in the hei tiki story. Aotearoa was also coalescing around our independent anti-nuclear stance as articulated by Prime Minister David Lange at the Oxford Union Debate in 1985. Protest against nuclear testing in the Pacific region since the mid-1960s was given renewed traction when the French government bombed the Greenpeace ship Rainbow Warrior in Auckland harbour that same year. We were waking to the need to re-evaluate our traditional allegiances and to reposition ourselves in the world drawing strength from what was unique to us. For contemporary jewellers in Aotearoa that meant a move away from European traditions and precious materials to using local materials and moana making traditions, imbuing them with value by honouring the forces of nature that created them, making them a powerful symbol of the wearer's identity, not symbols of economic status.

Alan Preston, who in 1974 initiated the establishment of Fingers, the contemporary jewellers collective in Auckland, shared his 'Ulabanana' necklace. Made out of banana seeds and strung onto strands of dyed vau (hibiscus fibre) some of the seeds have been painted red. Referencing the Samoan ulafala, the pandanus key necklace worn by high ranking chiefs, Alan's interventions have elevated the value of the mundane seeds.

Alan Preston's 'Ulabanana' necklace. Photo by Edith Amituanai, model Hezekiah James Setu.

Neil Adcock's articulated 'Dancing Tiki' is made from different varieties of pounamu in colours from pale jade to peppermint hues which have been thinly sliced and polished allowing light to pass through and illuminate the natural beauty of the material. The use of kauri copal gum for a second pendant also showcases its depth and clarity, with swirls of nebulae-like patterns and air bubbles encapsulated in its formation tens of thousands of years ago connecting the wearer as a guardian to the ancient forests of Aotearoa. The third piece, an unadorned mother of pearl shell that is worn as a neckpiece, allows nature to speak for itself. In its simplicity the shell’s own natural beauty and iridescent palette of creamy white, silver and pink is valorised.

Three pieces by Neil Adcock.

These are examples of transformation but also of continuity. And it is the threads of continuity that we are looking to draw out of our chosen objects. Seeds, shells, stone and wood, all feature as adornments in history and remain part of the dialogue in the 21st-century. Zelda Murray engages in that conversation with her hand-carved wood earring which nods to the heritage of carved wood found in Polynesian handicrafts, its smooth shape mimicking that of a Samoan pate (drum) and is hung off a contrasting Perspex teardrop. Ephemeral materials such as flora are replaced by strings of glass beads that are shaped into the outline of petals that hang like pendulous flowers from your ears or pinned to your dress. Porcelain discs with the texture of seashells are caught in a silver clasp and worn as earrings, marrying motifs from the moana with western materials and technologies.

Three pieces by Zelda Murray.

The use of materials with a prior history encapsulates the notion of continuity and circularity, thinking about the future and being connected to the past. Indeed, the survival of cultures depends on this dynamic of bringing old knowledge and experience to new materials and technologies to create contemporary meaning. Fran Allison has collected discarded crocheted doilies from op shops for her 'Doily Daisy Chain'. Her careful attention to them, turning each into a flower for her daisy chain, honours the hours of labour and skill that went into their original creation by reinventing them into a moana lei or garland. Attention and care also guide the transformation of a discarded t-shirt into Bead necklace from a t-shirt.

This seven meter continuous strand of cloth beads cut from a single t-shirt elicits memories of the history of trade beads and the possibility of making a fair trade today, "Give me a t-shirt and a koha and I’ll give you a bead necklace" says Fran.

Bead necklace from a t-shirt and Doily Daisy Chain by Fran Allison. Photos by Allan McDonald and Mara Sommer, models Frances Coulibaly and Layla Dole.

For all these makers adornment is not only an aesthetic expression but also a social one.

Their exploration and the work that emerges from it is inextricably linked to their geography as citizens of these islands in Te Moana nui a Kiwa. They invite us to take our bearings and express that relationship through what we choose to wear.

Text by Doris de Pont. Banner image by Sam Hartnett, courtesy of Te Uru.

Published October 2019.